Translingual content-integrated literature curricula can provide ESL/EFL learners with acquisitional, metalinguistic, and affective benefits. Haiku, the compact Japanese verse form, may be an ideal choice of literary genre to integrate in this way, due to its clarity and simplicity.

Keywords: Literature, Translanguaging, Haiku, SLA, Literacy

Throughout history, scholars have argued for the educational value of literature. To the philosopher Kongzi (孔子), better known in the West as Confucius, poetry was morally edifying and taught a sense of social duty. Some 25 centuries later, Canadian literary theorist Northrup Frye proposed that literature’s subjectivity pushes learners to develop critical and creative habits of mind (Frye, 1964). English as a second/foreign language (ESL/EFL) educators have valued literature as authentic source material and noted how its emotional themes inspire student participation and investment (Daskalovska & Dimova, 2012). However, in my experience, many instructors avoid using literature for fear of not being qualified, or of students not being advanced enough to handle the ‘literary’ register.

This paper will make a case for pedagogic translingualism—which is the limited introduction of students’ first language (L1) into the second language (L2) classroom—as a tool to put literary texts within the reach of students at any level of English competence. Furthermore, I will argue that the use of haiku, the traditional Japanese verse form, amplifies this advantage because it delivers all the affective power of sophisticated literature, but with brevity and directness of expression that make it an ideal entry-point, not just for students with limited English vocabulary, but also for ESL teachers who are curious about literature and want to experiment with using it in their classrooms.

What is pedagogic translingualism?

Perhaps as a consequence of both rapid globalization and the demographic growth of multiethnic polities in the West (Duarte, 2020), language education in recent decades has become strongly concerned with multilingualism (May, 2014), a phenomenon which has been described under a multitude of names: bilingualism, multilingualism, translingualism, translanguaging, code-switching, code-mixing, etc. For our purposes, translingualism will do.

Translingual research has examined a variety of phenomena, from multilingual interlocutors’ apparently natural tendency to mix their codes freely during conversation, to policy-driven sociolinguistic questions about language rights in education, to issues of how L1 ability and use might influence L2 acquisition and learning (Butzkamm & Caldwell, 2009). It is the latter area which is relevant here. Building on Cummins’ (1979) interdependence hypothesis, which suggests that greater mastery of the L1 may facilitate subsequent mastery of the L2, especially in the realm of literacy, pedagogic translingualism proposes that space be set aside within the L2 classroom for the use of student L1 (Cook, 2010; MacSwan, 2020).

Benefits of pedagogic translingualism

Pedagogic translingualism is said to underwrite efficient vocabulary acquisition (Lee & Macaro, 2013), help develop metalinguistic awareness (de la Campa & Nassaji, 2009), and increase affective investment in the classroom (Ellwood, 2008). This final effect may originate in a sense of validation some learners report feeling when their ethnolinguistic identity is recognized (Huang, 2010). Furthermore, vocabulary acquisition and metalinguistic awareness are of great relevance to students with low literacy levels in their L1, who are more likely than their peers to face difficulty developing these features of L2 literacy (Bigelow & Tarone, 2004). As such, ESL programs interested in building English literacy among L1 pre-literate learners may have particular reason to explore pedagogic translingualism.

Literature for language teaching

The reasons for incorporating literature into an ESL syllabus are not always obvious. Scholars have argued that pragmatic pedagogic concerns have “marginalized” literature (Deng, 2006, p. 62), and that fashions in the humanities have elevated sociocultural commentary at the expense of artistic expression (Abbs, 1994). In the words of Yin Qiping and Chen Shubo of China’s storied Zhejiang University, literature is often dismissed as a “…soft option, an indulgence or mere trimming to decorate the hard center of the market-oriented syllabus,” a mistake they call “corrosive” to English teaching in China, the West, and beyond (Yin & Chen, 2002, p. 318).

Benefits of literature for language teaching

ESL learners may derive several advantages from the teaching of literature; it constitutes a valuable resource of authentic L2 material, provides an efficient tool for constructing linguistic competence, and fosters student participation through affective engagement.

