In this article, we explore how a strengths-based coaching model embedded in a TESOL-certification program for in-service content area teachers can shift teachers’ practice and mindset when working with multilingual learners (MLs) in high school classrooms. The study focused on the impact of the coaching model on teachers and in turn their ML students.

Key words: teacher education, practicum coaching, shifts in teacher practice, coaching dispositions, high school, literacy

Introduction

The number of multilingual learners (MLs) in New York City (and across the United States) continues to grow. In 2019, there were more than 150,000 MLs in New York City schools, with MLs making up more than 15% of the student population; and more than a quarter of those ML students (42,860) were in high school grades (New York City Department of Education, 2019). In 2022, the 8th grade National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) for Reading Achievement results showed that just 5% of ML students were designated at or above grade level proficiency in reading in English (The Nation’s Report Card, 2022). The situation in New York City is more dire still, where the 2022 8th grade NAEP data showed that less than 1% of MLs were proficient in reading in English (The Nation’s Report Card, 2022).

Our project is a New York City-based program co-developed by a higher education institution and local non-profit that provides comprehensive services to New York City schools, and funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of English Language Acquisition through the National Professional Development grant office. The program aimed to increase the supply of effective teachers certified in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) who understand how to support students’ content-area literacy – defined as the use of language and literacy to comprehend, analyze, and generate content – while attending to students’ cultural and linguistic differences.

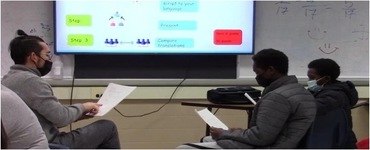

Our theory of change posits that if content-area teachers participate in a program that combines graduate coursework, experiential professional development (PD), professional learning communities and coaching focused on evidence-based instructional strategies and cultural relevance to learning, teachers will shift their practices to meet the needs of English learners (ELs) in the classroom. By implementing recommended practices and gaining greater confidence in their skills, teachers will support students’ development of language and literacy, as measured by the state TESOL exam, and their content learning, as measured by their progress to graduation (i.e., state content exams and credit accumulation). With teachers approaching this training with colleagues from their schools, teachers will contribute to improvement in the school’s service for ELs; see Figure 1.

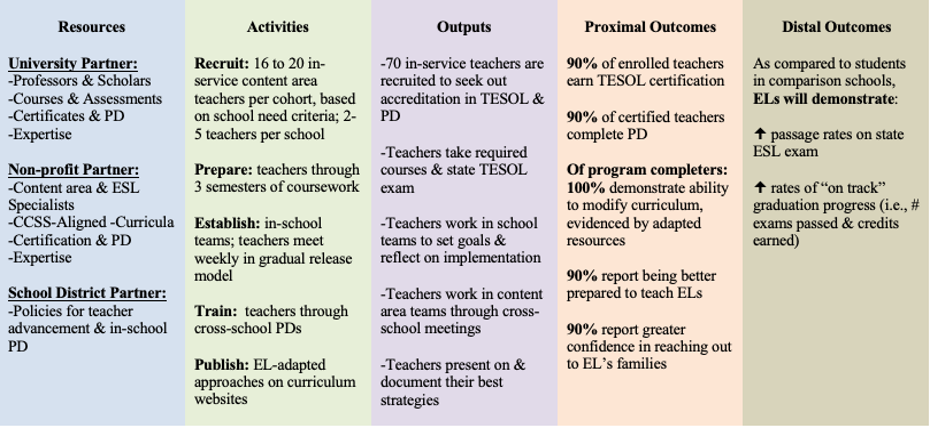

The program recruited teams of teachers to participate in a cohort-model. The design included four graduate courses, cross-school (cohort-based) PD, in-school coaching and teaming, and a TESOL practicum; see Figure 2.

