In order to find potential tools, scaffolds, and differentiation to be employed by English Language (EL) and content teachers alike, a small qualitative study was conducted that found that English learners (ELs) displayed better reading comprehension and increased memory retention of the chapter events when reading the graphic novel versions of a text in comparison to the traditional book format.

Key words: language learners, ELL, graphic novels, comics, reading, reading comprehension, memory recall

Using Graphic Novels to Increase Comprehension and Recall

As an English Language teacher, I work with English learners (ELs) not only by helping them with listening, speaking, reading, and writing, but also by providing tools and scaffolds to help them successfully navigate the English language in their mainstream classes. Sadly, ELs can face more challenges in the classroom than their native speaking peers, including, but not limited to, skill transfer from the learner’s first language L1 to the target language (L2); the unique nature of student’s L1 (e.g. is there a different alphabet? Is the language a spoken language only?); interrupted schooling; and the possibility that school is the only place these learners are hearing and using their L2 (Ford, 2005). My personal belief in the power of visuals in the form of comic books and graphic novels led me to study graphic novels as a potential tool for EL reading success in elementary education.

The purpose of my study was to explore how the use of graphic novels in an EL classroom could increase reading comprehension and memory recall. I sought to find answers to the following questions:

- How can graphic novels affect the proficiency of reading comprehension, as shown by increased performance on the task of retelling, for middle school ELs in comparison with a text only novel?

- In what ways can the memory recall of a chapter’s events be affected by the use of a graphic novel adaptation in contrast with the traditional text format?

The purpose of this article is to provide a brief summary of the major findings that emerged from my research. The article will begin by discussing the usefulness of visual aids for reading comprehension and memory recall. Next, it will introduce graphic novels, and their potential for serving as visual aids in the classroom. Finally, my study and findings, followed by their implications, will be discussed.

Terms

There is a lot of confusion regarding the true difference between the terms comic and graphic novel. Will Eisner originally defined comics as simply “sequential art” (1985). Scott McCloud later defined them as a “collection of pictures and words arranged side-by-side in a sequential story format” (McCloud, 1993). The term graphic novel maintains this sequential art aspect, but differs in that instead of being serialized, they are often published as original trade paperbacks that tell a single story from beginning to end, more similar to a traditional novel (Arnold, 2003). A casual search will show there are graphic novels for just about every subject or literary genre with equally thought-provoking themes as those present in traditional novels, but with the added scaffold of visuals. It is this visual scaffold aspect that allows both graphic novels and comics the potential to provide support for struggling readers while still working through the same difficult themes and complicated stories that exist in the text-only format. It is when we look through the lens of the visual scaffold that is provided by both comic books and graphic novels in education that the difference between them becomes negligible. To avoid confusion in this article, the term “graphic novel” will be used as a catchall to describe both comic books and graphic novels, as it is their shared visual scaffolding aspect I am focusing on, and not whether they are serialized (comics) or whole works (graphic novels). The graphic novel used in this study was published as a whole work in sequential story format.

Visual Aids and Reading Comprehension

Visuals have long been hailed as useful aids in assisting students in their reading comprehension (e.g., Levie & Lentz, 1982; Levin, Anglin, & Carney, 1987). Luckily for EL educators, visuals are ever-present within the context of graphic novels, which may aid reading comprehension. Any student confusion that could arise regarding the comprehension of the plot, characters, or setting may have a more concrete representation in the accompanying visual than appears in the graphic novel format of the story. A graphic novel’s ability to display the relationship between words and visual images simultaneously allows readers an easier path to imagine what they just read, a fundamental key to facilitating comprehension (Eisner, 1998). In fact, this path seems to naturally assist students with the use of a key reading strategy, visualization, or forming mental pictures in students’ minds, which helps students to “…find they are living the story as they read” and therefore increase their enjoyment and understanding (Roe & Smith, 2005, p. 333).

