Translanguaging pedagogy has largely focused on K-12 learners in content classrooms. However, collaborative translation is one translanguaging literacy practice that is well-suited for adult English as a Second Language (ESL) learners with thoughtful adaptations based on text choice, course objectives, and learner characteristics.

Keywords: Adult Education, Higher Education, SLIFE, Translanguaging, Language Teaching, Multilingualism

Translanguaging has emerged as an increasingly popular framework in English language learner education (García & Li Wei, 2014; Lin & He, 2017). At its strongest variation, translanguaging as an ideology describes a unitary languaging system and calls for learning environments that enable multilingual learners to use their entire linguistic repertoire (García & Li Wei, 2014). To achieve this, several pedagogical interventions such as collaborative dialogue, multilingual writing and word walls, translation, and multilingual listening/visual resources have been suggested for incorporating translanguaging into the classroom (García & Li Wei, 2014). Thus far, translanguaging has been studied most extensively in K-12 content classrooms. However, the benefits of translanguaging are not limited to this setting, and research suggests that adult learners can also benefit substantially from a translanguaging approach (Turnbull, 2019).

Translation is one of the suggested pedagogies for incorporating translanguaging in the classroom. In an effort to shed light on how this translanguaging strategy can be adapted for adult education contexts, this paper will focus specifically on pedagogical translation and the work of Project TRANSLATE (Teaching Reading And New Strategic Language Approaches to Emergent bilinguals, see Figure 1). All data from Project TRANSLATE described in the adaptations below is based on observations and findings from ongoing research conducted in a middle grade classroom in the Midwest. This work has been completed by a team of researchers that includes the author, who has also been an English as a Second Language (ESL) educator for adult language learners for five years.

Project TRANSLATE uses collaborative translation between the target language and students’ home languages as a literacy intervention. To date, this translanguaging pedagogy has been used only in K-12 content-based settings. However, with some adaptation, the TRANSLATE protocol is rich for use in adult English language learning classrooms.

Translanguaging – One Word, Two Meanings

As an ideology, translanguaging views language as a unitary meaning-making system (García & Li Wei, 2014). Translanguaging intentionally enables multilingual speakers to leverage their entire linguistic and multi-modal repertoires in communication with and about people, objects, places, and spaces (García & Kleifgen, 2019). The goals of translanguaging are to deepen students’ understanding of texts, generate more diverse texts, develop students’ confidence, and foster metalinguistic awareness. García et al. (2021) situate translanguaging as part of asset-based pedagogy and firmly reject the abyssal thinking that places mainstream white English at the top of the language hierarchy. Translanguaging in the classroom is therefore a matter of both educational efficacy and social justice equity (Shohamy, 2011).

As a pedagogy, translanguaging suggests that teachers should leverage students’ full linguistic repertoires when teaching a new language (David et al., 2019) and that multilingual practices should be regularly implemented in the classroom (García et al., 2021). Lin & He (2017) put it even more clearly: “Translanguaging can function as both pedagogical scaffolding strategies and opportunities to negotiate and affirm students’ identities and build teacher-student rapport” (p. 237). However, while many teachers may share a belief in the benefits of students using their full linguistic repertoires, the reality of how that is expressed in the classroom varies greatly.

Oaxaca, Mexico

Some teachers used translanguaging as a scaffold (for example, providing instructions in students’ first language [L1]) whereas others explicitly rewarded the use of translanguaging (for example, in narrative projects) when asked to integrate translanguaging into assessments.

Studied by Schissel et al., 2021

Basque Country, Spain

University-level content teachers fell into one of three categories based on their use of the target language in the classroom:

- virtual position (target language only)

- maximal position (as much target language as possible with some flexibility)

- optimal position (judicious use of students’ L1 to enhance learning).

Teachers’ use of translanguaging was typically reflected in their materials, though not necessarily in their assessments.

