This brief illustrated review of 200+ years of Minnesota languages and language teaching reminds us to champion multilingualism and to hold true to our history while we influence our future. The article is based on Elaine Tarone’s plenary address at the first Minnesota English Learner Education (MELEd) Conference, Nov. 15, 2014.

In 1979 when I first moved to Minnesota to teach in the M.A. ESL program at the University of Minnesota, I had the mistaken impression that this was a fairly monolingual and monocultural place – certainly much more so than Seattle, where I had been living. My impression was reinforced by cartoons by Richard Guindon published in the Minneapolis Star Tribune in 1979 for newcomers to Minnesota. Those cartoons made it clear, for example, that an ethnic restaurant was a place with spaghetti; a “mixed marriage” was when Norwegian and Swedish Lutherans got married; and an “ethnic” was someone with brown hair and brown eyes. I might have been forgiven for thinking that everyone in Minnesota except the international students at the university was a monolingual English speaker … and always had been. But I would have been wrong. Here is what I’ve learned since about multilingualism and English learner education in Minnesota.

Minnesota Languages until the Louisiana Purchase

It turns out that lots of indigenous languages were spoken in Minnesota for thousands of years. By 1500 most of the Native Americans living in what is now Minnesota spoke Dakota.

But in 1500 the Anishinaabe (also Ojibwe, or Chippewa) people migrated from the east and flooded into the north part of what is now Minnesota; there was conflict and the Dakota people moved to the south. Large areas including what is now the West Side of St. Paul were reserved for Dakota people until the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux in 1851. Imagine: West St Paul was Dakota-speaking until 1851!

The 1600s also saw the introduction of a European language. French voyageurs were pursuing the fur trade, and the French, Ojibwe and Dakota languages came into contact with one another.

In 1680 French explorers, including Father (Père) Hennepin, were taken by an Ojibwe group to the only natural waterfall on the Mississippi River, a place the Ojibwe called owahmena. The French decided to call the falls Chutes de San Antoine; the name later became St Anthony Falls. The place names of Minnesota still reflect the linguistic history of the state: French names include Hennepin Street, the St. Croix River, Lac qui Parle County, Duluth, and my favorite, the redundant Mille Lacs Lake (“One thousand lakes lake”). Dakota names are Waconia, Winona, Wabasha, Kandiyohi, Mankato (a misspelling of Mahkota “blue earth”), Shakopee and of course, the very name of our state, Minnesota (from Mni Sota). Ojibwe place names include Anoka, Bemidji, Chisago, Mahnomen and Wayzata.

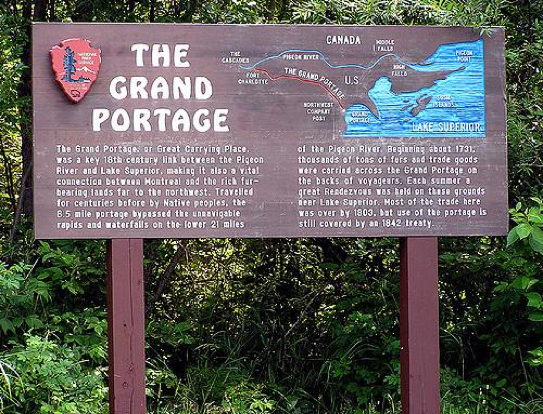

In 1731 a French speaker, Pierre de Verendrye, was the first European to traverse the nine-mile “great carrying place” in the northern part of what is now Minnesota; other French speaking voyageurs followed him on this passage, calling it the Grand Portage trail. But in 1763 after the French and Indian War, the British took over the trail as a fur-trading route. By 1783, the English-speaking British Northwest Company was well established on the Grand Portage Trail (although the French voyageurs continued to work with them) (Lass, 1998: 64-65, 72-73).

English Speakers Settle in Minnesota

After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, English-speaking people from the Eastern part of the U.S. moved in to settle the new territory.

As Prof Harold B. Allen’s linguistic geography of the Upper Midwest would later show, settlers tended to move and settle directly west from their original East Coast homes, so that dialect maps looked like roughly horizontal strips across the map. Minnesotan English tends to reflect New England dialects while Iowan English reflects the English dialect originating a bit more to the south in Pennsylvania. Colin Woodard’s book American Nations states that these settlers brought differing cultural values along with their dialects. Woodard says the New Englanders who settled Minnesota valued public education, public libraries, higher education, democracy, and the common good, but also had a deep intolerance of anyone who did not share those values. Those who settled in Iowa were more pragmatic.

