Using Flipgrid to facilitate an international virtual pen pal exchange provides learners with opportunities to gain and share cultural knowledge and experiences while engaging in authentic language tasks.

Keywords: Virtual exchange, pen pal, COVID-19, Flipgrid, cross-cultural communication, ELL

How can we connect students outside of the classroom? Pen pal exchange is not a new concept to language teachers and learners. This communicative exchange between learners reflects the essential role of interaction (Long, 1987) and sociocultural aspects (Donato, 1989; Lantolf, 1994) in learning. The development of technology in the 21st century has transformed communication between pen pals from handwritten letters to virtual exchange. International virtual pen pal exchange (IVPPE) allows learners to practice a language with native speakers, share authentic cultural experiences, and explore diverse cultural perspectives (O’Dowd, 2020; O’Rourke, 2007). This paper shares a collaborative virtual pen pal exchange project that engaged two cohorts of university students in intercultural communication on 12 topics via Flipgrid. We describe the project design, share our experiences and student feedback, and offer guidance to language educators with similar pedagogical interests.

Due to the disruption of in-person learning caused by COVID-19, the need for digital tools, such as virtual exchange, became more salient (Guillén et al., 2020). An IVPPE creates a community of learning. Thoughtfully-designed community learning has potential contributions toward students’ increased success, retention, and satisfaction (Greenfield et al., 2013). Adopting intercultural partners enables students in different countries to communicate beyond borders and to develop a feeling of social connectedness in remote settings (Bolliger & Inan, 2012; Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007). IVPPE has been adopted and researched in a wide range of teaching contexts. For instance, Catalano and Barriga (2021) examined their own experiences as teacher educators in the United States and Colombia, respectively, as they planned and facilitated a WhatsApp pen pal exchange meant to develop their teacher candidates’ intercultural competence. In an English as a Foreign Language (EFL) setting, Torres Beltrán and Santana Alarcón (2021) investigated 16 elementary school students’ writing skills development through a pen pal telecollaboration exchange. In Klimova’s (2021) study, the author shared the practice of integrating an IVPPE into online delivery in the Russian language program at the University of Pittsburgh. These studies highlighted that effective virtual exchange between students and their native-speaker partners pushed the learners and teachers out of their comfort zones and nurtured engagement in linguistic, intercultural, and technological learning experiences. Further, the exchanges compelled students to challenge their assumptions and reflect on their own identity and culture. Informed and inspired by the existing scholarship, we were dedicated to creating an interactive, impactful, and intercultural pen pal exchange for our students.

In our context as a university language department, we serve international students who are normally immersed in English language learning on our campus in the Midwestern United States. However, as a result of COVID-19, with some students confined to their home countries and some limited to activity within their dormitories, we began to provide programming virtually. It became clear that our first-year international students were facing a more complex level of uncertainty related to a new culture and different learning styles than those in the past due to COVID restrictions. It was important to offer them high-impact yet low-risk activities to support their transition. We felt the need to identify tools and (re)design lesson plans to foster community and engage students across countries and cultures (TESOL International Organization, 2022, The 6 principles section, no. 4). We created an IVPPE using Flipgrid to encourage “students’ active learning and integrative learning” in both language and culture (Lomicka, 2020, p. 307).

What is Flipgrid?

Flipgrid is an online video discussion platform that allows teachers to create a “grid” to invite students to upload short video responses to “topics” (i.e., prompts in audio, video, or text form) and reply to other students’ responses. Green and Green (2018) argue that Flipgrid supports discussion-based pedagogy and contributes to students’ critical thinking, minority students’ engagement in class, and the classroom culture. Stoszkowski (2018) examined how Flipgrid supported students’ social learning by discussing seven strengths of this app, namely (1) easy access, (2) convenience to record beyond the classroom, (3) encouraging participation, (4) video-based appeal, (5) more efficient formative feedback, (6) tracking engagement, and (7) compatibility with other platforms. Flipgrid has been increasingly adopted by language instructors over the past five years. When in-person learning was disrupted by COVID-19, Flipgrid became even more instrumental in facilitating engagement in virtual settings (Lomicka, 2020).

How did we use Flipgrid to engage students in cross-cultural communication?

What is described here was a collaborative project between two courses at our university. The first course, taught by the first author (Christensen), was part of the Intensive English Program (IEP) and was composed entirely of international students from mainland China. The course focused on developing learning strategies and study skills as well as connecting to the campus and community. The second course, taught by the second author (Kong), was an introduction to Chinese culture called Foreign Culture and Civilization (FLG). While most of the students in FLG were from the United States, there were also a few international students enrolled. Since the IEP students were devoted to improving their English proficiency, and the instructional language in the FLG course was English, the IVPPE was conducted in English.