Studied by Doiz and Lasagbaster, 2017

Project TRANSLATE

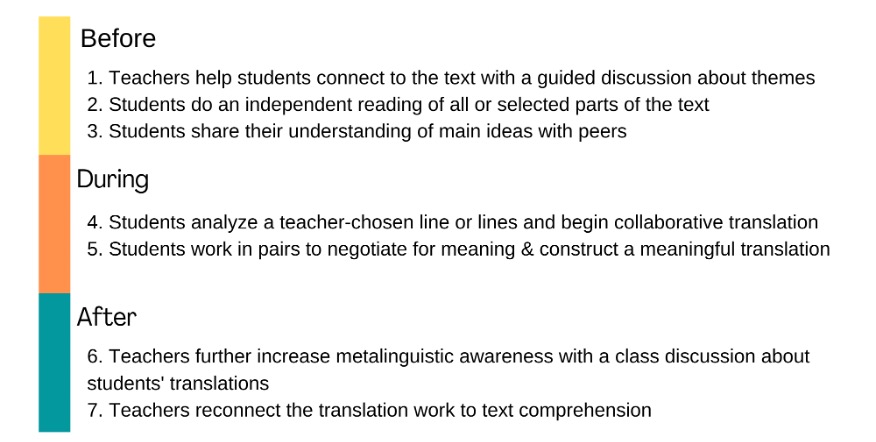

Project TRANSLATE is a collaborative translation strategy for literacy development that uses pedagogical translation as a social practice in which multilingual students’ daily translanguaging practices are mirrored in a classroom setting (David et al. 2019). The TRANSLATE protocol is situated within a guided reading framework (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996), and pedagogical translations are designed to leverage multilingual students’ skills to improve strategic reading, translation, and engagement. This, in turn, develops their English language proficiency as well. The TRANSLATE protocol as detailed by David et al. (2019) is grounded in social practice theory and consists of seven primary steps (see Figure 2).

Adapting Pedagogical Translation Across Contexts

What’s different between K-12 and adult ESL when it comes to pedagogical translation?

To date, the TRANSLATE protocol has been exclusively studied in K-12 classrooms. To bring this translanguaging practice to adult ESL education requires several adaptations. Adult ESL education and K-12 content classrooms use fundamentally different input texts in addition to having different course objectives and learner characteristics.

Different Standards, Different Texts

K-12 objectives for English language learners are typically bound to WIDA standards or other federally or state-mandated standards (Gottlieb, 2016). While teachers may have considerable freedom in their lesson planning, there is some consistency in standards across schools, districts, and states. There may be more variation for adult English learners. English curriculum taught as part of an Adult Basic Education program may be connected to a variety of federal standards such as the National Reporting Service Educational Functioning Levels, English Language Proficiency Standards, College and Career Readiness Standards, or may follow state-specific standards (Gonzalves, 2021). On the other hand, adults learning in an intensive English program that is affiliated with a specific school or institution may adhere to standards established by that program. Finally, English language programs established through non-profit organizations or other community education settings may have little to no formal standards process (Entigar, 2017). Adults in each of these learning environments are likely to have different goals and reasons for learning English – job acquisition, preparing for higher education, or survival English for newcomers to name a few. Using TRANSLATE with adult learners starts with a text that is relevant and engaging for their unique needs.

Adaptations: A good text for collaborative translation is relevant to students, tied to learning objectives, and not directly translatable. In an adult education context, relevancy is driven by the goals of the students. For example, if learners are highly job-focused, consider using authentic materials from a work report or dialogue between colleagues. However, fact-based writing tends to be more directly translatable and leaves fewer opportunities for meaning negotiation, so materials with work-related vocabulary as well as some figurative language and complex structures are ideal. On the other hand, if you are working with adults who are learning English in anticipation of shortly entering an English-speaking college or university, a rich text could address a theme central to existing course materials (including anything from civics to signing a lease!), cultural adaptation, or students’ future studies.