Additional research suggests that pictures presented alongside text facilitates comprehension by reducing the cognitive load of dense text or more sophisticated concepts (Burke, 2012; Mayer 1994, 2014; Metros & Woolsey 2006; Schnotz, 2002). A recent study of native English-speaking university students, for example, found that incorporating visuals into a lesson on how blood circulates through the heart resulted in a better understanding than text alone (Butcher, 2006). In addition, the usefulness of visuals has been found effective for adult ESL learners (Liu, 2004). The results of Liu’s study showed that low-level adult EL students given a high-level text with added visuals scored significantly higher on a series of comprehension recall protocols immediately administered than those given the high-level text only.

Paivio’s (1991) dual coding theory, which discusses the process our brain undergoes during reading, sheds light on how graphic novels may facilitate reading comprehension. Paivio argues that all learners learn to read or write using two separate language systems of cognition. The first is the verbal system, which is the information garnered from words, sequence, speech, and writing. The second system is the imagery system, consisting of non-verbal information, such as images and visualizations. Paivio (1991) explains that students are making connections between these two different systems simultaneously while they read, and it is these connections between the two different systems that allow for better understanding and recall. Essentially, information is stored both verbally and non-verbally, as words and images, and in this format one can recall information to a greater degree. Graphic novels, it seems, have a unique format that includes both of the language systems of cognition in one reading experience; they are student reading materials with visual scaffolds already designed into them.

Visual Aids and Reading Recall

Paivio (1991) further argues that the visual portion of the system of the dual coding is even more important when it comes to memory recall. An early study that seems to support the connection between visuals and memory recall was conducted by Omaggio (1979), which measured comprehension among Native English speakers reading several different texts with and without visuals in both the L1 of English and the L2 of French. He found that while the visuals had no effect on reading comprehension in the English L1, they did have a positive effect on reading comprehension and recall in the French L2 reading (Omaggio, 1979).

In another study, two different groups of participants were given readings, with one group using a text only excerpt, and a second group using a text with added visuals (Waddill & McDaniel, 1992). Upon completion of the reading of the excerpts, participants were simply asked to write a much as they could recall on the subject. It was found that those from the group with the added visual support were able to recall a greater amount of information than those without (Waddill & McDaniel, 1992).

It is worth noting that visuals are not a panacea for comprehension; a study conducted by Daniel Bruski (2011) found that a group of beginning-level adult language learners, some first language non-literate and some first language literate, produced non-universal understandings and inaccurate descriptions of what was occurring in the visual when presented with images of speech bubbles, arrows, and symbolic signs. Context and cultural background were shown to play a major role in differing interpretations of images, noting that misinterpretations of meaning that may occur with visuals in the same manner it may with text.

Graphic Novels: A Visual Scaffold

Visuals can sometimes better illustrate a concept. This is the reason that manuals contain images alongside written instruction, and why companies use logos to brand themselves: visuals are not affected as easily by language barriers (McCloud, 1993). Visuals are more concrete. So, when applying this to a classroom, the simplified visual nature of comic books may provide a scaffold by allowing the reader to focus their attention on important text aspects as well as eliminate potentially confusing aspects.

The Study

This qualitative classroom study used retells and memory recall assessments to determine how graphic novels versus traditional novels might support comprehension and memory of texts.

Setting and participants

The school setting of this qualitative action research study was a grade five through eight environmental, science, technology, engineering and math (E-STEM) public middle school. The fifth grade class in which this research was conducted consisted of seven students, five boys and two girls, all of whom participated in the study. All participants had been in the United States for a minimum of two years, were labeled as Limited English Proficient (LEP), and had received regular prior formal schooling. Their language levels ranged from 2.8-3.9 according to the World Class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA) scale used for assessing English Language levels in Minnesotan K-12 schools, indicating they were low-intermediate students, and received sheltered English instruction from an English as a Second Language (ESL) instructor, also the author of this study. The sheltered classes provide language support while simultaneously meeting mainstream content standards.

Data collection

Instruments

I used student-produced written retells to show comprehension of the text, and multiple choice questions to measure recall.