In 1819 Fort Snelling was founded by the U.S. federal government, which was worried about British expansion and wanted to extend U.S. jurisdiction. The English-speaking fort was built on a high spot at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers (a place called Bdote by the Dakota) that had been acquired in 1805 by Zebulon Pike by treaty with the Dakota (Lass, 1998: 82-85). Fort Snelling in theory guarded land west of the Mississippi against settlement, but subsequent treaties in 1837 with the Dakota and the Ojibwe did permit settlers east of the Mississippi River (Keillor, 2008: 13). Multilingual squatters – French-, English-, and Dakota-speaking — set up residence all around the fort. Near Fort Snelling, mission schools were established to educate American Indian children who lived in local villages with their families. In 1834, Samuel and Gideon Pond established a mission school for Dakota children who lived with their families in a village located at Lake Calhoun (a lake which they knew by its Dakota name: Bde Maka Ska). The Ponds themselves learned Dakota and devised an alphabet to translate the Bible into Dakota (Clemmons, 2000), but we do not know how much Dakota was spoken in their school.

In 1837, an English speaking Canadian named Peter Garrioch, aged 26, found himself stranded in Minnesota, having missed the last boat down the Mississippi before it iced over for the winter. At the suggestion of Martin McLeod, a trader with the American Fur Co., he agreed to teach in Minnesota’s first public school at Camp Coldwater, which was located northwest of Ft. Snelling, around the present location of the V.A. Hospital. McLeod gave him a contract for 6 months for $50, room and board. This first public school class was very diverse; it consisted of children of English, French, Swiss, Swede, Cree, Ojibwe, Dakota, and African extraction – an early documented case of a multilingual classroom. Garrioch’s attitudes toward young children were negative, and he did not linger in Minnesota after his contract expired and the ice melted (Gunn, 1939).

Settling Saint Paul

In 1838 Pierre “Old Pig’s Eye” Parrant, a sketchy 60-year old one-eyed French-speaking fur trader and bootlegger, staked a claim for a tract of land at Fountain Cave on the east side of the Mississippi River, near the current site of downtown St Paul.

The spring inside the cave was a great source of water for his whiskey still, so he opened a bar there for Ft Snelling soldiers, French Canadians and Dakota alike; the bar and the surrounding community were called “L’Oeil de Cochon” (Pig’s Eye) (Lass 1998: 99). Two years later, in 1840, a 29 year old French-speaking priest, Father Lucian Galtier, built a log church in the area and named it St. Paul (Lass 1998: 100). For several years it wasn’t clear whether the growing town would be called Pig’s Eye or St. Paul. More French speakers settled nearby, along with indigenous people and metis (mixed French/native people). West St Paul was Dakota-speaking; the predominant languages in this little town were French and Dakota.

By the 1840’s the town was increasingly called St. Paul, as it became a more linguistically and culturally diverse river city of immigrants. St. Paul’s Catholic parish held three services in one building: one in French, one in German, and one in English. Swedes settled in “Svenska Dalen,” or Swede Hollow. Lower St Paul was called “Old French Town,” with French Canadian, African American, and Dakota inhabitants.

In 1847 Harriet Bishop, a 30 year old English-speaker from Vermont, a suffragist and temperance advocate with the New Englander’s penchant for intolerance, defied her parents’ advice and traveled west by herself to find adventure. She opened a school in St. Paul, keeping a journal recording her low opinion of the conditions in which she taught. Her first year she described her school as “a mud-walled log hovel covered with bark and chinked with mud” at St. Peter Street and Kellogg Boulevard; her classroom was very dark inside, with small paned windows, and rough planks forming benches for the children, and one chair for the teacher. During her first year in the “hovel,” Harriet taught 7 children, 2 European and the rest meti or Dakota. She spoke only English; her children spoke French and Dakota. Fortunately one meti girl was trilingual in French, Dakota and English, so this girl was tapped to act as a translator. According to Bishop, Dakota women and sometimes men would slip in the door and sit and listen to the lessons, presumably as translated by the young girl.

It was in fact a rough environment for a school. Bishop recorded that the first winter, temperatures dipped below zero, and that on one occasion 50 Dakota men just back from an armed skirmish with Ojibwe to the north stood outside shooting their guns in the air, terrifying the children. However, within two years, by 1849, Bishop was holding class for 40 children in a frame building at the bottom of Jackson St with the help of another woman teacher from the East (Morton, 1947). They were obviously teaching academic content through English to English learners, though of course they, like the Pond brothers and Mr. Garrioch before them, were not trained ESL teachers.

