Christina Torres & Carmen Toscano-Fuentes

This article describes the research-informed design and implementation of an online, multimodal, multiliteracies activity used in a teacher-training telecollaboration exchange between a U.S. and a Spanish university. Qualitative findings from student-provided feedback are provided.

Keywords: teacher education, multiliteracies, learning by design, English as a foreign language (EFL), English as a second language (ESL)

Multiliteracies for teacher training

A large-scale discussion about what it means to be literate has blossomed since the New London Group (NLG) (1996) began a conversation on multiliteracies. Inspired by the challenges presented to educators at a turning point in technology access and an increasingly interconnected world, the NLG authors questioned the traditional definition of literacy––to read and write a standard national form of a language. Multiliteracies pedagogy acknowledges that there are multiple modes of communication beyond print text (such as visual, spatial, and gestural modes), and that life experiences that learners bring to their educational contexts are an important element in meaning-making.

While reading and writing in a standardized form of a national language still carries importance, active participation in the complexities of present day meaning-making often requires a more nuanced approach to literacy (Kalantzis & Cope, 2023; New London Group, 1996). Additionally, Learning by Design (LbD) provides a pedagogical repertoire for instruction using a multiliteracies approach (Fernandes, 2023; Kalantzis et al., 2005; Kalantzis & Cope, 2025). Multimodal reader-viewership, a valuable aspect of teacher training, is a skill that goes beyond decoding words and includes active reflections about a text’s connections to readers’ life experiences, recognizing and using different genres for different purposes, and understanding social contexts of texts (Fernandes, 2023). Training examples can be helpful for practitioners to conceptualize how to apply multiliteracies into their own pedagogical repertoire. This article illustrates one approach to develop multimodal reader-viewership in English language teacher training. The theoretical frameworks for the multimodal reader-viewer activity design and qualitative analysis of student feedback are multiliteracies and LbD (e.g., Kalantzis & Cope, 2025; Zapata, 2022).

Methodology

The discussion activity featured in this article was part of a larger project that connects two programs through telecollaboration and service-learning as part of training English language educators. The partner classrooms included: (1) a group of students from a large southeastern U.S. university enrolled in a Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (MA TESOL) program and a graduate-level certificate in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL), and (2) a group of students from a public Spanish university in western Andalusia completing their Título de Máster (Estudio de Postgrado) as part of their teacher preparation for secondary education, vocational training, and English courses at official language institutes throughout Spain. The discussion activity served as an opportunity for both groups to apply multimodal reader-viewership and promote intercultural communication through an icebreaker. The participants provided informed consent for their discussion and reflection data to be used. Participants were de-identified and data kept securely in a repository data and was approved by the U.S. university’s Institutional Review Board (#00007413).

Twenty-five graduate students from two universities participated in the discussion activity described here. Participants included students from a southeastern U.S. university, four in a Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (MA TESOL) program, and two in a graduate-level certificate program in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL). Nineteen of the participants were students from a public Spanish university in Andalusia completing their Título de Máster (Estudio de Postgrado) as teacher preparation.

After completion of the activity, fifteen students submitted anonymous open-response answers to a Qualtrics survey answering the question: Please share what your experience was like with the multimodal reader-viewer discussion activity. Your thoughts about the activity are appreciated. All responses are anonymous. Generic qualitative coding (Saldaña, 2021) was used to identify themes related to the students’ experiences with the discussion.

Inspiration for activity design

Approaches to LbD in Zapata (2022) and Fernandes (2023) were particularly influential in the design of the discussion activity in this article. Zapata (2022) provided recommendations for how to guide students through LbD knowledge processes, such as first experiencing the known and then the new. Fernandes’ (2023) example from her English as a Foreign Language course in Brazil used a cartoon image with a common Portuguese expression translated as “Don’t stick your spoon in a husband and wife’s argument” as a point of reflection with the accompanying cartoon showing a spoon protecting a woman and her child from an aggressive man. Fernandes began classroom discussion with experiencing the known, as students were aware of the common phrase. It then moved into experiencing the new and analyzing functionally (through closely inspecting the image and how they derived meaning) and critically (by reflecting on the context for the saying in the first place). Notable differences between Fernandes’ discussion and the activity featured in this article are the inclusion of music and the online context.

Preparing students for the activity

The discussion activity served as an opportunity to apply multimodal reader-viewership and promote intercultural communication. Students prepared for this discussion activity by individually completing an online module containing a multimedia presentation that modeled multimodal reader-viewership using the phrase “water under the bridge” accompanied by an image* with trash floating in water to reference environmental issues (see Figure 1).

