This article presents findings from an exploratory study with secondary English Language Development teachers using Language Pathways, a genre-based instructional tool, to increase students’ access to grade-level learning.

Key words: genre-based instruction, language awareness, Key Language Uses, teaching and learning cycle, functional language

As children learn the language of their families and communities, they develop an awareness of common patterns, or genres that facilitate how we use language every day to explain, argue, tell stories, or provide information to each other. Developing an understanding of how language functions allows speakers and listeners to quickly recognize and respond appropriately within their cultural and linguistic community (Bernstein, 1971; Bourdieu, 1991).

Schooling expands the everyday use of these genres by introducing complex grammatical structures, formality, and precise technical word choices as students explore new areas of academic study. High stakes assessments, state standards, and even curriculum often assume students have an awareness of how language functions in these genres. However, students for whom these genres are less familiar need explicit opportunities to examine and discuss these genres if they are to fully access, participate, and derive meaning during schooling in a new context (Gee, 2004; Hyland, 2007; Tung, 2013).

English language educators play a critical role in helping build students’ explicit knowledge of language. Educators can guide students in noticing the structures and language of a text. They can further support students in analyzing the text by discussing how grammatical and lexical choices work to shape meaning (Derewianka & Jones, 2016). Educators help students develop a stronger awareness of language through close examination of language features particular to the genre. This awareness helps students understand how language choices express and connect ideas, address audiences uniquely, and create cohesion within the genre (Humphrey, Droga, & Feez, 2013).

Developing Language Awareness

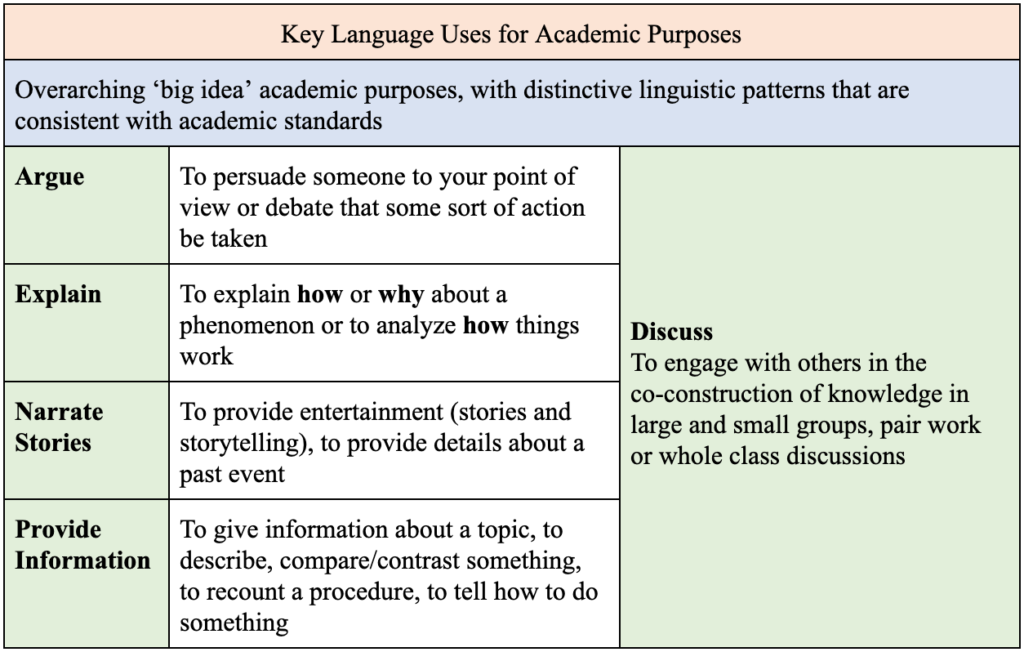

WIDA, at the Wisconsin Center for Educational Research, has been developing English language educator resources called Language Pathways, which are designed to engage teachers and students in language-rich discussions about academic genres. These resources draw on Halliday and Matthiessen’s (2014) view of language as a meaning-making system and the genre-based approach of Martin and Rose (2008), Christie (2005), and Derewianka and Jones (2016) that help make the language demands of school-based curriculum explicit. Language Pathways describe discourse patterns and grammatical features based on WIDA’s Key Language Uses: explaining, arguing, narrating stories, and providing information (see Table 1), so all students have the linguistic resources they need for school success.