Statehood and Education

In 1849, Minnesota became a U.S. territory; in that year, Martin McLeod, the fur trader who’d paid Garrioch to teach, authored legislation setting up a fund to provide free education to all children in the Minnesota Territory, regardless of race. However, in 1858, nine years later, when the Minnesota Territory became a State, that progressive New England style legislation was to be replaced by a system in which American Indian and African American children began to be educated separately — a sad outcome of Minnesota’s admission to the U.S. as a state (Clemmons 2000).

Before that, in 1851, while Minnesota was still a U.S. territory, the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and other treaties made the Dakota cede large swaths of land to white settlers (see map below).

As a result, just two years after McLeod’s progressive legislation, Dakota settlements were no longer allowed in St. Paul; Dakota people would now be restricted to the banks of the Minnesota River and out-state reservations that would turn out to provide too few resources to support them. In 1855, a small Hochunk (Winnebago) reservation was placed in Long Prairie as a buffer between the Ojibwe to the north and the Dakota to the south. The Arrowhead region of northern Minnesota, where there were Ojibwe settlements, provided more stable sustenance for hunters and gatherers, but, with their territory restricted, the Dakota became dependent on U.S. government food supplies, which were delivered only sporadically. Now that the Dakota people were relocated, speakers of European languages began to move in to the west side of St. Paul, St. Anthony, and Minneapolis. Towns and villages were established across Minnesota, conducting business in a variety of European languages.

In 1854 New Ulm was founded by the German-speaking settlers shown to the left, and soon after, Scandia became a town of Swedish-speakers. In 1854 New Englander John H. Stevens got special permission from Fort Snelling to build a house west of the Mississippi River because his new ferry docked there. Then other English speakers moved in near him, and soon a town was incorporated west of the Mississippi. The settlers somewhat romantically gave their town a hybrid name composed of Dakota ‘Minne’ (water) and Greek ‘apolis’ (city). The original settlers were from English-speaking New England, New York, and Canada. Later immigrants moved there from Scandinavia, Germany, and Southern and Eastern Europe, speaking languages other than English and settling mostly in what is now Northeast Minneapolis. Italians lived in “Bohemian flats” close to the riverbank.

Higher Education in Minnesota

Also in 1854, a group of English-speaking Methodists founded Hamline University in Red Wing, located to the south and just 100 miles east of German-speaking New Ulm. Women students would be expected to learn French and German while male students learned Greek and Latin. The Methodist founders (shown above) seemed a more relaxed group than those who founded the University of Minnesota six years later (shown below).

In 1861, after Minnesota had become a state, the University of Minnesota was officially founded as an English-speaking university* with the help of John Sargent Pillsbury, an entrepreneurial New Englander. Over the next few decades, other English-speaking colleges and universities were founded; in order, they were: Carleton College (1866), Augsburg College (1872), Macalester College (1874). St Olaf College, founded in 1875, was the only bilingual institution of higher education, offering classes in either Norwegian or English. All the others were English medium, including “normal schools” that later became state teachers’ colleges: Winona (1858), Mankato (1868), and St Cloud (1869). The beginning of the 20th century saw the founding in St. Paul of the two Catholic colleges of St Thomas (1903) and St Catherine (1905). With the one exception of St Olaf, higher education in Minnesota was English-medium – befitting the state’s deep New England roots and values.

Driving the Dakota from Minnesota

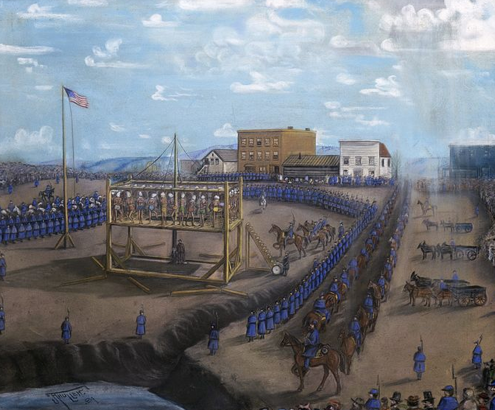

By 1862, after numerous federal government treaty violations and defaults on payments for food, large numbers of Dakota families were starving. In 1862, a small group of frustrated young Dakota-speaking militants attacked Ridgely and New Ulm, triggering a brief war that took the lives of between 450 and 800 white settlers and some 21 Dakota (Carley, 1976:1; Wingerd, 2010:306-307). Atrocities were committed on both sides before Sibley’s troops quelled the uprising. In the end, 303 Dakota men were convicted and condemned to death after speedy token trials conducted in English with the aid of interpreters. Minnesota Episcopal Bishop Whipple appealed to President Lincoln who commuted most of their sentences, but on the day after Christmas, Dec. 26, 1862, 38 Dakota men were hanged in Mankato, in what was then, and still remains, the largest mass execution in U.S. history (Lass, 1998: 130-133; Wingerd, 2010: 313-327).