The process of retelling requires students to consider the information they read, and summarize what they understand; it also includes higher order thinking skills including the processing of schema, the ability to process and filter textual information, the ability to sequence events, the ability to determine the relative importance of events, the ability to later recall this important information, the ability to organize this information in an understandable and meaningful way, and the ability to draw conclusions about the relationships that may exist within ideas in the text itself (Fisher & Frey, 2011; Klingner, 2004; Shaw, 2005). With the variety of required skills needed to produce a retell, it has been argued that retells are a powerful way to measure reading comprehension or to check for understanding (Shaw, 2005).

Retell preparation

To begin the process, I modeled how to complete the graphic organizers to help the students capture the essential information needed for a retell.

After modeling, the graphic organizers were practiced with a traditional novel. A chapter of the young adult, science-fiction novel City of Ember was read aloud to the whole group at the end of each class period for the first eight chapters. This text was chosen not only because the lexile levels for both the traditional and graphic novel fell within the reading level range of the participants, but also because the graphic novel uses a great deal of the same text and quotations from the traditional novel. Using these beginning chapters as practice for the graphic organizers and the written retells, gradual release was used through first modeling the act of completing the organizer, and then slowly shifting this responsibility onto the participants (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983).

After this practice with the traditional novel, the graphic organizers were practiced with a graphic novel of the same City of Ember text. This was also done at the end of each period for three consecutive days. The same graphic organizers were used to help participants complete written retells for each of these graphic novel chapters daily. This gradual release assured participants could complete the organizers and retells independently for the study.

Data collection

Upon reaching Chapter 11, participant retells began to be used for data collection in the study. Participants began the process of using the end of the class period to independently read, fill out their graphic organizers, and compose their written retells from these organizers. They created a new retell for each chapter read on each consecutive day. The use of the traditional novel and the graphic novel alternated for the purpose of comparison. Only the data collected from the independently-produced student written retells for Chapters 11-18 were formally scored, and their results were used as data in this study.

In addition to completing written retells of chapter events, participants were given a short three to four multiple-choice question quiz after a 24-hour period to gauge recall from the previous day’s chapter. The assessment contained information specific to the last chapter read, and each assessment was similar in format, regardless of the text medium (traditional or graphic novel) that it was used to assess.

Retells were collected during the final 15 minutes of each class period for approximately six school weeks.

Data analysis

The retell data was analyzed using participants’ final written retells. These retells were assessed using a six-category instructor-created retell-scoring rubric (Table 1) focused solely on student delivery of information related to their comprehension of the story holistically. The rubric emphasized construction of meaning rather than anything sentential or sub-sentential such as construction of clauses, spelling, or punctuation, thereby eliminating possible loss of points due to language transfer errors. The rubric categories were used to assess retell of the chapter’s key events, sequence of events, problem, resolution, characters and setting. Scores ranged from zero to three for each category, resulting in 18 points total. Scores resulting from a traditional chapter and from a graphic novel chapter were compared.

Table 1. Recall Rubric

| Idea Unit | Verbal Prompts Used | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Key idea of chapter’s event | What important events took place during this chapter? | Wholly inaccurate or not included | Does not recall many key ideas or inaccurately expresses events | Accurately expresses some key, although incomplete, events. | Accurately expresses all key events in the chapter to completeness. |

| Sequence of events | How does this chapter begin? What was the order of the events? | Wholly inaccurate or not included | States some events in order, but with some inaccuracies. | States many events in order, but with some inaccuracies | Accurately states events in correct order. |

| Problem | What was one important problem in this chapter? | Wholly inaccurate or not included | Includes chapter non-specific, vague, or unrelated problem. | Chapter’s problem description is accurate but vague or with some inaccuracies. | Accurately states chapter’s problem. |

| Resolution | How does the chapter end? Is a problem solved? | Wholly inaccurate or not included | States chapter non-specific or unrelated resolution. | Chapter’s resolution description is accurate but vague or with some inaccuracies. | Accurately states chapter’s resolution. |

| Characters | Who were the important or main characters in this chapter? | Wholly inaccurate or not included | States chapter non-specific or unrelated character descriptions or includes unimportant characters. | Chapter’s character description is accurate but vague or with some inaccuracies. | Accurately states chapter’s main characters. |

| Setting | Where and when does this chapter take place? | Wholly inaccurate or not included | States chapter non-specific or unrelated chapter setting. | Chapter’s setting is accurate but vague or with some inaccuracies. | Accurately states chapter’s setting. |