Language Pathways follow the teaching and learning cycle (see Figure 1) developed for explicit language teaching in a genre-based approach (Derewianka & Jones, 2016; Martin & Rose, 2012; Rothery, 1994).

The teaching and learning cycle is a process for planning and guiding instruction that supports students’ language learning (Rose & Martin, 2012). Teachers guide students in noticing, deconstructing, and constructing oral, written, and visual messages. This allows students to explore language choices as a creative, authentic process for meaning-making (Derewianka & Jones, 2016). Language Pathways guide teachers through the teaching and learning cycle with resources designed to support language instruction at each phase of the cycle.

Language Pathways Pilot Study

A pilot study was conducted by WIDA to explore how teachers applied Language Pathways to their instruction. Twenty-five middle and high school English Language Development (ELD) teachers in a western, urban district participated in a two-year pilot study applying Language Pathways resources to their planning and classroom instruction using the teaching and learning cycle. The district focus for the year was to help students master an understanding of effective arguments, which was the language feature focused on in this study. Teachers participated in professional learning sessions, classroom observations with follow-up coaching, and monthly individual phone coaching, in addition to on-line and face-to-face learning communities.

In the following sections, four teachers demonstrate how they apply Language Pathways resources as they:

- plan for language instruction and assessment;

- build awareness of language patterns by deconstructing mentor texts;

- construct explicit features of the genre with their students; and

- facilitate self/peer feedback on independent writing

Paula: Planning for instruction and assessment

Paula works with 10th and 11th graders, many of whom are students with interrupted schooling. Paula created a unit plan template (see Figure 2) to help her focus on specific language features she wants students to recognize when reading and apply when writing independently. As a former language arts teacher, Paula often struggles with the distinction between ELA and ELD instruction.

“It’s been really difficult this year because the English teacher in me wants to come out and take over, but the key is to differentiate for students who are learning about language. The Pathways help me stay focused—bring it back to language.”

Her template helps her look deeper at how language features address or advance the purpose of the genre. For this unit, the key language use is argue. Paula downloads current event articles on fracking, mining, and alternative energy sources from Newsela, (www.newsela.com) to show how authors link ideas using causal, comparative, or sequential conjunctions to strengthen the argument.

David: Building awareness of language patterns through deconstructing mentor texts

David deconstructs mentor texts with his students as a way to point out and talk about language choices that authors make. Mentor texts, which exemplify patterns of language, provide opportunities for teachers and students to notice and analyze how meaning-making occurs. David is preparing his students for the reading of The Omnivore’s Dilemma (Pollan, 2006) in their 8th grade ELA class. He collects examples of persuasive language from newspapers, pamphlets, textbooks, and storybooks to deconstruct with students and show how arguments are constructed.

David builds awareness of the genre through conversations with students about how the author’s choices can influence readers’ thoughts and feelings. For example, David projects this sentence on the Smart Board:

Saving trashed food has become a matter of international urgency.