After completing the online training module, which included an explanation of multiliteracies and LbD, students practiced their multimodal reader-viewer skills through the theme of self-empowerment. A guided self-reflection included a common expression in combination with images and questions about the phrase. These preparation activities readied students for the main discussion activity. The discussion prompt included a flamenco song excerpt with empowering lyrics. It encouraged students to share their own ideas of familiar songs that embody a similar meaning in a language of their choice. Students connected these songs to relevant images and explained their relevance.

The flamenco-inspired discussion and activity design

Guided reflection

A flamenco song lyric was selected as an opportunity for cross-cultural discussion between Spanish students and U.S. students (including U.S. citizens and international students). Flamenco is relevant in discussions of empowerment because analysis of traditional lyrics has revealed chauvinist themes such as love as the metaphorical death of a man and the idea of a woman as “bad” because loving her causes a man pain (Fonseca-Mora & Camacho-Diaz, 2022). Artists like Rocío Márquez are now reimagining lyrics to flamenco songs to have a more empowering lens while keeping the traditional musical style. Therefore, lyrics from Agüita de Cielo by Márquez were used.

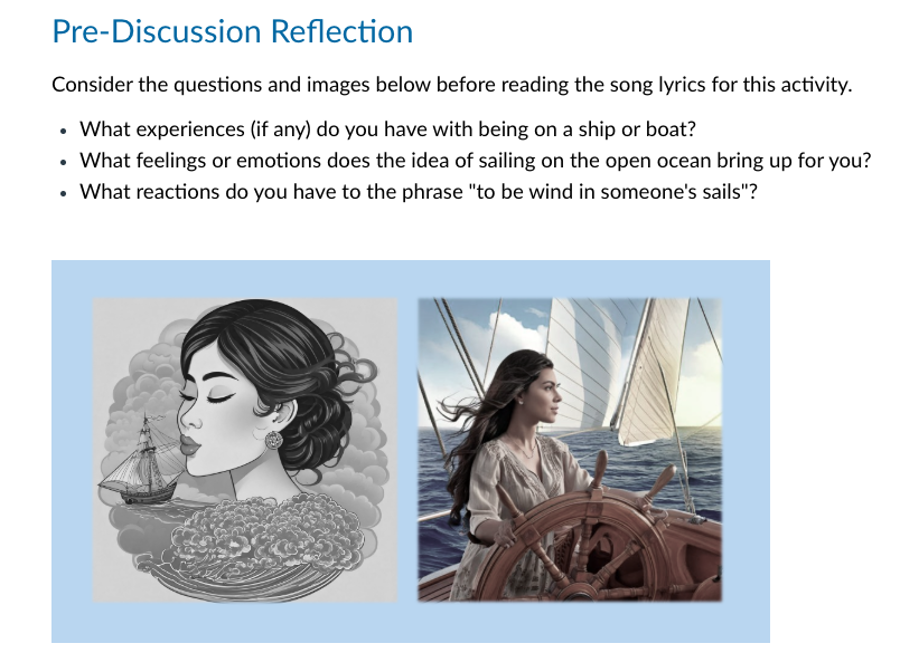

Figure 2 shows the Adobe Firefly AI generated images used with the phrase “to be wind in someone’s sails” and questions to activate prior knowledge (experiencing the known) and begin to explore the embodied reactions (analyzing functionally and critically) to the phrase and images.

Next, a stanza of the original lyrics in Spanish and an English translation (see Table 1) were provided for students followed by a YouTube clip of Márquez performing the song.

Song and image selection

After reflecting on the images, reading the lyrics, and watching the song excerpt, the students reflected on the authors’ intentions with the song and how personal experience (lifeworlds) may influence interpretation of the lyrics. Context about the new empowering lens in the flamenco lyrics was provided for students in an accompanying paragraph.