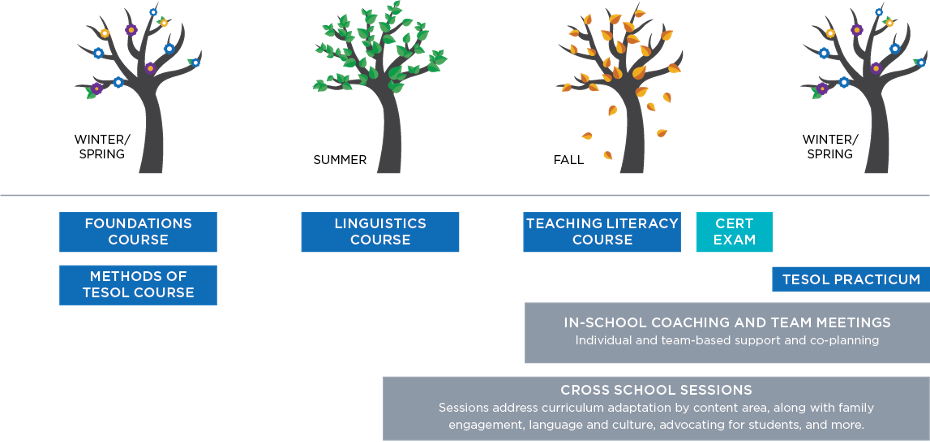

A cognitive strategies approach to literacy instruction was the central pedagogical intervention promoted by the program (Frey & Fisher, 2011; Kim et al., 2011; Matuchniak et al., 2013). Explicit instruction of cognitive strategies, including modeling and meta-reflection, builds students’ awareness how to direct their attention before, during, and after reading in order to derive deeper meaning from the text; see Figure 3.

(adapted from Olsen & Land, 2007, p. 276–278)

Unlike traditional TESOL-certification programs, the practicum course, provided by the university, allowed teachers to receive job-embedded coaching. Teachers were observed and coached by local non-profit staff with significant teaching and coaching experience, eight times on average during the course of a school year, and were expected to prepare and share lesson plans in advance of observations, spend an hour debriefing each observation (coaching), and reflect post-observation through a written journal response. Successful completion of the practicum earned teachers one college credit, however, engaging in practicum activities is where teachers in the program spent the most time. The focus of this analysis is on investigating the impact of the program’s coaching model on participating teachers and their ML students.

Methodology

Participants

In total, 82 teachers from 20 schools enrolled in the program. The 20 schools included in the program were located over four boroughs of New York City (n=5 Brooklyn; n=8 Bronx; n= 4 Queens; n=3 Manhattan) with a range of 1 to 13 teachers per school participating. Over the course of five years, 72 teachers successfully completed the program with 45 teachers receiving TESOL state certification. Fifty-two program completers from four cohorts volunteered to participate in the research study.

Data collection: Surveys

Teachers participated in three surveys: a pre-survey at the start of the program, a post-survey at the end of their 18-month cohort, and a retrospective survey at the end of the 5-year project. Surveys gathered data on the value of teacher training, coaching support, and within-school teaming, as well as the instructional cognitive strategies. Additionally, surveys measured teachers’ confidence in meeting the needs of MLs, understanding the balance of language and content literacy, and leveraging students’ home language and culture.

Data collection: Focus groups and interviews

Each cohort of teachers participated in an hour-long focus group discussion at the end of their 18-month program. Discussion questions focused on programmatic activities (professional development, coaching, team meetings, and coursework), teachers’ use of cognitive strategies in their classrooms, and how the program changed teacher practice and students’ understanding of language and literacy. At the end of the 5-year project, six teachers participated in hour-long retrospective interviews. Interview questions focused on teacher reflections on changes in their teaching practice, support provided by the program, and the longer-term impact of the program’s coaching model a year or more after their participation.

Data analysis

Data were coded using a combination of coding systems developed iteratively from theory and a reading of the data (Chi, 1997; Huberman & Miles, 2002). The data was then synthesized to identify patterns or themes.

Data collection and analysis: Student achievement data

Student-level performance data of the program’s teachers’ students were compared to data from students taught by other teachers in matched schools within the New York City Public Schools. ML students in New York State participate in an annual achievement test (NYSESLAT), measuring four English language proficiency areas (listening, speaking, reading, and writing). The four proficiency areas are totaled to create a scaled score used to place students by needs of service within the school. Participating and non-participating students’ 2019 NYSESLAT scores were compared using a General Linear Model, controlling for disability status, economically disadvantaged status, and prior year NYSESLAT scale score.

Findings

We found there to be significant shifts in teachers’ beliefs around their role in meeting the needs of multilingual learners. Additionally, teachers made shifts in their teaching practice to incorporate explicit instruction of metacognitive and cognitive strategies that accelerate learner independence and have proven effectiveness for MLs’ improved reading and writing skills.

