Hamline Professor Emeritus Ann Mabbott shares how experienced ESL teachers can take the skill set they have developed here to teach abroad.

Key words: English Language Specialist, teach abroad, academic language, content-based instruction

Would you like to teach overseas? For the first time or once again? ESL professionals are all enthusiastic about languages and cultures, and in helping language learners to acquire English. In addition, most of us have an interest in traveling internationally, and our experience teaching English to immigrants and refugees in the United States can be foundational for international work. In this article, I will discuss employment opportunities, ones that are relatively well paid, with the U.S. State Department for experienced ESL teachers. I will describe how I used the work I have been doing in the United States with teaching academic language to support content instruction in an international context, with bilingual teachers in Spain. Finally, I will provide some links and resources to additional overseas English teaching positions for teachers of varying levels of experience.

US State Department English Language Programs

The English Language Program Office in the U.S. State Department offers two types of international teaching opportunities for ESL professionals. The first, the English Language Fellows program, is for experienced English teachers with an M.A. or equivalent experience who are able to teach abroad at universities and other academic institutions for 10 months. It allows you to take dependents with you, and provides a stipend for dependents. The prospect of teaching in a country such as Nepal or Malaysia for 10 months has always appealed to me, and if it does to you, look into this opportunity.

The second program is called English Language Specialists. The Specialist program sends English teaching experts to countries who request them to provide professional development lasting from two weeks to three months. Candidates apply to be an English Language Specialist, and then are accepted into a pool of “experts.” Once a country makes a request for a particular type of project, representatives of the country are sent several resumes to consider. The host country chooses individuals to interview over Skype, and then invites their top candidate to come. The types of projects that Specialists deliver vary widely, from using drama in English instruction to proving workshops on communication skills for UN Peace Keeping Troops.

Sharing Academic Language Instruction Approaches in Spain

In my case, I finally had time to pursue my desire to do more teaching overseas when I retired from my faculty position at Hamline University. I presented the English Language Specialists program a resume which included my long-time work teaching content teachers (math, science, social studies) how to teach content and the supporting academic language needed at the same time, along with credentials in language proficiency assessment and online course development. So far, I have gotten invitations to teach in Spain and Russia.

Spain, the country I worked in first, had been starting many bilingual immersion programs as a way to provide young people more international opportunities and to support the internationalization of its economy. Together with the cultural attaché office in the U.S. embassy in Madrid, representatives of the bilingual programs in Spain put together a program of conference presentations and teaching at four different universities in Spain, which they wanted the Specialist to provide.

One of the things that I had to convince myself of and state publicly at the beginning of every talk I gave in Spain is why what I could bring from my Minnesota immigrant and refugee education perspective was equally relevant in bilingual immersion schools in Spain. Most of the k-12 students with whom the Spanish teachers work are not immigrants or refugees, but what we have in common is the need to teach content in a language in which the students are not yet fluent. We arrived at two goals:

- Preparing content teachers to meet the linguistic and cultural needs of the English learners in their classes;

- Preparing English teachers to coach their content colleagues in multilingual classrooms.

Fortunately, I was able to draw on the work of the Hamline University’s English Learner in the Mainstream (ELM) project, which was funded by the U.S. Department of Education in 2016. In both Spain and in Minnesota, we are changing the roles of both teacher educators (putting a new emphasis on complementary language and content instruction) and ESL teachers (insisting that one of their roles be coaching their mainstream colleagues).

The theoretical foundations of the ELM work that I drew on for my work in Spain are:

- Accessible Instruction (Gibbons, 2015; Wong-Fillmore & Snow, 2000)

- Systemic Functional Linguistics (Brisk, 2015; Halliday, 1978; Schlepegrell, 2004)

- Academic Language (Cummins, 2008; Dutro & Moran, 2003; Zwiers, 2008)

- Interaction (Swain, 1995; Zwiers & Crawford, 2011)

- Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (Heath, 1983; Delpit, 1998; Gay, 2000; Ladson-Billings, 1995; Paris, 2012)

- Instructional Coaching (Aguilar, 2013; Knight, 2007) (for teacher coaches)

Instructional coaching, although it is listed last among the foundations, is crucial, and even newer to teachers in Spain than the U.S. We all tend to come from a background of independent teachers who reign in their own classrooms, and so teachers have to learn to trust each other as supportive professionals working together for the benefit of students.