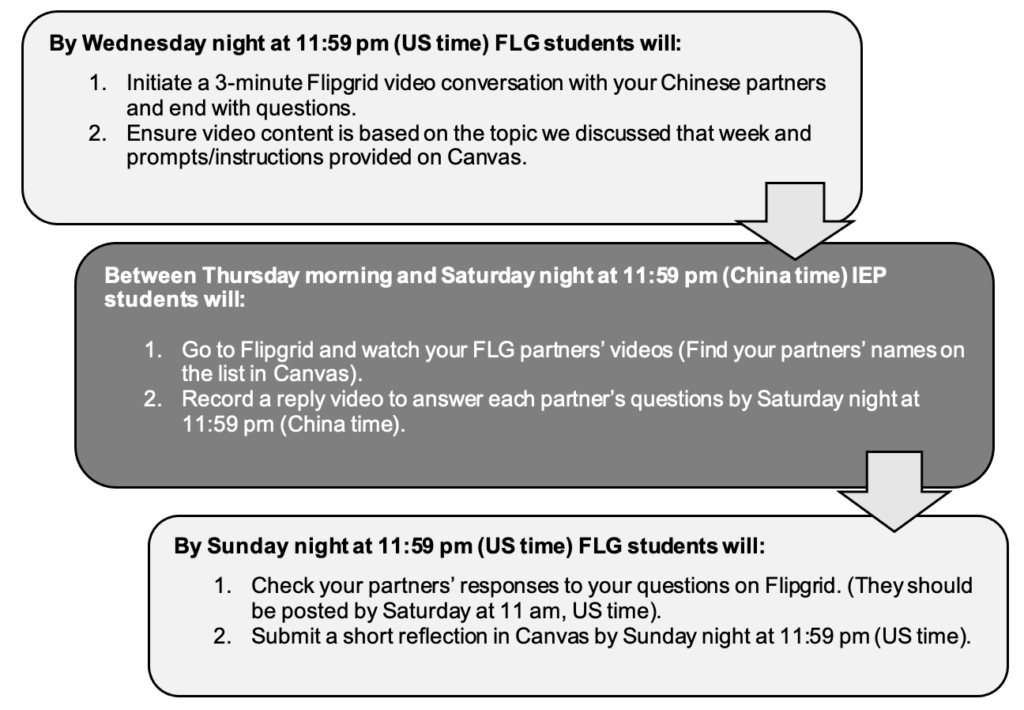

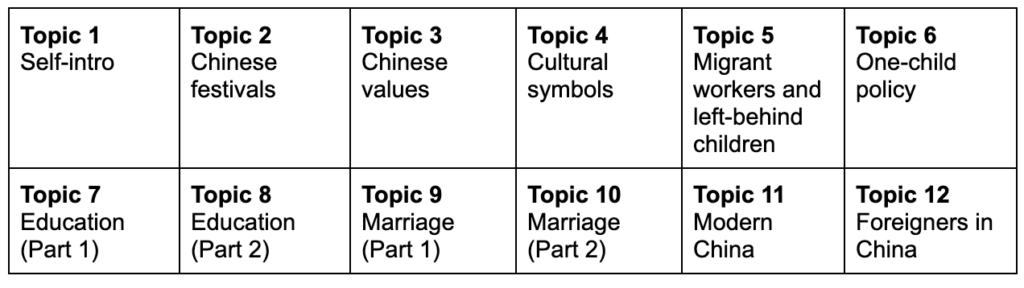

We intended this collaboration to create an opportunity for both cohorts to meet a peer from another culture and share intercultural experiences on given topics. In addition to cultivating intercultural understanding and empathy, the IEP students also received opportunities to practice the target language, English. Students from each course were randomly assigned several partners and kept the same partners throughout the semester. Students in the FLG course initiated weekly Flipgrid conversations by sharing what they learned from course materials and asking their peers questions. IEP students responded to FLG students’ posts and, as the course progressed, asked their own questions to their FLG partners (see Figure 1). There was no limit to how many responses or comment videos students could post. FLG students wrote weekly reflections and a final reflective paper on the exchange. While this practice was mainly formative, IEP students were required to write a reflection about their experiences twice during their course. Many students also opted to discuss it in other reflections when they could choose their topics. The criteria for this reflective writing focused on the depth of self-reflection, clarity of message, and staying on-topic. During the semester, both cohorts participated in 12 discussion topics (see Table 1).

What did the students say about virtual conversations?