Content Class vs. ESL

Many K-12 English language learners are acquiring English in tandem with grade-specific content matter. Translanguaging in the classroom fosters critical opportunities for multilingual students to express their full content knowledge, regardless of English proficiency. In contrast, adult learners are more likely to be in an ESL class where acquisition of the target language is the primary objective, though this language learning is still often embedded in thematic, content-driven units. In these classes, the structure of adult ESL classes in many ways more closely resembles a K-12 foreign language classroom. This raises the question of how much translanguaging should be used in the classroom.

In a classroom where English learning is the primary objective, strong translanguaging is no less of an effective resource when applied strategically (Turnbull, 2019). In a study of Japanese young adults learning English as a Foreign Language (EFL) at a national university, Turnbull found that strong translanguaging, with strategic boundaries, enabled the intentional acquisition of specific linguistic features. Students in the strong translanguaging group produced richer student discussions and consistently higher scores for academic and creative writing than those in the weak translanguaging group where students were required to conduct research only in the target language. Strong translanguaging environments also produced richer student discussions, even when the final writing was produced in English (Turnbull, 2019). This study suggests that translanguaging pedagogies such as collaborative translation have significant potential in ESL and EFL classrooms.

Adaptations: As in K-12 classrooms, enabling the use of students’ full linguistic repertoires is key in adult English classes, but ESL classes strongly prioritize language learning in addition to thematic content. To emphasize linguistic connections in the TRANSLATE protocol, teachers can prompt discussion about specific language features, such as negation syntax or object placement, when comparing students’ home languages and the target language in addition to negotiating meaning. If teaching in an online learning environment, collaborative translation could take place using editable documents where students can write and compare translations. Then, meaning negotiation could occur either synchronously through a video call or asynchronously by leaving comments.

Similarly, instructors can ask students to highlight targeted language features in their home language (e.g., modal verbs) and English to identify and analyze notably similar or different structures between languages. In both in-person and online environments, classes with adults whose English course is also their primary source of target language input should place increased emphasis on reconnecting students with the text while using the target language.

Shifting from K-12 to Adult Education

The demographics of adult English learners may vary dramatically in a single program or even within a classroom. Some adult learners may come in with primarily oral proficiency, emergent literacy in their home language, or interrupted education (Pettitt et al., 2021). As a result, while K-12 schools frequently emphasize literacy-based instruction and learning, that is not necessarily effective for all adult English learners (Pettitt et al., 2021). Instead, adult learners with emergent literacy may perform better when instruction is based heavily on oral proficiency and gradually incorporates print literacy (Tammelin-Laine & Martin, 2014). Teaching that builds on learner strengths and the funds of knowledge that all students bring to the classroom also helps develop a learner-centered education environment (Parrish, 2019).

Adaptations: If working with adult learners with emergent literacy, additional modifications to the TRANSLATE protocol will be necessary. For example, the selected text and target sentences for translation must be available in an oral format. Written translations are valuable for meaning negotiation because they afford opportunities to visually compare translation syntax and consider orthographic patterns as part of meaning negotiation. However, an adapted process could rely on teacher collaboration or technology to create the translation record. For example, in our ongoing study, one teacher used a student dictation approach with Nepali-speaking students who were uncomfortable writing in their home language. To complete the translation and translanguage in oral and written modes, students read a text in English, created a translation based on Google Translate and their knowledge of Nepali, and their teacher wrote their verbal, Nepali, translations on paper phonetically using the English script.

Video technology similarly creates a translation record that allows students to review and compare their recorded translations as many times as necessary while implicitly increasing students’ technology literacy in the process (Vega-Carrero et al., 2017). Going forward, speech-to-text technology may also provide a scaffold for language learners with emerging print literacy. Additional scaffolding could be used for students with emerging literacy in their home language by reading the text aloud and conducting the entire activity orally. These adaptations can be used as intermediary steps to written translation if print literacy is a core objective.