First, literary texts are authentic, which is to say texts produced for communicative purposes within a given speech community are said to be preferable to texts merely produced for the purpose of language teaching, as they may provide a more accurate model for cultural and linguistic learning (Aladini & Farahbod, 2020). Next, evidence for literature’s utility in developing student linguistic competence has been attested to in domains of fluency and accuracy (Babaee & Yahya, 2014), in all four of the ‘macro’ skills of reading, writing, speaking, and listening (Shazu, 2014), and at various levels of linguistic awareness: lexical, syntactic, discoursal, and metalinguistic (Bibby & McIlroy, 2013). Third, literature can inspire student investment and participation. Simply put, many learners find poetry and storytelling more affectively engaging than exclusively linguistic instruction (Mason & Krashen, 2004; Vural, 2013). One study found the incorporation of English poetry in an ESL course led 72% of learners to report an increased sense of their own expressiveness in English, and 83% to report sensations of joy and freedom associated with the poetry activity (Liao, 2018).

Haiku for ESL classes

If literary texts generally have value for ESL classrooms, then haiku—the famous miniaturized Japanese verse form—has, I will argue, a particular use for teachers who are new to using literature in language teaching, and also for low/intermediate ESL students (especially those with reading struggles). In both cases, it is the clarity and brevity of haiku that makes it ideal. According to Atsushi Iida, haiku offers learners of all backgrounds “opportunities to develop their language proficiency while giving them chances for self-discovery” (2010, p. 61). The pedagogic utility of haiku stems in part from how its minimal form incentivizes direct expression. While many students (and, sadly, teachers) mistakenly believe that poetry requires a sophisticated command of obscure vocabulary (Liao, 2018), haiku’s simplicity makes it useful even for students with beginner-level English skills. A haiku can be read in a matter of seconds, and its pithy nature virtually guarantees that students will not get lost searching for the author’s meaning—a fear that may prevent English instructors from wading into the sometimes-cloudy waters of literature. In sum, haiku are so brief, so concentrated (often a mere seventeen syllables in Japanese) that they allow even very low proficiency learners to experience the advantages of literature in ESL.

From sandwiches to the stars: A curricular guide

The following is a rough guide to designing a content-integrated translingual ESL unit using haiku poetry. It takes advantage of literature’s capacity to inspire student affective investment, haiku’s potential to ease cognitive burdens on both low-literacy students and teachers who are new to literature, and the affective and vocabulary-building benefits of pedagogic translingualism. Furthermore, haiku also presents teachers with an opportunity to build multicultural learning into the ESL classroom. The unprecedented global popularity that Japanese animated films have achieved in recent years (Garcia, 2013) may increase student interest in haiku coursework even beyond the bonus translingualism and the arts already impart.

Finding the perfect haiku

Curious ESL instructors are invited to begin designing their translingual literature lesson by searching for haiku at the library or on the internet. Good poetry produces kinesthetic reactions; you’ll know you’ve found gold when you smile, feel goosebumps, or choke up a little. One can hardly miss, however, with the following poets, all of whom can be found in Haiku: An Anthology of Japanese Poets (Addiss et al., 2009). Kobayashi Issa (1763–1828) describes human emotional and psychological states with pathos and humor.

All the time I pray to Buddha

I keep on

killing mosquitoes

Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902) wrote in a modern style that is sharply observational and realistic.

Pruning a rose

sound of scissors

on a bright May day

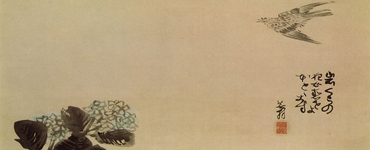

Matsuo Basho (1644-1694) shows the natural world in sublime detail, as in the following verse, which is very famous in Japan:

A day of quiet gladness,—

Mount Fuji is veiled

In misty rain

These are merely a few of the most famous haiku writers, as a cursory search will reveal.