The data from the multiple choice memory recall assessments was assessed using the standard percentage basis. For example, three of four correct was assessed at 75%. The scores were totaled and given a percentage point for ease of scoring, as well as averaged to create a student personal average on the four traditional novel chapters as well as student personal average on the graphic novel chapters.

Findings

The results of this study found that when students read the graphic novel chapter, they displayed increased scores in both reading comprehension and in memory recall assessments.

Reading comprehension

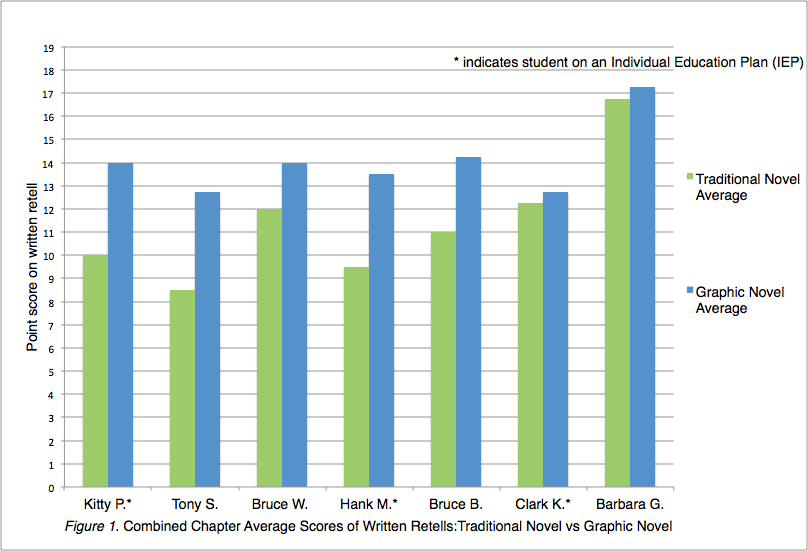

When the total rubric score of the four written retells for the traditional novel were averaged, and compared to the average of the total scores of the four written retells for the graphic novel, all seven student participants’ averages increased with the use of the graphic novel version in place of the traditional novel. The averaged increase in score when using the graphic novel was an increase of 2.64 points of the rubric’s 18 total points. The maximum increase in average score was 4.25 and minimum increase in average score was an increase of .5. Figure 1 displays shows this comparison.

Memory recall

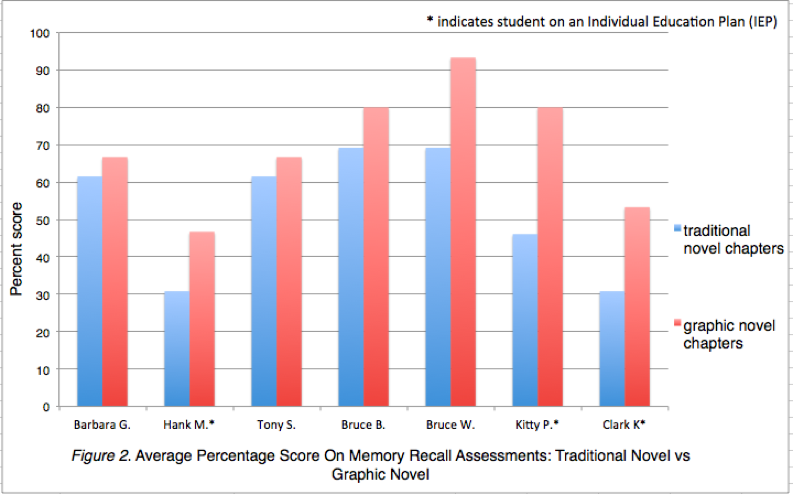

The average percentage score on memory recall assessments increased when students had read graphic novel chapters with seven of the seven participants, with an average higher score of 16.8% on the chapters read in the graphic novel format. Figure 2 shows this comparison.