The Takeaway

Facilitating translanguaging pedagogy is a key step to supporting equitable cultural and linguistic development for multilingual learners (García & Kleifgen, 2019; García & Li Wei, 2014; Shohamy, 2011). One strategy to try is pedagogical translation, which helps learners develop strong literacy practices and can be well suited for adult learners as well as K-12 contexts. You know your students best, so consider carefully what will be a meaningful text that meets their interests and your curricular objectives. Then, look for opportunities to negotiate meaning and highlight key language differences to spark metalinguistic conversations as students build multilingual connections in this dynamic classroom pedagogy.

Additional Reading:

- Designing Translingual Pedagogies: Exploring Pedagogical Translation through a Classroom Teaching Experiment by David, S., Pacheco, M., & Jiménez, M. (2019): https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2019.1580283

- Ofelia García shares her “whys” and “hows” of Translanguaging: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5l1CcrRrck0&ab_channel=MuDiLe2017

- CUNY Translanguaging Guide for Educators: https://www.cuny-nysieb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Translanguaging-Guide-March-2013.pdf

References

David, S., Pacheco, M., & Jiménez, M. (2019). Designing translingual pedagogies: Exploring pedagogical translation through a classroom teaching experiment. Cognition and Instruction, 37(2), 252-275. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2019.1580283

Doiz, A., & Lasagbaster, D. (2016). Teachers’ beliefs about translanguaging practices. In C. M. Mazak & K. S. Carroll (Eds.), Translanguaging in higher education: Beyond monolingual ideologies (pp. 157-176). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783096657-011

Entigar, K. E. (2017). The limits of pedagogy: Diaculturalist pedagogy as paradigm shift in the education of adult immigrants. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 25(3), 347-356. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2016.1263678

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (1996). Guided reading: Good first teaching for all children. Heinemann Press.

García, O., Flores, N., Seltzer, K., Li Wei, Otheguy, R., & Rosa, J. (2021). Rejecting abyssal thinking in the language and education of racialized bilinguals: A manifesto. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 18(3), 203-228. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2021.1935957

García, O., & Li Wei. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism, and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

García, O., & Kleifgen, J. A. (2019). Translanguaging and literacies. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(4), 553-571. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.286

Gonzalves, L. (2021). A system of erasure: State and federal education policies surrounding adult L2 learners with emergent literacy in california. In D. S. Warriner (Ed.), Refugee education across the lifespan (pp. 271-288). Springer.

Gottlieb, M. (2016). Assessing English language learners: Bridges to educational equity (2nd ed.). Corwin.

Lin, A. M. Y., & He, P. (2017). Translanguaging as dynamic activity flows in CLIL classrooms. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 16(4), 228-244. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2017.1328283

Parrish, B. (2019). Teaching adult English language learners: A practical introduction (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Pettitt, N., Gonzalves, L., Tarone, E., & Wall, T. (2021). Adult L2 writers with emergent literacy: Writing development and pedagogical considerations. Journal of Second Language Writing, 51 (Supplement 2021), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2021.100800

Schissel, J. L., De Korne, H., & López-Gopar, M. (2021). Grappling with translanguaging for teaching and assessment in culturally and linguistically diverse contexts: Teacher perspectives from Oaxaca, Mexico. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(3), 340-356. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1463965

Shohamy, E. (2011). Assessing multilingual competencies: Adopting construct valid assessment policies. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 418-429. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01210.x

Tammelin-Laine, T. & Martin, M. (2014). The simultaneous development of receptive skills in an orthographically transparent second language. Writing Systems Research, 7(1), 39-57. https://doi.org/10.1080/17586801.2014.943148

Turnbull, B. (2019). Translanguaging in the planning of academic and creative writing: A case of adult Japanese EFL learners. Bilingual Research Journal, 42(2), 232-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2019.1589603

Vega-Carrero, S., Pulido, M., & Ruiz-Gallego, N. E. (2017). Teaching English as a second language at a university in Colombia that uses virtual environments: A case study. Revista Electrónica Educare, 21(3), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.21-3.9