Teacher belief changes

Eighty percent of surveyed teachers (n=35) reported that their thinking changed in terms of their role in facilitating learner independence after program participation (on a confidence rating scale of less than, about the same, or more than before the program). Throughout the program, teachers were encouraged to think deeply about the kinds of teaching moves that would allow for students to become independent learners. Figure 4 offers a look at a foundation resource used with teachers in the program. This resource was meant to provide a window into the kinds of student behaviors that distinguish more independent learners from dependent ones (Hammond, 2015).

Seventy-one percent of surveyed teachers (25 of 35) said their thinking has changed on addressing the academic achievement of MLs. In the following quote, a teacher is describing a new approach in grouping students that would allow for multilingual learners to learn from their monolingual peers, and vice versa.

“I think my shift was to think of all students, all people really as language learners. All of my students are lacking some vocabulary. So from that perspective, they are all still learning English. The shift for my ML students is that we may differentiate for them, you know, translate something for them or change it up somehow, but they are mostly sitting and working with other students, [where] at least one or two other students are not classified as an ML.”

Shifts in teaching practice

Eighty percent of surveyed teachers (28 of 35) retrospectively reported that in the years since participating in the program, they continued to provide explicit instruction of both cognitive strategies and disciplinary content, and that they support students in being metacognitive at least several times a month. A substantial subset of teachers support students in being metacognitive weekly and daily as a result of participating in the program.

“I think a big shift that I also experienced was building students’ meta awareness of why we’re doing certain things in class that’s become a new part of my lesson plan. Everyday is just talking with students about why we’re doing what we’re doing in class that day and in planning I feel having that feature has sometimes made me realize that I need to revise my objective or choose a different focus because it’s not as useful as I thought it would be when I try to justify it so I feel that’s been a really important shift, is just building that meta awareness and as a result having a curriculum that is as useful as it can be there’s no fluff I don’t think.”

Increased student outcomes

ML students in program (n=132) had a significantly higher NYSESLAT test scale score than ML students in the non-program classrooms (n=106), F(1,233)=11.12, p=.001, ηp2=.046. In addition, we also examined the difference between program students’ and non-program students’ change in NYSESLAT proficiency levels (Entering, Emerging, Transitioning, Expanding, and Commanding), from spring 2018 to spring 2019. Results indicated that ML students in program had a significantly larger increase in proficiency level than non-program students, F(1,233)=9.21, p=.003, ηp2=.038.

Discussion: Guiding principles behind the coaching model

Our study highlights that the quality of coaching impacts the moves and shifts teachers make around their teaching practice. Seventy-four percent of surveyed teachers (28 of 38) said coaching was impactful on their teaching practice. We dug further into which elements of the coaching model were particularly effective. Seventy-two percent of surveyed teachers (26 of 36) reported that coaching “that helped me identify how I can improve my instruction was highly impactful.”

Building on the coaching frameworks of Knight (2017, 2019) and Lindsey et al. (2019), our project’s coaching model was structured with four “coaching dispositions” described below:

Building trusting relationships

In the year leading up to the practicum course, the coach spent time building relationships with each individual teacher in the program. The relationship started early in the 18-month program through the coach teaching multiple graduate-level courses and engaging with teachers at professional development sessions. During this time, the coach stated, “People learn better when someone shows a genuine interest in getting to know them on a personal level.” During the practicum, the coach engaged with students in the teacher’s classes and in the hallways building trusting relationships

“I can’t remember the exact circumstance, but there was one specifically where I was so overwhelmed and it was a bad day. [The coach] came in and I remember crying and I was embarrassed. She said, ‘You don’t need to be embarrassed. This happens. Let’s take a look at the lesson and see what happened.’ And she went through the lesson with me and she gave a lot of amazing feedback. She was just very nurturing and very understanding, but also because she fostered that relationship, I felt accountable to her. So when she came in, I never wanted to not be ready for her. This was very important to me and I really respected her.”

A central belief guiding the coaching is that each partner brings something different and important to the partnership. The teacher brings deep insider knowledge of the discipline, knowledge of the students, and knowledge of the school context. What the coach brings is pedagogical expertise focused on culturally responsive teaching and learning for multilingual learners, explicit instruction, metacognition, and cognitive strategies.

Adopting an asset-based mindset

The coach approached each interaction with three lenses:

- To build teacher confidence by focusing on what was positive and approaching improvements with a strengths-based perspective.

- To personalize each session to focus on the current needs of the teacher while keeping in mind the goals of the project, school, and teacher.

- To make sessions learner-focused.

An organizing principle of the practicum is that everyone is doing the best they can with the resources they have available to them at the moment. The coaching conversation was meant to bring more resources to the teacher.