Accessible instruction includes multi-modal teaching practices that make it possible to understand content even when one’s language proficiency is limited. Systemic functional linguistics urges teachers to think about the function of the academic texts they are using, and to teach at the:

- Word level (semantics, collocations, morphology and phonology);

- Sentence level (syntax and grammar); and

- Discourse (genre) level.

Most content teachers, since they are not trained to be language experts, tend to think of language needs in terms of new vocabulary, or words that are bolded in textbooks, and need to be encouraged to expand their teaching beyond semantics. They also need to learn about syntax and discourse patterns for their disciplines.

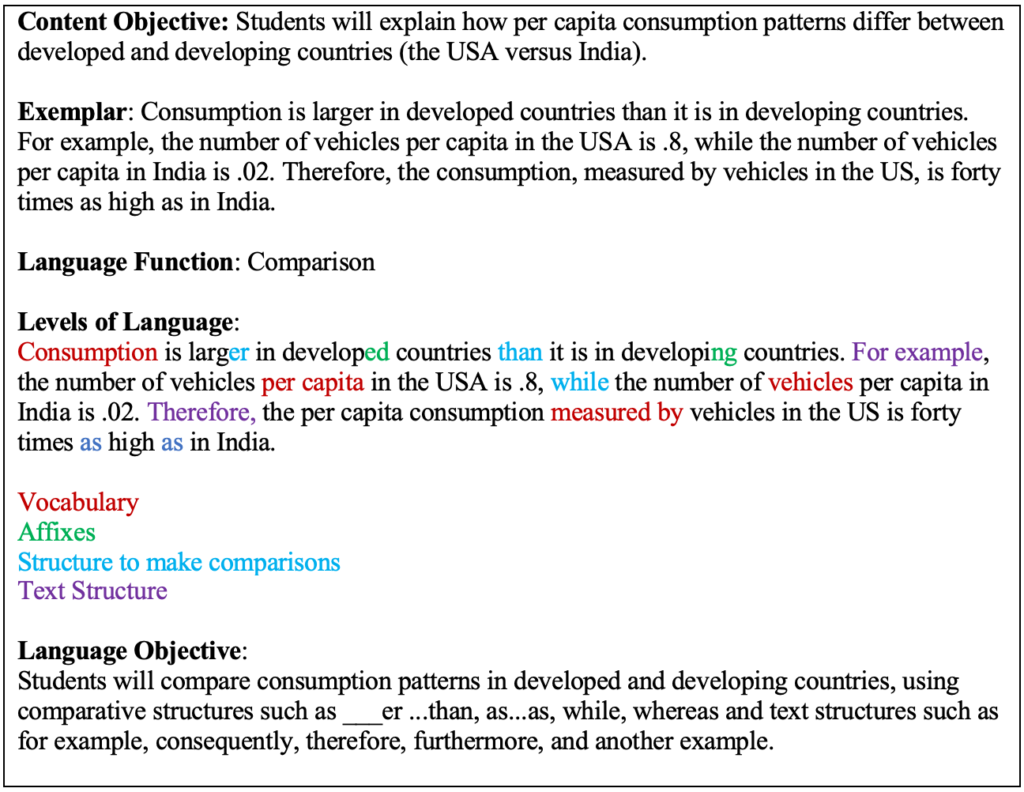

Fortunately, ELM provides wonderful resources for teaching about academic language and how to write language objectives that support content instruction that everyone can access. One approach to writing them are the following steps:

- Identify the content objective.

- Write an exemplar of what you want students to learn.

- Determine what the language function is that will support the content.

- Identify language at the word, sentence and discourse level that needs to be taught to fulfill that function that will support the language objective.

Both content teachers in Spain and content teachers here do not have pedagogical linguistics training, and it is up to us as ESL professionals to support them. ELM also provides a worksheet with more support for writing academic language objectives.