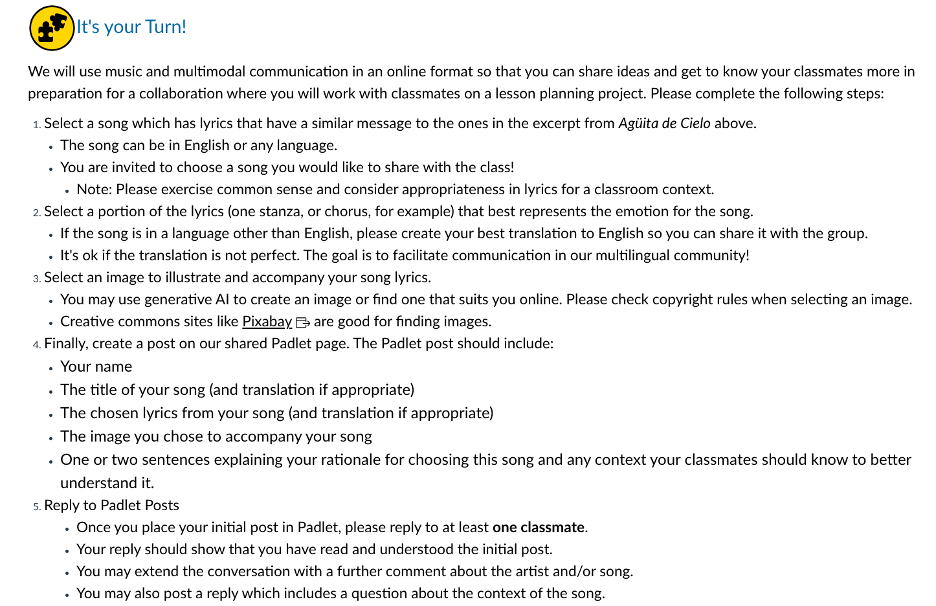

The students were then invited to choose a song in English or any other language which shared a similar message to “Agüita de Cielo.” They then selected a portion of the song to share with the class, translated this to English as a common language (if needed), and chose an image connecting to the song lyrics they selected.

Table 1. Song Lyrics Excerpt

| Original | English Translation |

| Agüita de Cielo

Para que soplen tus velas Yo no soy viento de nadie Para que soplen tus velas Que para aguantar temporales, Visto mi barca de seda Y que navegue a su aire |

Water Droplets from the Sky

If you’re looking for someone to be the wind in your sails, I am not anyone’s wind. If you’re looking for someone to be the wind in your sails, to put up with storms, I’ve readied my ship to navigate where the wind takes it |

-Rocío Márquez

Engaging in the discussion

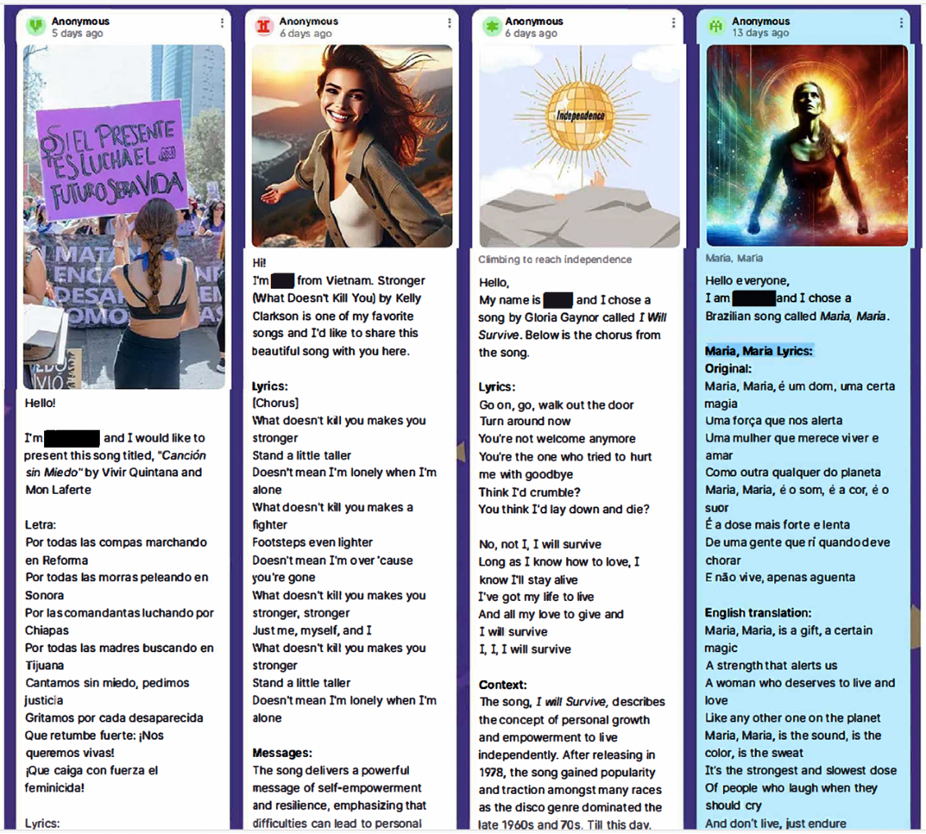

Students crafted a post on a shared Padlet page explaining the connection between the image, song lyrics, and the flamenco stanza that inspired the discussion. Figure 3 illustrates the instructions given to the students for this discussion.