Following the execution, 1600 Dakota women, children, and elders spent the cold winter of 1862 in a crowded internment camp on the river flats below Fort Snelling; more than 200 died. In the spring of 1863, Gov. Ramsey ordered all Dakota people to be “exterminated or driven forever” from Minnesota, and a federal law made it illegal for Dakota people to live in Minnesota. Most of the exiles went to South Dakota and Nebraska (Wingard 2010: 331-332). It was not until May 2013 that Governor Dayton repudiated Ramsey’s remarks, and flew Minnesota flags at half-staff in a day of reconciliation (Brown 2013).

After the Dakota War

After the Dakota War and over the next 20 years, immigrants from many nations in Europe, speaking many different languages, continued to pour into Minnesota land that was now emptied of its Dakota inhabitants. Most new immigrants were unskilled, illiterate workers from southern and eastern Europe & Russia (Kunz 1991), but many literate immigrants found ways to stay in touch with each other through native language newspapers. The Svenska Amerikanska Posten (Swedish American Post) for example began publication in 1885 and continued until 1940. It was founded not only to provide news from back home but also information on the ways of American culture and politics; it even supported the learning of English (Anderson, 2014) because English had become the common language of schooling and government, and immigrants now had to learn English to live in Minnesota.

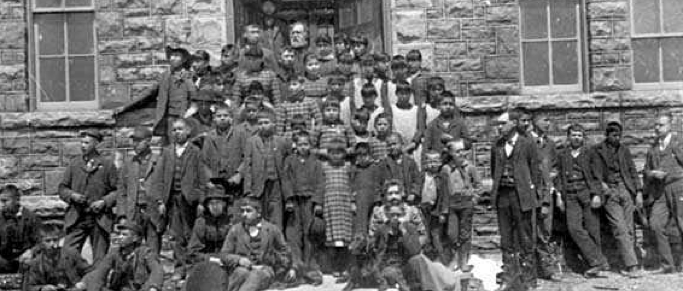

1887 saw the passage of the federal Dawes Act, which opened reservation lands to homesteaders and promoted the assimilation of American Indians across the nation. A key part of that assimilation was linguistic. Beginning in 1887, federal Indian boarding schools were established for indigenous language speakers in every state, including Minnesota. Children were given European names and forbidden to speak their languages. The teaching approach was simple and brutal: children were separated from their families and punished when they spoke anything but English. There were several Indian boarding schools in Minnesota, including the one pictured below in Pipestone.

Jim Northrup was an Ojibwe child at Pipestone Indian School before it was finally closed in 1953 (surprisingly recently). Northrup wrote this poem about his experiences:

“Ditched,” by Jim Northrup (1933)

A first grader, a federal boarding school. Pipestone.

Said Aaniin to the first grown up, got an icy blue eyed stare in return

Got a beating from a second grader, for crying about the stare.

Couldn’t tell maw or dad, both were 300 miles away

Couldn’t write, didn’t know how. Couldn’t mail, didn’t know how.

Runaway, got caught. Got an icy blue eyed stare and a beating.

Got another beating from a second grader for crying about the blue eyed beating

Institutionalized…..Toughed it out …. Survived

Needless to say, the outcome of this teaching approach – survival – is hardly a worthy goal in English learner education. One of the common narratives of the boarding school experience by those who went through it was that they were not allowed to use their native languages; this resulted in growing native language loss, creating linguistic divides between families and a newfound disconnect between boarding school survivors and their families.

During this time, English use spread through virtually all schools and communities in Minnesota. During the last decade of the 1800’s, most St. Paul churches that had been holding services in languages other than English (e.g. German, French, Swedish, Polish) switched to English. By the turn of the century, most schools were teaching English to immigrant families.

Into the Twentieth Century

In 1897, Neighborhood House was founded in St. Paul by Eastern European Jews to be a community support resource for social services to immigrants. The organization provided services such as English language, sewing and cooking classes (presumably taught in English), and employment referrals (Kunz 1991). The Jewish, French, German, Irish, and Swedish speaking immigrants in Neighborhood House would later be replaced by speakers of Czech, Slovak, Italian, Polish, Spanish and Hmong.