The largest percentage score increase for a student participant was a 33.9% increase from 46.1% on the traditional novel memory recall assessment, to 80% on the graphic novel memory recall assessment.

Discussion

Research on visuals (Butcher, 2006; Omaggio, 1979; Waddill & McDaniel, 1992) as well as this study suggest the importance of visuals for language learners as they progress towards the language levels of their native speaking peers. ELs in this study likewise seemed to be able to better reproduce the main plot elements of a story while retaining comprehension after reading graphic novels. Furthermore, this study suggests ELs will even remember the previous day’s reading better when using the graphic novel format, allowing them to better maintain their understanding as they progress throughout the story. These results seem to produce similar findings to those attained by Lui, Butcher, Waddill and McDaniel, and Omaggio: participants consistently show increased comprehension and can recall texts more accurately when they are provided scaffolding in the form of visuals.

While these findings apply only to the limited number of participants in this study, their promise warrants additional research of the topic on a larger scale and with ELs of other age groups and language levels. Additionally, one could explore the possible benefits of graphic novels with other student populations who benefit from reading scaffolding, including those with Individual Education Plans (IEPs) and learning disabilities.

Activities with Visual Literacy

All classroom teachers could begin integrating the use of comic books and graphic novels into the classroom by identifying the goal for the lesson, and determining if graphic novels could be used as alternate or companion readers. If the goal is to have students identify character development, for example, or to identify the conflict and other plot elements of a story, it may be of no consequence whether students do so by reading the traditional versus the graphic version of the novel.

Another implementation for graphic novels is simply to use them in the same manner as leveled readers by creating reading groups based upon needs. An EL classroom can contain very diverse needs when it comes to text studies, which at one point had me splitting our class into three different groups including one group reading a Pearson ESL Leveled Frankenstein reader, a small group reading a graphic novel adaptation of Frankenstein, and a final small group reading the traditional novel. The group reading the graphic novel adaptation was actually reading a more difficult text than the leveled reader group, but they had the built-in scaffolds of pictures to give them the visual support they still needed to access the higher level text. All of the groups were then able to come back together and participate in the same discussions, activities, and check-ins despite the vast differences in their reading abilities.

Graphic novels could be used as an initial at-level replacement for the traditional novel version for below-level reading groups, they could be pre-taught or used for front-loading before attempting a traditional text that may be above a reader’s level with visual scaffolds removed, or they could be used as a supplement to the traditional novel.

The graphic format can be used for student-produced work as well, as it is a perfect format for presenting concepts like sequencing, dialogue, predicting, and summarizing. If students are struggling to write a good summary, educators could allow students to create a visual summary of the events of a chapter using blank comic panels that students fill in. Students will still be required to show they understand the sequence of events through the use of sequential panels, and can show whether they grasped the setting and important chapter events through their visual summary. If teachers want to incorporate writing into the summary, they may require students to produce dialogue by requiring a set amount of speech balloons, or scaffold their writing by adding cloze passages and sentence starters in the panels for students to complete.

Conclusion

ELs are often required to perform difficult tasks that require native-like levels of comprehension. Content teachers need a varied set of tools and strategies to help ELs develop their language levels and experience greater success. This initial, albeit limited, study suggests that the use of graphic novels as one of these tools can help language learners improve achievement in reading comprehension and memory retention. As ELs use these tools to reach the level of reading comprehension of their native speaking peers, they may be more willing and confident to retell, participate in class readings, and take risks in their learning. While the use of visuals has always been a hallmark of good language teaching, this study shines a light on the potential of the often-overlooked format of graphic novels for increasing reading comprehension and memory retention among ELs.