Students and their song choices

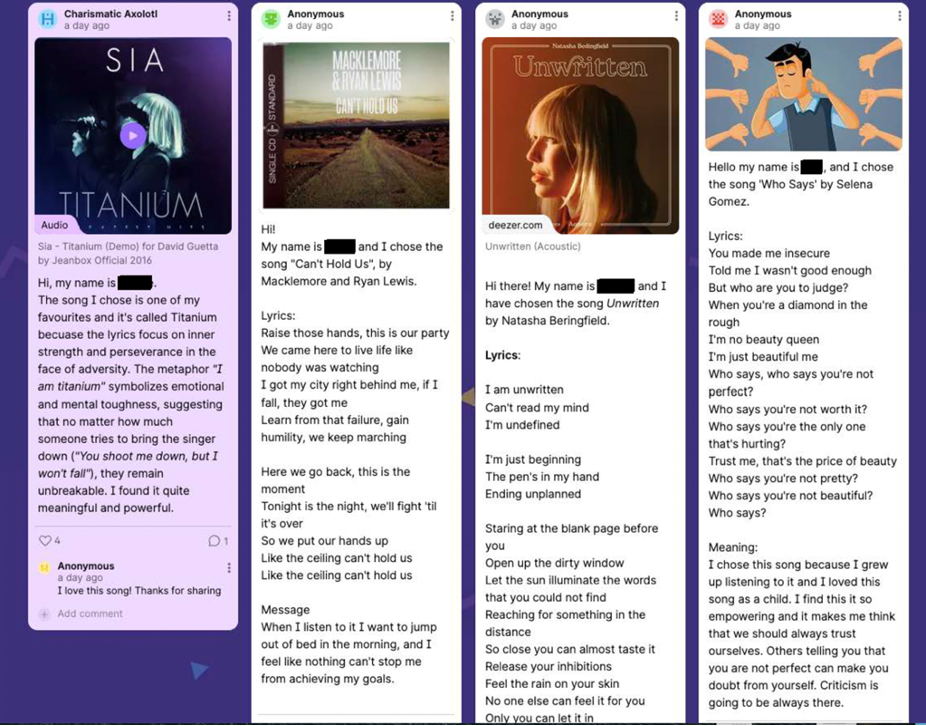

The discussion featured took place on Padlet. Table 2 includes information about the twenty-five students and their chosen songs in the activity. Students in both the U.S. and Spanish class groups chose a mix of English and Spanish songs. Also, an international student in the U.S. group from Brazil shared a song in her native Portuguese. The activity encouraged students to think deeply about themes of empowerment in music. It served as an icebreaker activity between the groups, with peer responses echoing their reactions to each other’s posts about chosen songs. For example, a student from the U.S. class who replied to a Spanish student’s post about the song Unwritten said, “I loved the message of your song. It is so empowering, yet at the same time, it carries the fear and responsibility of being the owner of our own story and path. However, I believe that is the beauty of life—to be empowered to make our own decisions and embrace the changes we need.”

Table 2. Student Groups and Their Song Choices

| University | Program | Song Choices |

| U.S. Group | MA TESOL |

|

| TEFL Certificate |

|

|

| Spanish Group | Official Master’s Degree in Teacher Training for Secondary Education, Vocational Training, and Language Teaching (English Language Specialty) |

|

The following section shares examples of student discussion posts (Figures 4 and 5). Posts included links to music videos online as well as chosen images to represent the songs. Some students directly linked to official music videos or audios and used the automatic preview images in posts. These examples are representative of posts students shared with images, lyrics excerpts, and explanations (sometimes accompanied by hyperlinks to music videos). The initial posts and peer responses reflect selection of songs that highlight resilience, whether that be in relationships with others or with themselves. Peer comments showed recognition of some familiar songs that are shared favorites and appreciation of new songs learned.