As the 20th century advanced, more and more “foreign students” were admitted to Minnesota’s English-medium universities. In 1914 the first three students from China were admitted to the University of Minnesota; they turned out to be stars on the soccer team, shown in the photo to the left. Many Chinese foreign students came to the University until 1949, the year the Peoples’ Republic of China was established and most international travel between the U.S. and China stopped. Foreign students from other countries took their places, with increasing numbers entering all Minnesota’s colleges and universities.

World War I brought a period of anti-German xenophobia among English speakers around the globe, including those in Minnesota. The St. Paul schools stopped teaching German, for instance, and the German Rathskellar (beer hall) in the basement of the Minnesota State Capitol, with its decorative walls featuring sayings in German, was closed. But after WWI, immigration to the U.S. resumed. For example, Spanish-speaking immigrants formed a Hispanic community in West St. Paul, which had its own community institutions such as Our Lady of Guadalupe Church. In subsequent years, Spanish speakers continued to flock to Minnesota, finding work and new homes throughout south and southwest Minnesota (Lass, 1998).

Post World War II

After World War II, the US invested in its infrastructure, and provided subsidies for higher education. The Fulbright Educational Exchange Program was established in 1945, when Senator J. William Fulbright introduced a bill in the United States Congress that called for the use of surplus war property to fund the “promotion of international good will through the exchange of students in the fields of education, culture, and science.” Colleges and universities began seriously recruiting foreign students as part of the effort to rebuild internationally. In 1950 Macalester College’s president started flying the UN flag right under the US flag, and many future world leaders attended that school. For example, in 1961, Kofi Annan, future Secretary General of the United Nations, graduated from Macalester. Such foreign students, already highly educated in their own countries, now needed to learn English at very high levels, and required highly professional instruction in what came to be known as English as a second language (ESL). The U.S. government and colleges invested many resources to develop high quality ESL instruction in higher education to support them.

By 1948, 25,000 foreign students were enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities, and over the next decades their numbers expanded. During the same period, increasing numbers of immigrants came to the U.S. In 1965 the Immigration and Nationality Act opened the door to immigrants from Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Southern and Eastern Europe who were also English language learners.

In 1948, to meet the needs of increasing numbers of foreign students in American higher education, the National Association of Foreign

Student Advisors (NAFSA) was founded. NAFSA included a group of “English language specialists.” In 1964 they met in Minneapolis, where the ESL group within NAFSA began discussing whether to separate and form their own organization. Later that year this group held a separate conference in Arizona that 700 people attended, far more than expected.

The next year, in 1965, Harold B. Allen, a University of Minnesota linguistics professor and expert on American regional dialects, announced the results of a national survey of ESL teachers who supported the idea of a separate professional association. In 1966 a constitution for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) was approved, and Harold B. Allen was elected the first president of TESOL.

In 1968, Betty Wallace Robinett became a professor in the University of Minnesota Linguistics Department and director of both the M.A. program in English as a Second Language and the Minnesota English Center (MEC), an intensive English program for international students. She instilled very high standards in the TESL professionals she educated; for example, the 2-year curriculum for the M.A. program required a full semester of linguistics, another of phonetics, a full year of English grammar, an English literature course, and 2 years of foreign language study, as well as three final qualifying papers (Plan B papers).

As TESOL President in 1973-74, and also the first editor of the TESOL Quarterly, Prof. Robinett was a professional role model for her graduate students. In 1974, a group of them traveled to Denver to attend the national TESOL conference. Inspired, they returned to Minnesota determined to establish a TESOL affiliate in Minnesota. In October, 1976, Kathleen Jacobson, Joyce Biagini, Deirdre Kramer, Wendy Weimer, JulieAnn Kvalbein and others called for the first Minnesota TESOL Affiliate organizing meeting, where MinneTESOL was created (Hansen 2014). During its first four years, 1976-1980, MinneTESOL met at Macalester College, with Kathleen Jacobson as its first president. In 1981, the MinneTESOL Journal was established, with Mark Landa as its editor at the University of Minnesota. Alumni of the University of Minnesota’s M.A. ESL program taught in colleges and universities across the state, establishing new programs to teach ESL to increasing numbers of recruited “foreign students” – by now, apparently the largest group of English learners in the state, all obviously highly educated and literate in their native languages.