Links to Resources

If you are interested in learning more about the medium of graphic novels, I highly recommend Scott McCloud’s work on the topic, “Understanding Comics.” The text delves into the graphic novel as an art form, and serves to really remove the stigma that comic books are just for children. http://scottmccloud.com/

The links below can provide with you additional information regarding using graphic novels in your classroom, including additional resources and lessons for teachers, comic book and graphic novel listings, and more.

The American Library Association’s yearly graphic novel reading list: http://www.ala.org/alsc/publications-resources/book-lists/graphicnovels2018

Reading with pictures includes research, content, and best practices for integrating comics into curriculum: http://www.readingwithpictures.org/

Getgraphic.org gives up-to-date news in the graphic novel world as well as ideas for how to use graphic novels as a tool for literacy: https://www.buffalolib.org/content/get-graphic

The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund has library and educator tools for using graphic novels: http://cbldf.org/using-graphic-novels/

Readingrockets has classroom ideas and booklists for graphic novels in the classroom: http://www.readingrockets.org/article/graphic-novels-kids-classroom-ideas-booklists-and-more

References

Arnold, A.D. (2003). The graphic novel silver anniversary. Time Online Edition. Retrieved from http://content.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,547796,00.html

Bruski, D. (2012). Graphic device interpretation by low-literate adult ELLs: Do they get the picture? MinneTESOL/WITESOL Journal, 29, 7-29.

Burke, B.P. (2012). Using comic books and graphic novels to improve and facilitate community college students’ literacy development. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. (UMI No. 3546922)

Butcher, K.R. (2006). Learning from text with diagrams: Promoting mental model development and inference generation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 182-197.

Eisner, W. (1985). Comics and sequential art. Paramus, NJ: Poorhouse Press.

Ford, K. (2005, July). Fostering literacy development in English Language Learners. Color in Colorado. Article retrieved from http://www.colorincolorado.org/article/fostering-literacy-development-english-language-learners

Frey, N., & Fisher, D. (2004). Using graphic novels, anime, and the internet in an urban high school. English Journal, 93,19-25.

Frey, N., & Fisher, D. (2011). The formative Assessment Action Plan. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Klingner, J.K. (2004). Assessing reading comprehension. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 29(4), 59–70.

Levie, W.H., & Lentz, R. (1982). Effects of text illustrations: A review of research. Educational Communication and Technology, 30(4), 195-233.

Levin, J.R., Anglin, G.J., & Carney, R.N. (1987). On empirically validating functions of pictures in prose. In D.M. Willows, & H.A. Houghton (Eds.), The psychology of illustration, volume 1. New York: Springer-Verlag. (pp. 51-85).

Liu, J. (2004). Effects of comic strips on L2 learners’ reading comprehension. TESOL Quarterly, 38(2), 225-243.

Mayer, R.E. (1994). Visual aids to knowledge construction: Building mental representations from pictures and words. Advances in Psychology, 108, 125-138.

Mayer, R. (Ed.). (2014). The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding comics: The invisible art. New York: Paradox Press.

Metros, S.E., & Woolsey, K. (2006). Visual literacy: An institutional imperative. EDUCAUSE Review, 41(3), 80-81.

Omaggio, A.C. (1979). Pictures and second language comprehension: Do they help? Foreign Language Annals, 12, 107–116.

Paivio, A. (1991). Dual coding theory: Retrospect and current status. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 45(3), 255-287.

Pearson, P.D., & Gallagher, M.C. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, 317-344.

Roe, B.D., Smith, S.H., & Burns, P.C. (2005). Teaching reading in today’s elementary schools (9th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Schnotz, W. (2002). Towards an integrated view of learning from text and visual displays. Educational Psychology Review, 14, 101-120.

Shaw, D. (2005). Retelling strategies to improve comprehension: Effective hands-on strategies for fiction and nonfiction that help students remember and understand what they read. New York: Scholastic.

Snowball, C. (2005) Teenage reluctant readers and graphic novels. Young Adult Library Services, 3(4), 43-45.

Waddill, P.J., & McDaniel, M.A. (1992). Pictorial enhancement of text memory: Limitations imposed by picture type and comprehension skill. Memory & Cognition 20, 472-482.