“There were always positives in every meeting we had. It wasn’t just like negative, negative, negative. So many more positives than negatives, just so encouraging, especially when this was really the first time that I was doing something like that…[even] the criticism didn’t come off as criticism, they come off as positive things. All the coaching sessions were just so helpful and warm and fuzzy, which I know is a strange thing to say about coaching sessions.”

“The coaching session would be about my students, and my lesson, and specifically the situation that we were in, so it was relevant. I would receive a lot of useful feedback.”

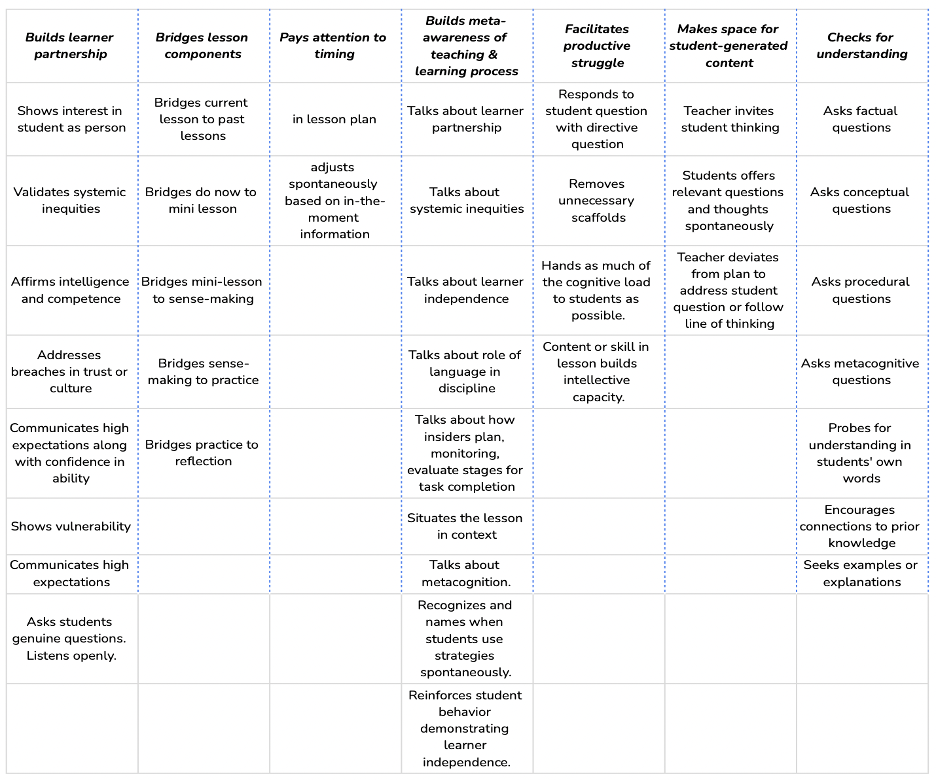

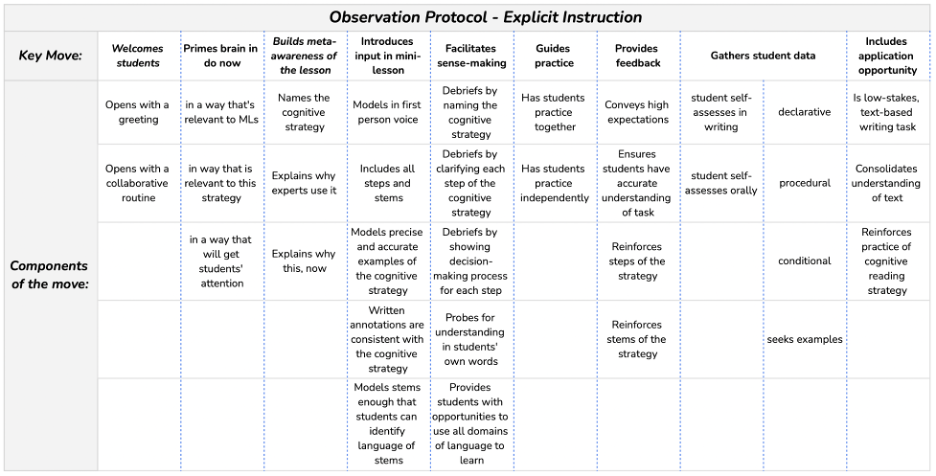

Using an observation protocol

Guiding the debrief conversation was an observation protocol which describes the key instructional moves that are supportive of multilingual learners’ language and literacy development (see Figure 5). The observation protocol was designed to support teachers’ pedagogical shifts by providing them a curated set of high-leverage, evidence-based moves to integrate into their practice. Each of the moves included a set of components (micro-processes) to support teachers in enacting the move with maximum fidelity and effectiveness.