Multilingual sandwiches

Once you’ve identified a few works of haiku, begin considering your assessment and activities. Celic and Seltzer’s (2011) Translanguaging: A CUNY-NSIEB Guide for Educators provides numerous suggestions for creating unit-level translingual assessments and activities. For example, the Multilingual Collaborative Work: Reading Groups heading (p. 68), advises the ‘Read in English & Discuss in Any Language’ strategy. In this approach, students are given an English text to examine and work in small groups to answer comprehension questions and discuss the meaning of the text using English, their L1, or mixed code. In short, give your learners English materials and questions to discuss, but allow the discussion itself to drift into multiple languages, if the students find it useful. After the students have checked their understanding with one another, and brainstormed in their language of choice, they must produce output in English. Starting with English input and ending with English output provides ample opportunity for target language practice, but the L1-friendly stage in the middle allows students to check comprehension, be certain everyone understands the goal of the activity, and take advantage of the more sophisticated vocabulary and syntax for abstract thought (especially relevant for arts curricula) which they likely possess in their home language (Butzkamm & Caldwell, 2009). This staple of translingual coursework has been called the ‘sandwich activity,’ because the L1, once strictly banned from ESL, has found a place in the center of the process, neatly pressed between L2 input and L2 output (Cook, 2010).

The star diagram

But what exactly about the haiku will students discuss? One useful device for answering this question is Collie and Slater’s ‘star diagram’ (1990, p. 101).

Draw a large five-pointed star on a sheet of blank paper, then label the points of the star with conceptual or sensory touchstones, such as “(what do you) see and hear,” “(what do you) smell, taste and feel,” “what motion/kinesthetics take place,” “what emotions do you feel,” and “what do you think poet is trying to say?” Students may fill the page by writing their impressions (again, in their L1, English, or mixed code), or simply use the ‘points of the star’ to trigger oral responses in their small groups. Other options, especially when reading authentic Japanese haiku, include categories like “the natural world,” “truths about the human experience,” and “references to the seasons,” all of which feature prominently in haiku poetics. You can, of course, choose your own concepts for the five points of the star.

Writing their own haiku

A writing or speaking class may even go further, asking students to compose their own haiku in response to the readings. Since Japanese haiku have strict formal rules that may be less relevant in English (17 syllables broken into lines of five, seven, and five, for example), teachers may instead choose to assign their students what the novelist and poet Jack Kerouac defined as ‘Western haiku’: short poems that “say a lot in three lines” (Weinreich, 2003, p. x).

Kerouac, perhaps best known as a popularizer of the ‘Beat Generation,’ elaborated on Western haiku, suggesting they ought to be “airy and graceful” and also “very simple and free of any poetic trickery” (Weinreich, 2003, p. x). Nearly a century earlier, Masaoka Shiki had also emphasized simplicity, offering this advice to young haiku poets: “Take your materials from what is around you—if you see a dandelion, write about it; if it’s misty, write about the mist. The materials for poetry are all around you in profusion” (Trumbull, 2016, p. 101). ESL instructors interested in helping students experiment with creative writing through the haiku form could do worse than to follow Shiki and Kerouac’s guidelines.

Summary

The title of this article is one of Kerouac’s poems; it demonstrates the attention to detail, simplicity, and instantaneity of haiku at its best, an art form which encourages us to look closely at the natural world and to find personal significance in it, as does Prince Otsu in his famous meditation on impermanence, written shortly before his death (Addiss et al., 2009):

Today, catching sight of the mallards

crying over Lake Iware;

must I, too, vanish from this world?

Personal significance is also a major reason for literature’s utility in ESL. Literary curricula utilize authentic materials to foster affective engagement and linguistic competence, while translingual activities like the ‘sandwich’ legitimize learners’ L1, create emotional significance, and provide opportunity for efficient building of vocabulary and metalinguistic awareness. Instructors may try a brief translingual content-integrated haiku activity to get their toes wet in Kerouac’s birdbath, while those with more experience using the arts in ESL may prefer to design a full unit, leaping fully, like summer swimmers, into Prince Otsu’s vast and mallard-flown Lake Iware, so to speak. Either way, students and instructors both have much to gain from diving deeply into the translingual uses of literature.