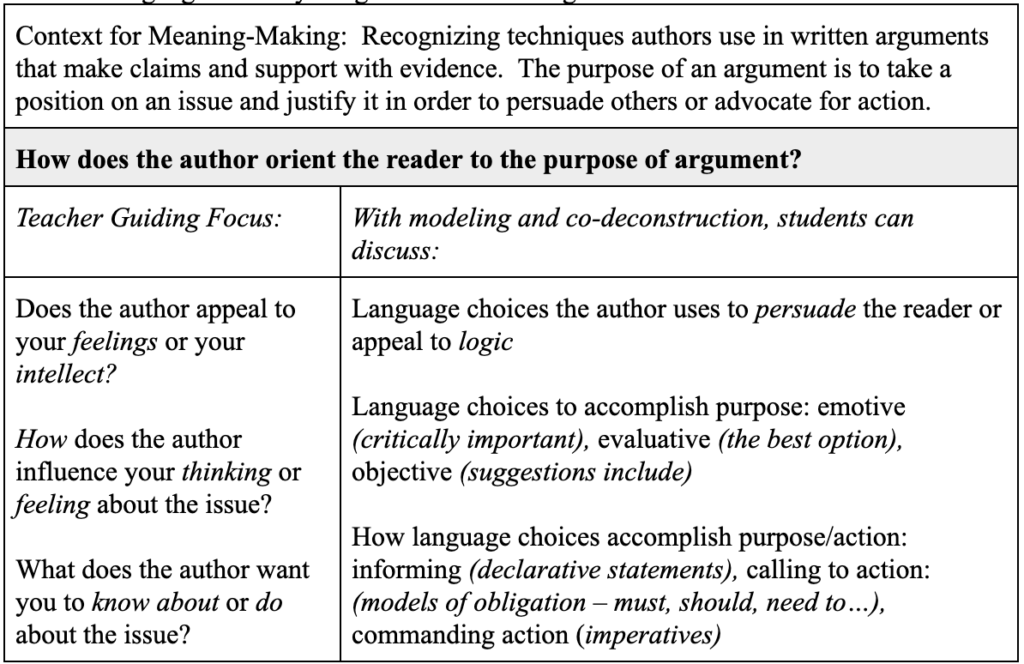

He asks students how they feel when they read it, what they think ‘trashed food’ might be, what the time frame for this urgency could be, who is “saving” and who might be impacted? David guides the discussion as they deconstruct the text. David uses Language Pathways tables to keep lessons focused on language. He feels this approach has re-energized his teaching and increased students’ motivation.

“We have interesting conversations about meaning. We go through the examples [text] together. I model how to break apart and look for the information from the chart [Language Pathways Argue] very explicitly.”

Table 2 is an example of the resource David uses to guide the conversation as he deconstructs and discusses texts with students.

Olivia: Joint construction of text

Olivia has 6th-8th grade newcomers. While her students have been formally schooled in their home countries, they are recent arrivals to the U.S. Olivia needs a mentor text that matches the cognitive maturity and academic skills of her students with their beginning English language proficiency. She hasn’t been able to find such texts, so she writes her own. She plans lessons around language features specific to the genre and adjusts her instructional timeline to provide the scaffolding her newcomers need, spending more time jointly constructing text. In this lesson, Olivia moves between deconstructing the mentor text and guiding the class to add details that strengthen claims.

Olivia gives students their own copy of the mentor text she has written while she projects a working copy on the screen. She reads, “American football is a dangerous sport. Many players are hurt every year.” Using both English and Spanish, Olivia points out the claim. Students talk about how the opinion is stated like a fact to make it sound more credible. Olivia highlights the rationale. She engages students in a conversation about the strength of the rationale.

“Do we really know if this sport is dangerous? How many players are hurt? What are the injuries? Where does the information come from?”

She challenges them to look for the evidence in the text. She shows them another statement:

“2,000 football players are hurt with concussions every year.”

Together, they highlight text that answers “how many, what kind, what type?” and talk about how quantity, quality, and descriptive details strengthen a claim. Olivia brings students’ attention to how noun phrases can be expanded to add details and writes examples on a classroom chart (see Figure 3).

Jerome: Independent construction and evaluation of the genre

Jerome is a first-year high school teacher. He has advanced students who are anxious to exit ELD classes but must pass a writing assessment before they can exit. Jerome is struggling with his class; the students are not feeling successful. Jerome is finding that the school-wide rubric doesn’t reflect the language lessons he’s been teaching.

“I want my students to be able to recognize and produce good arguments. I teach my students how to look at how authors’ decisions impact purpose, strength, and cohesion of an argument and I want students to think about their own language choices when writing their arguments. The school-wide rubric doesn’t even acknowledge these critical elements [of cohesion]. I also want students to be able to reflect on their work—what they’ve done well and where they can improve.”