One example I like to use when helping teachers learn how to write language objectives comes from a ninth-grade social studies class I observed in Minneapolis. The steps above are followed with the social studies example below in Figure 1.

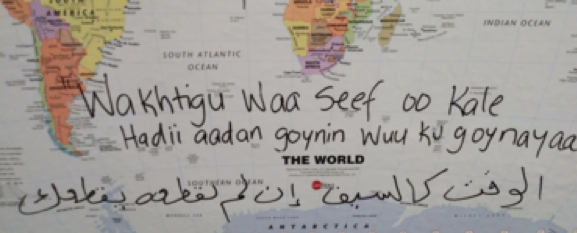

When working in Spain, I changed the context from the U.S. to a comparison between per capita consumption in Spain compared to that of India, making the instruction culturally relevant for the context in which I was teaching. I also used bull fighting, a Spanish cultural tradition which is very controversial in Spain right now, as the setting for a discussion about the different types of academic or professional language. After showing a picture of a bullfighter, I had teachers write about the picture from the perspectives of the bullfighter, the bull breeder, a veterinarian, an animal rights activist, a journalist, and the tourism minister. We analyzed the language that each different professional might use, and determined what function each was fulfilling, as well as what kinds of language would need to be taught to fulfill those various functions.

Interaction is the last foundation that my work here and in Spain both addressed. As ESL professionals, we all know that academic language is not acquired efficiently when students do not get a chance to use it in writing and speaking (Swain, 1995; Zwiers & Crawford, 2011). An outstanding example of interaction in a content class on environmental issues that includes a large number of English learners can be found in Sarah Horowitz’s Teaching Channel video, Teaching Evidence-Based Academic Discussions. I ask teachers to watch the video and then identify:

- What language needs to be taught for students to accomplish her objective of having students hold an evidence-based discussion about environmental issues?

- How would you classify that language?

- How would you teach that language?

- What scaffolds does Sarah use to include the more reluctant or lower language proficiency students?

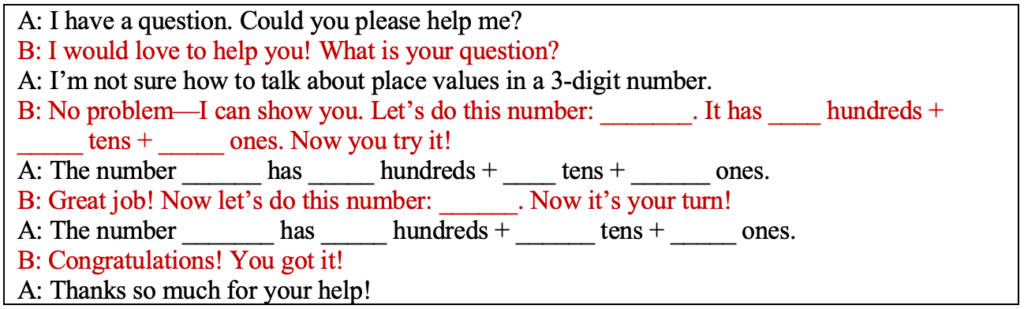

When students have a lower level of proficiency, Watson’s (2015) RISA oral interaction approach can be quite effective. RISA stands for routine, integrated, structured, and academic. They are similar to the dialogues we had to memorize in world language classes, but the topics of conversation are academic, rather than social. They are done routinely, integrated into content objectives, with the structure provided, and academic in nature. An example that Watson provides is in Figure 2.

The dialogue can be about any topic in the curriculum, and by reciting it, and then reversing roles, students can learn the necessary academic vocabulary and language structures, as well as the pragmatics involved in oral interaction. As students become more proficient, the support structure provided can gradually diminish. Since many of the students in Spanish classrooms have lower levels of English proficiency, Spanish teachers loved the RISA dialogues.