The Peoples’ Republic of China reopened in 1974 and began encouraging academic visitors and tourism. In 1979 Prof. Robinett was part of a University of Minnesota delegation that traveled to China, where she was greeted (in English!) by many enthusiastic alumni with fond memories of Minnesota. On her return, Robinett became Associate Vice President of the University, and Elaine Tarone was hired to begin in Fall 1979 as Assistant Professor and director of ESL programs at the University of Minnesota.

Minnesota English Learners in the 1970s and beyond

The profile of the typical English learner in Minnesota began to change through the second half of the 1970’s. Beginning in 1975, after the end of Vietnam War, speakers of Vietnamese, Lao, and Hmong began moving to the Twin Cities.

The largest group, Hmong speakers, settled primarily in St. Paul, where they are still the largest Hmong-American community in the U.S. Many of these immigrants were not literate in any language – a new issue for ESL teachers in the area, and one that TESL professionals were ill-equipped to handle. It was fortunate that the Minnesota Literacy Council, founded in 1971 to teach illiterate native speakers of English, was able to expand in response, and began to train and organize volunteers to teach English to Hmong-speaking immigrants with limited formal schooling and literacy.

In 1982, Minnesota’s state department of education began requiring K-12 ESL licensure for public school teachers to meet the needs of growing numbers of immigrant English learners, and in that same year, the University of Minnesota opened its ESL licensure program. In 1984 Hamline University’s ESL licensure program began, and in 1985, the University of Minnesota started a dual licensure program (for ESL and foreign language public school teachers). Immigration continued to diversify Minnesota’s public schools, and beginning in 1990, Somali immigrants displaced by civil war were added to the mix, most settling in the Cedar-Riverside area of Minneapolis, directly adjacent to the University. Many of these Somali immigrants were illiterate, just as the earlier wave of Hmong immigrants had been (Bigelow 2010). By 2002, Minnesota had the largest Somali community in the U.S. and today is home to an estimated 25,000 Somali-Americans, or a third of all those in the U.S.

English Language Teacher Education into the 21st Century

Many TESOL and foreign language teacher education programs were founded in the 1990’s. In 1991 Hamline University started its TEFL Certificate Program; in 1993, CARLA was founded as a US Department of Education Title VI Language Resource Center to promote foreign language learning and teaching. CARLA focused especially on in-service professional development for teachers of all languages, whether world language or English as a second language, and hosted annual summer institutes and a biennial International Language Teacher Education Conference that brought nationally prominent teacher educators to the area. Other colleges and universities also founded TESOL teacher education programs in the ‘90’s, including St. Cloud State and Mankato State University.

Beginning about 2004, Twin Cities’ college and university deans and vice presidents instituted massive reorganizations of TESOL and ESL programs in an effort to cut costs as legislative allocations for higher education waned. For example, in 2004 Hamline University’s TESL program structure was reorganized, and the University of Minnesota’s College of Liberal Arts Dean Steven Rosenstone closed the Minnesota English Center, citing financial constraints. Two years later, because the University of

Minnesota couldn’t successfully recruit international students without an intensive English program, a new one, the Minnesota English Language Program (MELP), (re)opened within the University’s College of Continuing Education. In 2005, the University of Minnesota closed General College, which included the Commanding English Program for immigrant English learners on campus. In 2009 the MinneTESOL resource center at Hamline closed. In 2011 the University of Minnesota College of Liberal Arts Dean’s office again took action, closing the M.A. ESL program. Like the intensive English program earlier, the graduate program re-opened in a different college, this time the College of Education and Human Development, where it is now called the M.A. in TESOL.

There was a very good reason most of these programs did not stay closed: They were still needed, not just to prepare ESL professionals to teach international students at the state’s colleges and universities, but also to meet the increasingly diverse English learning needs of Minnesota residents on and off campus.