Examples of student work

A post about Maria, Maria (Figure 5) prompted a discussion about the play which originally featured the song and showcased the strength and perseverance of Brazilian women. A discussion within the post about Canción sin Miedo, also prompted a reflective response about Mexico’s feminist movement. Most posts celebrated women’s strength and resilience, but one post about the song Stronger brought up another relevant side to the discussion: “Although, the message of women empowerment is important…the expectation for women to always be fighters can be exhausting.”

Student feedback

Participant feedback included an overwhelmingly positive response to the activity. A theme from the feedback data was that they enjoyed the discussion as a way to meaningfully reflect on pedagogical concepts like multimodality, motivation, and engagement:

- “The multimodal reader-viewer discussion activity was an engaging and insightful experience. It allowed me to understand better how multimodality works in a classroom activity… I also appreciated how, despite having the same topic, different perspectives emerged from the song lyrics making the discussion enriching.”

- “I think it was a very interesting and interactive activity in which we had the opportunity to talk about a theme that we all like (music) and share our songs, this is very motivating for students in general.”

- “I find the experience highly interesting since we can learn and consider many songs that are empowering. Learning English through songs is always going to be engaging and meaningful for students.”

An additional theme was that students found the activity an interesting, creative, and engaging way to initially connect with their international partners:

- “I think it is a really fun way to get in touch for the first time with the [U.S.] students! It is really interesting to get to know their music taste at the same time that we get to know each other.”

- “I really liked this activity because we get to know more about our classmates based on our musical taste. This way we can connect.”

- “I love talking about music and the way it makes me feel so I think is a really interesting activity to start talking and meeting (even if it’s online) new people!”

The discussion and anonymous feedback on the activity indicated that groups from both universities found the activity fruitful and engaging as part of their teacher training classes. The only suggestion for improvement in student feedback was the desire for peers to more clearly label their home universities in their posts to clarify the groups as they responded to each other.

Activity takeaways

This activity inspired by Multiliteracies and LbD explanations in Fernandes (2023) and Zapata (2022) is an example supporting the value of creative multimodal activities as part of English language teacher training. It was an opportunity to focus on the emotions of a song through plurilingual perspectives and share reflections on empowerment across two collaborating international classrooms. Providing teachers in training an opportunity to engage in this type of activity may also encourage them to use a similar multimodal activity with their classes. As with online discussions in general, a recommendation for teachers using this type of activity is to provide students with ample time to craft their first posts and a second deadline for peer reply to posts to encourage discussion. The steps taken in this activity are shared in the hopes that others will adapt and modify the activity for their own contexts.

Acknowledgements:

This activity was created as part of a larger Fulbright postdoctoral/early career research grant project titled A Multiliteracies Approach for Telecollaborative Language Teacher Training and Service-Learning hosted at the University of Huelva within the Research Center “Contemporary Thinking and Innovation for Social Development” Grupo de Investigación ReALL (Research in Affective Language Learning) and the PIONEER European University Alliance R+D+i Project “Multiliteracies for adult at-risk learners of additional languages (REF.PID2020- 113460RB-100). Gratitude is extended to the participating faculty group at the University of Huelva (UHU), especially Dr. M. Carmen Fonseca-Mora, Dr. Beatriz Peña-Acuña, and Dr. Analí Fernandez-Corbacho, for their collaboration in this grant project.

References

Fernandes, A. C. (2023). Multiliteracies in EFL teacher education: A repertoire of practices. The International Journal of Literacies, 30(2), 189-208. https://doi.org/10.18848/2327-0136/CGP/v30i02/189-208

Fonseca-Mora, M. C., & Camacho-Diaz, M. D. (2022). La Imagen de la mujer en el flamenco. Editorial Universidad de Huelva.

Kalantzis, M., & Cope, B. (2023) Multiliteracies: Life of an idea. The International Journal of Literacies, 30(2), 17-89. https://doi.org/10.18848/2327-0136/CGP/v30i02/17-89

Kalantzis, M., & Cope, B. (2025). Learning by Design: Pedagogy. New learning online. https://newlearningonline.com/learning-by-design/pedagogy

Kalantzis, M., Cope, B., & Learning by Design Project Group (2005). Learning by Design. Victorian Schools Innovation Commission: Common Ground Publishing

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). Sage.

New London Group: Cazden, C., Cope, B., Fairclough, N., Gee, J., Kalantzis, M., Kress, G., Luke, A., Luke, C., Michaels, S., & Nakata, M. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-93. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.66.1.17370n67v22j160u

Zapata, G. C. (2022). Learning by design and second language teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Routledge.