At the beginning of the semester, IEP students confirmed that the pandemic was limiting their experiences: “because of the COVID, I can’t go outside to feel the American environment. So, I still know very little about America” (Jane, IEP student). Prior to the IVPPE, IEP students expressed an interest in learning more about U.S. culture: “I want to know more about the extracurricular life activities of American students and some traditional customs or habits. This will allow me to understand them better, have more common topics with them” (Harlan, IEP student). Some IEP students also saw an opportunity to improve their language abilities: “I want to improve my pronunciation and vocabulary from this experience. It is a good chance to improve my English and we can talk about different things each week. I can learn many new words” (Tony, IEP student). Students also mentioned wanting to know more about Americans’ impressions of Chinese culture: “I hope to learn about the differences between American and Chinese culture, and how young people in the United States view Chinese culture” (Kai, IEP student). The interaction with U.S. students that the IEP students hoped for in their initial comments came to be realized as the semester progressed.

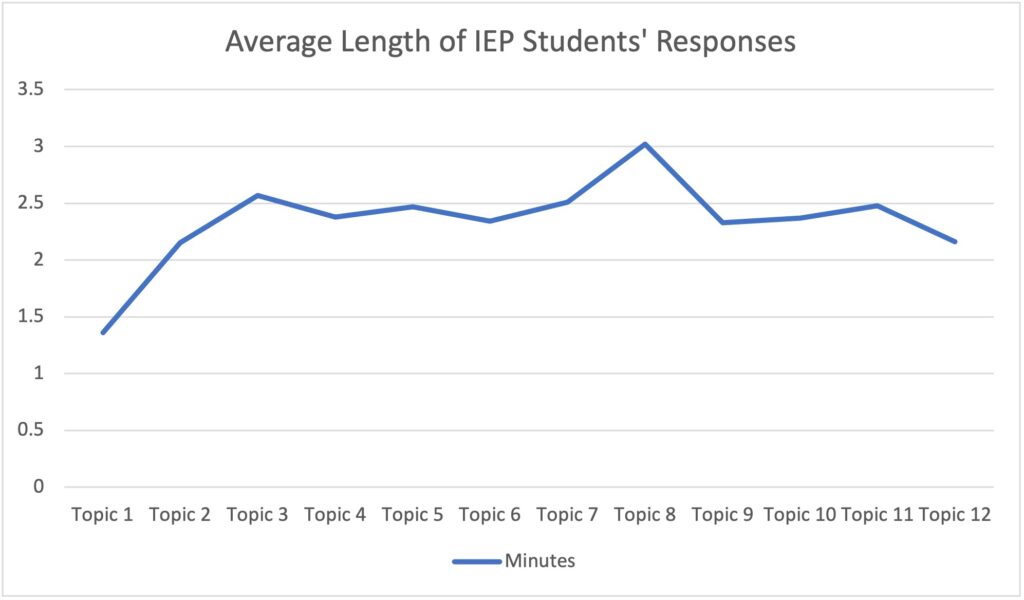

Although many of the subjects that students wanted to know more about were covered over the 12 weeks of our project (see Table 1), the topic about the Chinese education system prompted the longest average response from IEP students (see Figure 2). Since education was a very immediate and relatable issue for university students, students in both courses were especially curious and engaged in conversations on this topic: “For me, college life is just studying and entertainment, but I know that many American students need to do part-time jobs to pay for their tuition. They seem to attach great importance to getting an education because of their hard work” (Jane, IEP student). The second most popular topic was about Chinese cultural values. While students discussed differences between cultural values, many also expressed surprise at similarities: “When talking about values, most of my partners, like me, put filial piety first. This surprised me. I originally thought that most Americans regarded independence as very important and did not pay much attention to family; the reality is the opposite” (Harlan, IEP student).

By the middle of the course, the IEP students expressed a desire to continue speaking with their partners: “After chatting with them, I wanted to learn more about Americans . . . I like to watch the videos from my American partners who takes Chinese culture class. They share with me what they learned in class and some of their cultures, and I enjoy answering their questions and sharing some of my cultures with them” (Irene, IEP student). They also recognized linguistic benefits to the conversations: “One thing going well is that my listening is better than before” (Tony, IEP student).

Reflecting on the semester of exchanges between their partners, all IEP students reported that it was a positive experience for them. They mentioned how the conversations improved their listening and speaking abilities in English. “Last semester, I could not communicate a lot with my American friends because my English listening is very poor. Now, although I often get stuck on some complex words, I can have simple conversations with my American friends” (Johnny, IEP student). Students also shared additional benefits of their semester-long video conversations with FLG partners. “[This] was an invaluable opportunity to interact directly with peers in the United States . . . I have learned a lot from the American students. I believe such communication can play a great role in eliminating the barriers between cultures” (Lee, IEP student). In addition, several IEP students commented on how they appreciated their partners’ growing understanding of Chinese culture. “They have expressed a lot of their understanding of Chinese culture to me, and they have also shown me their love for Chinese culture” (Harlan, IEP student).