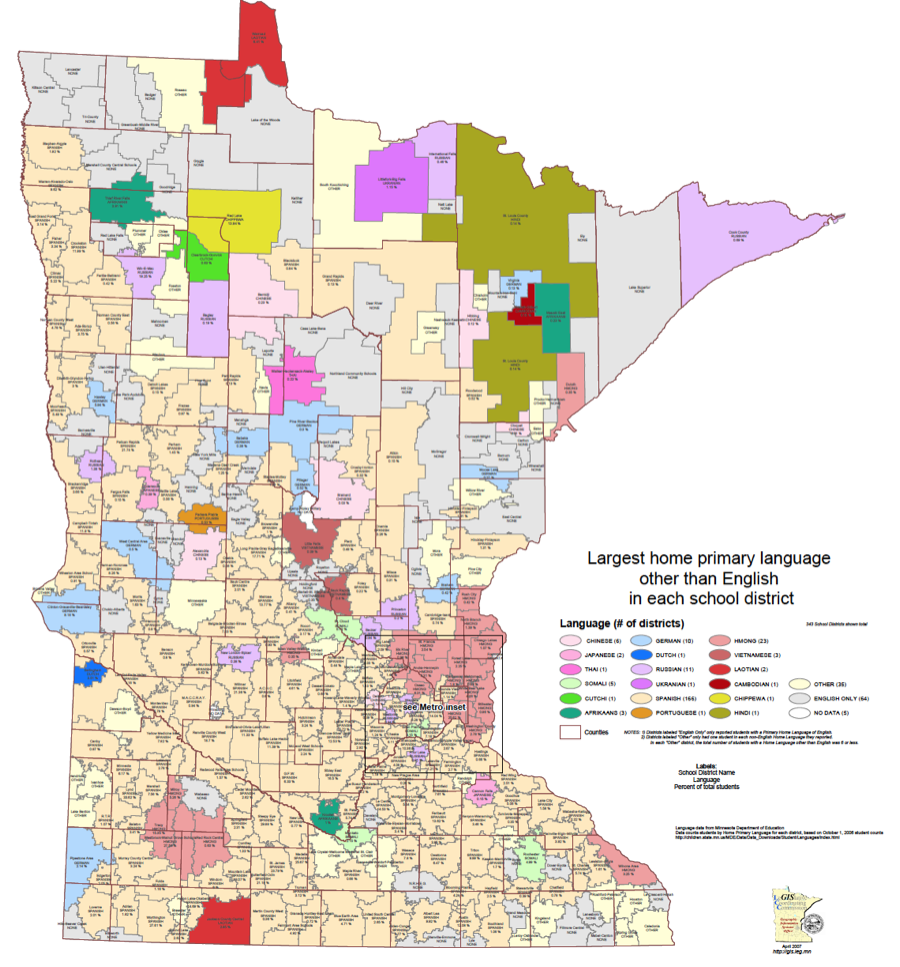

In 2007 census figures showed almost 10% of Minnesotans had a home language other than English; the top 6 of these were (in order) Spanish, Hmong, Somali, Vietnamese, Russian and Lao. Just 7 years later, in 2014, the fourth largest home language was Karen (spoken by low literate immigrants from Myanmar).

But the linguistic diversity of Minnesota’s citizens today is not restricted to immigrants’ home languages. Late in the 20th century, K-12 language immersion programs for Minnesota’s English-speaking students began popping up like mushrooms all over the state. Today there are over 90 immersion programs offering elementary students whose home language is English, opportunities to become bilingual in Spanish, French, German, Chinese, or Korean. And, almost miraculously, the Ojibwe and Dakota languages were again being taught and learned in immersion schools in Minnesota.

The truth is that Minnesota never has been a monolingual English place. It has been, and is, a multilingual place in which English plays the central role, but where other languages have essential roles to play as well. There is at present a very rich multilingual and English learner history and environment in Minnesota: strong teacher education programs for both ESL and foreign languages, for K-12 and adult learners, and for domestic, international and immigrant students. As people move more and more freely around the globe, as markets internationalize, as our children move not just out of state, but out of the country, our horizons have expanded exponentially. There is increasing need for Minnesotans to know English and other languages. Not only has Mogadishu moved to the Mississippi (Bigelow 2010), but Minnesota’s young people are moving away to live in places around the globe.

Lessons from History

What can we learn from this brief illustrated history? What principles can we, as language teachers and language teacher educators, take away that might be useful as we educate English learners?

- The goal of English language education remains the same: Minnesota needs language learners to achieve high levels of English but also to maintain and develop their home languages to have a high level of bilingual competence — especially essential now in the 21st century’s globalized political scene and economy. Second language acquisition (SLA) researchers and applied linguists such as the Douglas Fir Group (2016) agree that multilingualism is good, not just for the brain but also for the economy, for global learning, and for national security. As we have seen, past attempts in Minnesota to turn English learners into English monolinguals have not gone so well (see Northrup 1993). A better goal is to help them become highly functioning bilingual speakers, in English and their home language. By respecting the English learner’s home language, we respect who that learner is. By maintaining high standards for both languages, we open new opportunities for all learners.