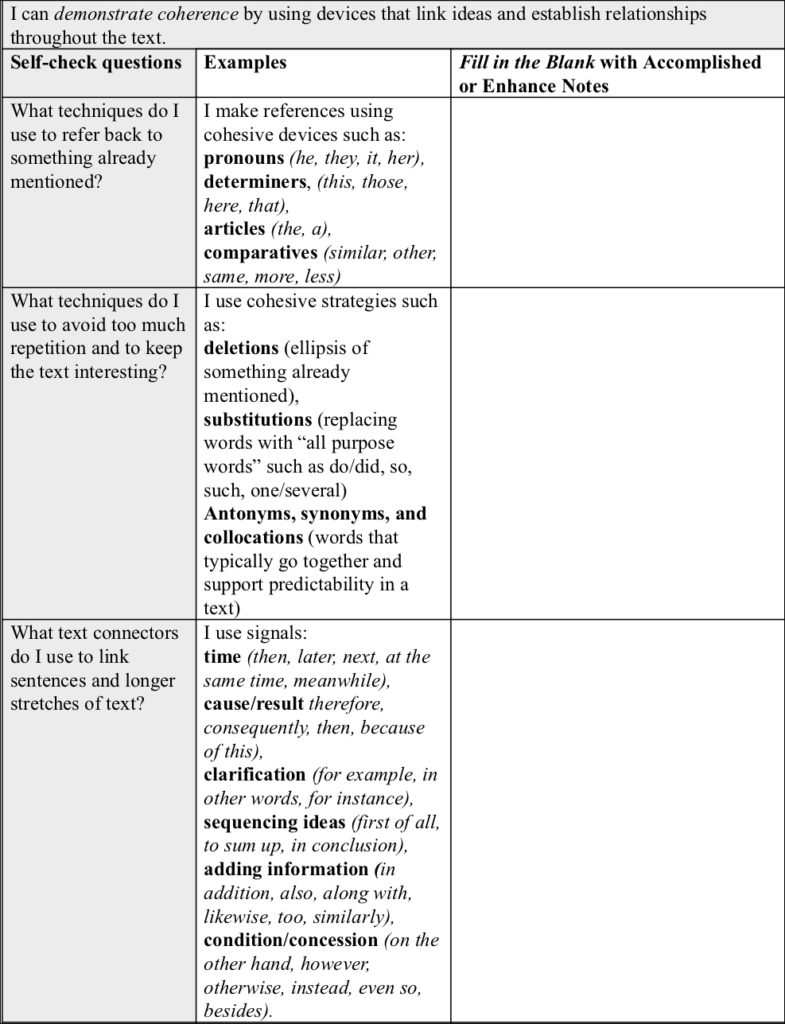

Jerome designed a formative assessment tool (see Table 3) that could serve as self-reflection or peer reflection prior to teacher evaluation. He narrowed the evaluative focus based on lessons taught using Language Pathways writing resources. Jerome found that the rubric encouraged students to recognize their writing accomplishments. This also helped to keep peer suggestions for improvement connected to meaning-making. Students examined how well the writer’s message accomplished the task. As a result, students felt more confident about their writing, were more willing to engage in reflective discussions about their writing and complete multiple edits.

Summary

Meaning-making reflects cultural communities and defines how language is used particularly in schooling. Building multilingual students’ awareness about academic genres and language choices related to those genres is essential as we strive for educational equity. Teachers in this study made changes in their language instruction, but they also developed greater personal awareness about language. As one teacher remarked, “I’m so much more aware of language. You have to break it [language] apart—deconstruct to see what’s happening. Share that with kids.”

As language teachers, we advocate for our students but we also advocate with our students. By demystifying the cultural aspects of language, academic language in particular, we afford our students greater voice and agency in their own learning. Sharing how meaning-making occurs through joint deconstruction and construction of text, we allow multilingual learners to accomplish their communicative goals in school and community settings. Reflecting on the study experience, a teacher shared, “The Pathways are an answer that I’ve been looking for as a social activist… critical awareness for the students with little access to school language.”

References

Bernstein, B. (1971). Class, codes, and control: Theoretical studies towards a sociology of language. New York: Schocken Books.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. (Translation by G. Raymondson & M. Adamson). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Christie, F. (2005). Language education in the primary years. Sydney: University of NSW Press.

Derewianka, B., & Jones, P. (2016). Teaching language in context. Victoria, AU: Oxford Press.

Gee, J. P. (2004). Situated language and learning: A critique of traditional schooling. New York: Routledge.

Halliday, M., & Matthiessen, C. (2014). Introduction to functional grammar (4th ed.). New York: Routledge.

Humphrey, S., Droga, L., & Feez, S. (2013). Grammar and meaning. Newtown, NSW, AU: PETAA.

Hyland, K. (2007). Genre pedagogy: Language, literacy and L2 writing instruction. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16(3), 148-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2007.07.005

Martin, J., & Rose, D. (2008). Genre relations: Mapping culture. London: Equinox Publishing.

Pollan, M. (2006). The omnivore’s dilemma. New York: Penguin Press.

Rose, D., & Martin, J. (2012). Learning to write, reading to learn. South Yorkshire, UK: Equinox.

Tung, R. (2013). Innovations in educational equity for English language learners. Voices in Urban Education, 37, 2-5.