The IEP students valued the exchange a great deal, as evidenced by their comments above. However, their contribution to the success of the FLG students’ positive experience should not be overlooked. All the FLG students applauded their IEP partners’ support in not only broadening their cultural knowledge, but also in building a more ethnorelative view of other cultures. Some of the repeated themes in the FLG cohort’s reflections included: first-hand experiences and knowledge about China, building international friendships, challenging their stereotypes, and growing interest in visiting China. Many students also used specific examples to support their reflections. Mike (FLG student) wrote the following reflection after a unit on gaokao, China’s National College Entrance Examination:

Watching the videos [in class] on …[China’s] education system and learning about Gaokao was interesting but I was happy to hear about their personal experience from the exam for them to tell me how it was so I could understand better. Or the stereotype that all Chinese students do is just study constantly, where that may be the situation for some it isn’t for all of them. My pen pal partners opened my eyes about that as well explaining to me their own personal hobbies and what they like to do with their friends.

Dana (FLG student) also appreciated the first-hand knowledge gained from her pen pals. She shared, “I enjoyed getting a better insight on current day China as well as how it relates to my own generation being that my partners are the same age. It was fun getting real life examples and stories on what has happened in their own life, and I cannot wait to visit China one day.”

What are the benefits of having an international virtual pen pal?

It was apparent that using Flipgrid for this IVPPE provided abundant opportunities for the IEP students to extend language practice beyond the classroom. With a total of 565 responses, 17,861 views of videos, 1,340 comments, and 967.2 hours of engagement, there is no doubt that this project provided all students with far more opportunities for interaction than traditional face-to-face classes could provide. The IEP students were devoted to authentic intercultural communication (O’Dowd, 2020) during which they comprehended, manipulated, and produced language (Zhang & Luo, 2018). In other words, this IVPPE was able to “create conditions for language learning” (TESOL International Organization, 2022, The 6 principles section, no. 2) and public speaking in a low-risk and less stressful environment. Although Stoszkowski (2018) mentioned that one of the potential barriers to using Flipgrid is students’ concern about saying the right thing or showing their best work, we noticed that the feature of Flipgrid that allows students to record unlimited times until they are satisfied counteracted that concern. IEP students were able to share their best practice in the uploaded video, and this gradually enhanced their confidence. For English language students enrolled in online courses or studying in a place with few opportunities to speak English, utilizing Flipgrid for an IVPPE provides students with authentic language tasks and exposes them to language diversity.

An additional benefit of Flipgrid is that it automatically tracks the total number of responses, views, comments, and engagement on a topic. Data can be easily downloaded, and instructors can invite students to join using links or QR codes. Instructors can easily add a co-lead (partner instructor) who can edit groups/topics and approve responses and comments. These “tracking engagement” and “more efficient formative feedback” (Stoszkowski, 2018) features of Flipgrid made it easy for us to “monitor and assess student language development” (TESOL International Organization, 2022, The 6 principles section, no. 5). The two instructors in this project communicated on a regular basis to exchange observations of students’ participation, which was a contributing factor to the effectiveness of this project.

Additionally, this project allowed the IEP students to gain cultural knowledge through their peers, who were also learning from them. The feeling that they were not only learners but also experts in some areas helped them feel engaged within a cross-cultural community. At the beginning of the project, many IEP students shared their desires to learn more about U.S. culture, such as holiday celebrations and extracurricular life activities. By the end of the project, they cited many specific examples in their reflective writing to show their learning. Some noted that their views of U.S. culture became more complex and nuanced, evidence of challenging their assumptions (Guillén et al., 2020). They also felt the pride and joy of knowing their cross-cultural partners’ appreciation of Chinese culture. Similar results were discovered in Jin’s (2018) study about reflection on one’s own identity and culture through cross-cultural virtual exchange. This mutual learning opportunity was impactful and valuable, especially during difficult times when the pandemic and tension in the U.S.-China relationship caused increased anxiety and uncertainty.

What should I think about before starting an IVPPE?

In this paper, we described a collaborative project to connect two cohorts in an IVPPE using Flipgrid. Throughout the semester, both cohorts initiated and replied to videos on 12 topics. The statistics recorded in Flipgrid and students’ reflections presented linguistic and cultural benefits of virtual exchange. We had a positive experience using IVPPE, and it is our hope that this research-informed project will be adopted by colleagues with similar interests.