More materials can be found at the following sites:

www.thehaikufoundation.org

www.hsa-haiku.org

https://atsushi-iida.com/research/publication/

References

Abbs, P. (1994). The educational imperative. Falmer Press.

Addiss, S., Yamamoto, F., & Yamamoto, A. (2009). Haiku: An anthology of Japanese poems. Shambhala.

Aladini, F., & Farahbod, F. (2020). Using a unique and long forgotten authentic material in the ESL classroom: Poetry. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 10(1), 83-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1001.12

Babaee, R., & Yahya, W.R.B.W. (2014). Significance of literature in foreign language teaching. International Education Studies, 7(4), 80-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n4p80

Bibby, S., & McIlroy, T. (2013). Literature in language teaching: What, why, and how. The Language Teacher, 37(5), 19-21. Retrievable from https://jalt-publications.org/

Bigelow, M., & Tarone, E. (2004). The role of literacy level in second language acquisition: Doesn’t who we study determine what we know? TESOL Quarterly, 38(4), 689-700. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588285

Butzkamm, W., & Caldwell, J. (2009). The bilingual reform: A paradigm shift in foreign language teaching. Narr Studienbucher.

Celic, C., & Seltzer, K. (2011). Translanguaging: A CUNY-NYSIEB guide for educators. City of New York University Press.

Collie, J., & Slater S. (1990). Literature in the language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Cook, G. (2010). Translation in language teaching. Oxford University Press.

Cummins, J. (1979). Linguistic interdependence and the education of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research, 49(2), 222-251. https://doi.org/10.2307/1169960

Daskalovska, N., & Dimova, V. (2012). Why should literature be used in the language classroom? Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 1182-1186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.271

de la Campa, J., & Nassaji, H. (2009). The amount, purpose, and reason for using L1 in L2 classrooms. Foreign Language Annals, 42(4), 742-759. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2009.01052.x

Deng, T.Z. (2006). Ecocritical approach to English literature in a Chinese context. CELEA Journal, 29(6), 62-68.

Duarte, J. (2020). Translanguaging in the context of mainstream multilingual education. International Journal of Multilingualism, 17(2), 232-247. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2018.1512607

Ellwood, C. (2008). Questions of classroom identity: What can be learned from codeswitching in classroom peer group talk? The Modern Language Journal, 92(4), 538-557. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00786.x

Frye, N. (1964). The educated imagination. Indiana University Press.

Garcia, J. (2013). The rise in popularity of Japanese culture with American youth: Causes of the “cool Japan” phenomenon. Japan Studies Review, 17, 121-140.

Iida, A. (2010). Implications for teaching haiku in ESL and EFL contexts. The Language Teacher, 34(3). Retrievable from https://jalt-publications.org/

Lee, J.H., & Macaro, E. (2013). Investigating age in the use of L1 or English-only instruction: Vocabulary acquisition by EFL learners. The Modern Language Journal, 97(4), 887-901. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12044.x

Liao, F.Y. (2018). Prospective EFL teachers’ perceptions towards writing poetry in a second language: Difficulty, value, emotion, and attitude. Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.32601/ejal.460583

MacSwan, J. (2020). Translanguage, language ontology, and civil rights. World Englishes, 39(2), 321-333. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12464

Mason B., & Krashen, S. (2004). Is form-focused vocabulary instruction worthwhile? RELC Journal, 35(2), 179-185. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368820403500206

May, S. (Ed.). (2014). The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and bilingual education. Routledge.

Shazu, R. I. (2014). Use of literature in language teaching and learning: A critical assessment. Journal of Education and Practice, 5(7), 29-35.

Trumbull, C. (2016). Masaoka Shiki and the origins of shasei. Juxtapositions, 2(1), 87-122.

Vural, H. (2013). Use of literature to enhance motivation in ELT classes. Melvana International Journal of Education, 3(4), 15-23.

Weinreich, R. (Ed.). (2003). Jack Kerouac: Book of haikus. Penguin.

Yin, Q., & Chen, S. (2002). Teaching English literature in China: Importance, problems, and countermeasures. World Englishes, 21(2), 317-324. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-971X.00251