- Bilingualism is not just for immigrants. More and more parents who speak English in their homes are sending their children to the growing number of language immersion schools across Minnesota, to give them the advantage of becoming bilingual speakers of English and Spanish, French, Chinese, German, or Ojibwe. This means English learners are not the only ones in Minnesota trying to become bilingual to deal with 21st century realities.

- Both foreign language and ESL programs need to provide academic and professional skills in both the first and second language. We are not just teaching “survival” language for poor immigrants or social language for rich tourists. As language teachers, we seek to encourage high levels of development of English and other languages to meet academic and professional goals.

In the 21st century, mastery of “English only” will not be enough. The goal of ESL programs as well as of foreign language and immersion programs must be to make sure all graduates are as bilingual and bicultural as possible in English and another world language. Future ESL programs should nurture students’ home languages while teaching them English, and future immersion and foreign language programs should nurture students’ home language, English, while teaching them a foreign language. The outcome will be an even brighter future for multilingual Minnesota.

References

Anderson, Jim (2014, Dec 15) Swedish-language papers digitize. Minneapolis Star Tribune, p. A9

Association of Public and Land Grant Universities (n.d.). The land-grant tradition. Accessed June 15, 2016. http://www.aplu.org/library/the-land-grant-tradition/file

Bigelow, Martha (2010). Mogadishu on the Mississippi: Language, racialized identity and education in a new land. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bond, J. Wesley (1853). Minnesota and its Resources. New York: Redfield.

Brown, Curt (2013). Dayton repudiates Ramsey’s call to exterminate Dakota. Star Tribune, May 2, 2013.

Carley, Kenneth (1976). The Sioux uprising of 1862. Saint Paul: The Minnesota Historical Society.

Clemmons, Linda (2000). ‘We find it a difficult work’: Educating Dakota children in missionary homes,

1835-1862. American Indian Quarterly 24, 4: 570-574.

Dahlheimer, Thomas Ivan (n.d.). History of the Dakota people in the Mille Lacs area. Accessed Nov. 1, 2015. http://www.towahkon.org/Dakotahistory.html

Douglas Fir Group (2016). A transdisciplinary framework for SLA in a multilingual world. Modern Language Journal 100 (Supplement 2016): 19-47.

Gunn, George Henry (1939). Garrioch at St Peter’s. Minnesota History, 20:119-128. Accessed June 28, 2016. http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/20/v20i02p119-128.pdf

Hansen, Adele (2014). Historical record. MinneTESOL Blog. Accessed Nov. 1, 2015. http://minnetesol.org/blog/index.php/news/minnetesol-leadership-and-conference-historical-record/

Huber, Molly (2014). MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. “Pipestone Indian Training School Baseball Team.” Accessed Nov. 1, 2015. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/pipestone-indian-training-school-baseball-team

Keillor, Steven J. (2008). Shaping Minnesota’s identity: 150 years of state history. Lakeville, MN: Pogo Press.

Kollenborn, K.P. (2012). “If they’re hungry, let them eat grass or their own dung.” Blogspot, 19th century American history, Minnesota. Accessed Nov. 1, 2015. http://kpkollenborn.blogspot.com/2012/11/if-theyre-hungry-let-them-eat-grass-or.html

Kunz, Virginia Brainard (1991). Saint Paul: The first one hundred and fifty years. St. Paul: The St Paul Foundation.

Lass, William E. (1998). Minnesota: A history, 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Morton, Zylpha (1947) Harriet Bishop: Frontier Teacher. Minnesota History Magazine, pp. 132-141. Accessed Nov. 1, 2015. http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/28/v28i02p132-141.pdf

NAFSA (n.d.) The history of NAFSA: Association of international educators. Accessed June 15, 2016. http://www.nafsa.org/Learn_About_NAFSA/History/

Nord, James (2011) The Untouchable U: Older than the state, the University governs itself. Twin Cities Daily Planet (Sept. 21, 2011). Accessed Nov. 1, 2015. http://www.tcdailyplanet.net/news/2011/09/21/untouchable-u-older-state-university-minnesota-governs-itself

Northrup, Jim (1993). Walking the Rez Road. Voyageur Press.

Wingard, Mary L. (2010). North country: The making of Minnesota. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

Woodard, Colin (2011). American Nations: A history of the eleven rival regional cultures of North America. New York: Viking.

*With the Morrill Act in 1862, it became a land-grant university which had federal support to offer agricultural and mechanical arts education to its citizens.

Thanks to Martha Bigelow, Karin Larson and Grant Abbott for contributions to the paper. Thanks to Rachel Juen, Employee, Historical Fort Snelling, for suggesting references and resources.