For those considering starting an IVPPE with Flipgrid, we offer the following reminders. First, participating in a virtual pen pal project is an engaging way to connect students from diverse classrooms and let them learn from each other. Speaking in front of a class as an individual can be intimidating, especially for shy students or English language learners. Recording a video allows students to think through what they want to say and present their thoughts and ideas without the added pressure of a live audience. English language learners also benefit from viewing videos multiple times to practice listening skills.

Second, to make virtual pen pal exchange effective, it is important for instructors to be thoughtful in creating relatable topics for students and facilitating an online community that allows the students and the instructor “to bond, develop a sense of trust, feel comfortable sharing information,” and to maintain “a sense of connectedness” (Lomicka, 2020, p. 306). It is worth mentioning that one of the drawbacks to using Flipgrid is that it is set up for students to access using Microsoft or Google accounts. If students do not have these accounts, an instructor must generate individual usernames and share them with students. It is important for instructors to provide the students with clear instructions on how to access and respond to topics. Instructors may also want to suggest minimum lengths for videos, especially for the first few exchanges. An additional challenge associated with this virtual pen pal project was the need for instructors to check and make sure students completed their videos. This was relatively easy to do using the search feature in Flipgrid.

Finally, we encourage instructors from any course to utilize Flipgrid intentionally and thoughtfully as a tool to increase engagement and connect their students with a wider community. Using Flipgrid to facilitate an international pen pal exchange provides learners with opportunities to gain and share cultural knowledge and experiences while participating in authentic language tasks.

References

Bolliger, D. U., & Inan, F. A. (2012). Development and validation of the online student connectedness survey (OSCS). International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(3), 41-65. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i3.1171

Catalano, T., & Muñoz Barriga, A. (2021). Shaping the teaching and learning of intercultural communication through virtual mobility. Intercultural Communication Education, 4(1), 75-89. https://doi.org/10.29140/ice.v4n1.443

Donato, R. (1989). Beyond group: A psycholinguistic rationale for collective activity in second language learning. Dissertation Abstracts International, 49(12), 3701-A.

Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. The Internet and Higher Learning, 10(3), 157-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2007.04.001

Green, T., & Green, J. (2018). Flipgrid: Adding voice and video to online discussions. TechTrends, 62(1), 128-130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-017-0241-x

Greenfield, G. M., Keup, J. R., & Gardner, J. N. (2013). New student orientation: Developing and sustaining successful first-year programs. Jossey-Bass.

Guillén, G., Sawin, T., & Avineri, N. (2020). Zooming out of the crisis: Language and human collaboration. Foreign Language Annals, 53(2), 320-328. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12459

Jin, L. (2018). Digital affordances on WeChat: Learning Chinese as a second language. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(1-2), 27-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1376687

Klimova, O. (2021). From blended learning to emergency remote and online teaching: Successes, challenges, and prospects of a Russian language program before and during the pandemic. Russian Language Journal, 71(2), 73-85. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rlj/vol71/iss2/5

Lantolf, J. P. (1994). Sociocultural theory and second language learning: Introduction to the special issue. The Modern Language Journal, 78(4), 418-420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02058.x

Lomicka, L. (2020). Creating and sustaining virtual language communities. Foreign Language Annals, 53(2), 306-313. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12456

Long, M. H. (1987). The experimental classroom. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 490, 97-109.

O’Dowd, R. (2020). A transnational model of virtual exchange for global citizenship education. Language Teaching, 53(4), 477-490. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444819000077

O’Rourke, B. (2007). Models of telecollaboration 1: eTandem. In R. O’Dowd (Ed.), Online intercultural exchange (pp. 41–61). Multilingual Matters.

Stoszkowski, J. (2018). Using Flipgrid to develop social learning. Compass: Journal of Learning and Teaching, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.21100/compass.v11i2.786

TESOL International Organization. (2022). The 6 principles for exemplary teaching of English learners. https://www.tesol.org/the-6-principles

Torres Beltrán, J. A., & Santana Alarcón, J. L. (2021). Developing young learners’ EFL writing skills through a pen pal telecollaboration exchange during the COVID-19 Pandemic in two rural institutions in Boyacá. Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, Tunja. http://repositorio.uptc.edu.co/handle/001/3814

Zhang, Y., & Luo, S. (2018). Teachers’ beliefs and practices of task-based language teaching in Chinese as a second language classrooms. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 41(3). 264-287. https://doi.org/10.1515/cjal-2018-0022