Engaging in ongoing written reflection

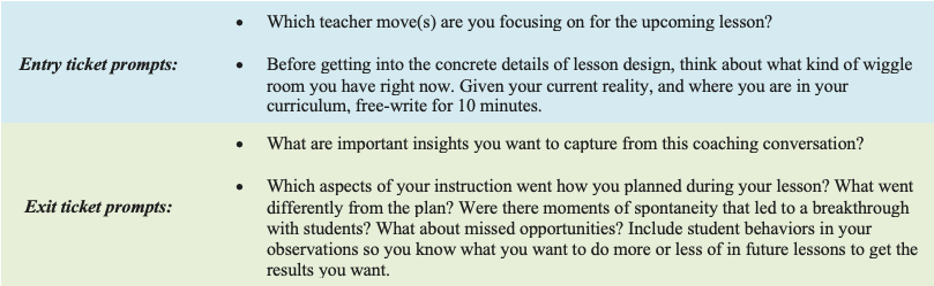

A practicum journal was used as a companion tool for teachers to use alongside the observation protocol and program resources. The journal was structured around nine observations and coaching visits during the school year and provides teachers with an opportunity to engage in reflective practice through a set of prompts.

The practicum journal was organized using entry and exit tickets. Teachers would journal in advance of an observation and coaching visit, and would also synthesize takeaways in an exit ticket following the visit. Figure 6 shows examples of journal prompts that were used in the practicum.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that having an instructional coach that focuses on building teacher and student relationships, embeds strengths-based perspective, and uses classroom observations and written reflections to guide teacher discussions are key components to growing teachers’ skills and shifting their practices to better support multilingual learners in their classrooms. We recommend that school and district leaders support sustained engagement between coaches and teachers by building in at least 5–6 classroom visits from coaches per year in order for coaches to get to know teachers’ strengths and to form trusting relationships.

Limitations to our study

In studying these key components of coaching, we do want to recognize that there are limitations to our study. Disruptions caused by the pandemic shifted how coaches, teachers, and students were able to interact, and the data we were able to collect. In the future, we do hope to look at the long-term impact of the program on teacher practice and any shifts in practice at the school level in supporting ML students.

References

Chi, M. (1997). Quantifying qualitative analyses of verbal data: A practical guide. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 6(3), 271–315. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0603_1

Frey, N., & Fisher, D. (2011). Guided Learning: Questions, Prompts, and Cues: Leading students to think through their own misunderstandings is a powerful way to teach. Principal Leadership, 11(5), 58–60.

Hammond, Z. L. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin Press.

Kim, J. S., Olson, C. B., Scarcella, R., Kramer, J., Pearson, M., van Dyk, D., Collins, P., & Land, R. (2011). Approach to text-based analytical writing for mainstreamed Latino English language learners in grades 6 to 12. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 4(3), 231–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2010.523513

Knight, J. (2017). The impact cycle: What instructional coaches should do to foster powerful improvements in teaching. Corwin Press.

Knight, J. (2019). Instructional coaching for implementing visible learning: A model for translating research into practice. Education Sciences, 9(2), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020101

Lindsey, D. B., Martinez, R. S., Lindsey, R. B., & Myatt, K. T. (2019). Culturally proficient coaching: Supporting educators to create equitable schools. Corwin Press.

Matuchniak, T., Olson, C., Scarcella, R., (2013). Best Practices in teaching writing to English learners: Reducing constraints to facilitate writing development. In S. Graham, C. MacArthur, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Best practices in writing instruction (2nd ed., pp. 381–402). The Guilford Press.

New York City Department of Education. (2019). 2018-2019 English language learner demographics report. New York City Department of Education Division of Multilingual Learners. https://infohub.nyced.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/ell-demographic-report.pdf

Olsen, C. B., & Land, R. (2007). A cognitive strategies approach to reading and writing instruction for English language learners in secondary school. Research in the Teaching of English, 41(3), 276–278. Retrievable from https://publicationsncte.org/content/journals/rte/

The Nation’s Report Card. (2022). NAEP report card: Reading. Accessed 16 June 2023 at www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading/nation/achievement/?grade=8