The last thing I shared with the teachers in Spain is the ELM classroom observation form. As in the United States, classroom observations in Spain tend to not address some of the crucial issues for second language classrooms. The ELM observation form has sections on language proficiency of the English learners, access to instruction, language objectives that support the content, and interaction. It can also be revised to meet needs particular to a school or classroom. I encourage anyone who has an opportunity to work with content teachers to use the form for recording classroom observations and discussing how instruction might be modified to meet the needs of English learners.

What I have learned by teaching abroad is that the work we are doing here with immigrants and refugees is very transferable to instruction in a second language in other countries. In fact, I just got back from my second experience as an English Language Specialist. This time the trip was to Russia, where the context was largely for university-level classes that are taught in English. My major assignment was teaching academic language and content at the same time, but several additional requests came up. Some teachers wanted to know how to differentiate instruction in a content class for students with different levels of English proficiency. Differentiation is another area with which American ESL teachers have a lot of experience, as they are often teaching classes with varied proficiency levels. Russian teachers were also interested in understanding higher-order thinking skills and applying them to critical reading, writing, and speaking. Finally, if you have written an M.A. or doctoral thesis, those skills are very much in demand as well. Many university-level Russian teachers are being asked to publish for the first time, and are not familiar with reading or writing either pedagogical or research papers. If you are interested in sharing your skill set, consider applying to be an English Language Fellow or Specialist with the U.S. State Department. My assignments were in Spain and Russia, but there are similar requests from all over the world. Below I also list other international opportunities for experienced ESL professionals to consider.

Other International Teaching Opportunities

- English Teaching Assistants The Fulbright English Teaching Assistant programs place grantees in schools overseas to supplement local English language instruction and to provide a native speaker presence in the classrooms. View the countries offering English Teaching Assistant Awards here.

- The Fulbright Study/Research Award is the traditional award opportunity where a candidate designs a proposal for a specific country. Read the Country Summaries for more information.

- The Fulbright Teachers for Global Classrooms Program (TGC) is a professional development fellowship for elementary, middle, and high school teachers from the United States to participate in a program aimed at globalizing U.S. classrooms. The fellowship includes an online professional development course, a Global Education Symposium held in Washington, D.C., and a two to three-week international field experience.

- Transitions Abroad: Guide to work, study, and live abroad

- TEFL Guide to Finding Jobs Overseas

References

Aguilar, E. (2013). The art of coaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Brisk, M. E. (2015). Engaging students in academic literacies: Genre-based pedagogy for k-5 classrooms. New York: Routledge.

Cummins, J. (2008). BICS and CALP: Empirical and theoretical status of the distinction. In B. Street, & N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Language and Education (2nd ed.) (pp. 71-83). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media LLC.

Delpit, L. (1988). The silenced dialogue: Power and pedagogy in educating other people’s children. Harvard Educational Review, 58(3), 280-299

Dutro, S., & Moran, C. (2003). Rethinking English language instruction: An architectural approach. In G. G. Garcia (Ed.), English learners: Reaching the highest level of English literacy (pp. 227-258). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gibbons, P. (2015). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: teaching English language learners in the mainstream classroom. Portsmouth, N.H: Heinemann.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Knight, J. (2007). Instructional coaching: A partnership to improving instruction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Ladson-Billings, G. J. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Education Research Journal, 35, 465-491.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy: A Needed Change in Stance, Terminology, and Practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93-97.

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2004) The language of schooling: A functional linguistics perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Swain, M. (1995). Three functions of output in second language learning. In G. Cook, & B. Seidlhofer (Eds.), Principle and practice in applied linguistics: Studies in honour of H. G. Widdowson (pp. 125-144). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Watson, J. (2015) Watson Educational Consulting: Effective instruction and assessment for diverse learners. Accessed 11 November, 2019 at https://www.watsoneducationalconsulting.com

Wong-Fillmore, L., & Snow, C. E. (2000). What teachers need to know about language. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. Retrieved from http://www.elachieve.org/images/stories/eladocs/articles/Wong_Fillmore.pdf.

Zwiers, J. (2008). Building academic language: Essential practices for content classrooms. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Zwiers, J., & Crawford, M. (2011). Academic conversations: Classroom talk that fosters critical thinking and content understandings. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.