Bonnie Swierzbin

Demonstratives (this, that, these, those) fundamentally mean “pay attention”. In conversational language, as typically taught in ESL textbooks, demonstratives work with gestures to point listeners to objects, sounds, etc. in the current environment. But in academic lectures, demonstratives often tell listeners to pay attention to more complex entities such as ideas, events, and situations. They create reference chains that help listeners understand and synthesize the big picture of a lecture. ESL instructors need to teach the functions of demonstrative reference that occur in academic language.

Keywords: grammar, demonstratives, text cohesion, college, university, teacher education

Demonstratives (this, that, these, those) tell the listener to pay attention, but what to pay attention to (the referent) can vary greatly, depending on the discourse situation. The basic, everyday use of demonstratives is pointing to someone or something at the moment of speaking, and this use is what is most commonly taught in English as a Second Language (ESL) textbooks (Schiftner & Rankin, 2012). But as Lawson (2001) observes, demonstratives have physical referents only when objects and people are the main topics of discussion, for example, in conversations, narratives and factual recounts. However, other language genres, such as historical recounts, explanations, and discussions, are likely to have ideas and events as topics of discussion, and here, the referents of demonstratives are frequently represented by linguistic forms (phrases, clauses, sentences) more than physical ones (Lawson, 2001). Certainly, referring to ideas and events happens in conversations (e.g., This is fun! while riding a roller coaster), but the frequency of referent type may vary by genre (Peeters, Krahmer, & Maes, 2020).

Looking at academic language, Example 1a shows demonstrative pronoun this referring to the event expressed in the entire preceding sentence. In Example 1b, the academic lecturer uses demonstrative pronoun this to refer to the idea stated over several dependent clauses regarding how LSD produces hallucinations.

1a. Pericles strengthened Greek democracy by increasing the number of paid public officials and paying jurors. This enabled poorer citizens to participate in the government. (Beck, Black, Krieger, Naylor, & Shabaka, 2012)

1b. Okay, so little bit about the sort of progression of research on how serotonin is influencing, or how LSD is influencing, or thought to influence, serotonergic neurotransmission, to produce hallucinatory effects. Now the very, very first studies that were done on this back in the fifties…

As illustrated in these examples, demonstratives provide a concise and efficient way to refer to ideas and events that are potential discussion topics; however, the topics themselves are often expressed by relatively long, complex sentences or sets of clauses. These linguistic forms may also represent other potential referents for the demonstratives, democracy1 in the first example and research, serotonin, LSD, and serotonergic neurotransmission in the second. These other potential referents are not likely to distract English native speaker (NS) listeners; research has indicated that NS listeners tend to resolve demonstratives as referring to complex entities such as ideas and events while tending to resolve personal pronouns as referring to simple concrete entities represented in noun phrases (Wittenberg, Momma, & Kaiser, 2021). However, English learners may have difficulties if they have only been taught that demonstratives refer to physical entities. Unfortunately, research on how these learners process demonstratives is sorely lacking.

English learners are very likely to have heard the demonstrative pronoun that refer to an idea when instructors evaluate an idea stated by a student (Example 2).

2. S: Giraffes have long necks.

T: That‘s true.

This example shows a relatively simple way a demonstrative can refer to an idea, but it is not clear if hearing such interactions in the classroom helps learners understand more challenging ways demonstratives are used in academic language. Authentic materials drawn from actual academic lectures are rich in examples of demonstratives that are not normally found in materials developed for teaching purposes or in simple instructor-student interactions. Academic lectures are central to university-level teaching and learning, but comprehending lectures can be particularly hard for English learners (Dang & Webb, 2014, Hyland, 2009). Such difficulty can be due to many factors, including specialized vocabulary and rhetorical structure. In addition, second language listeners tend to listen for content words instead of function words such as demonstratives, prepositions, and auxiliary verbs (Field, 2008), and while that is a helpful listening comprehension strategy, students also need to track reference chains through the ideas that are introduced and discussed in academic lectures, and this is where demonstratives make a crucial contribution. The present article is intended to shine a light on how demonstratives are used in oral academic lectures so ESL instructors can prepare learners for what they are likely to hear. Following some basic information about English demonstratives, this study presents a review of typical ways that demonstratives are used in university-level academic lectures. The examples are drawn from two academic lectures given by native speakers of American English (one female and one male) in the Biological and Health Sciences division of the University of Michigan. The lecture topics were Drugs of Abuse and an Introduction to Evolution.

Basic info about demonstratives

The words that and this are considered part of a basic 2000-word English vocabulary, and demonstratives that, this, those, and these are, respectively, the eighth, forty-fifth, 122nd and 135th most frequent words in the Cambridge English Corpus, based on a sample of four and a half million words of conversation (McCarthy, McCarten, & Sandiford, 2014). In addition to being a demonstrative, that has other functions such as introducing adjective clauses (the dog that belongs to Shohei Ohtani) and noun clauses (Dwight thought that yesterday was Thursday), making its usage far more common than this, these, and those. In the current study, only the demonstrative uses of this, that, these, and those will be discussed.

The common use of demonstratives to refer to people and objects in the real world is a type of exophoric reference; that is, the referents are in the external world outside the text (oral or written). Referring expressions may also point to referents in the text itself, in which case they are termed endophoric. Example 3, from a university-level Intro to Evolution lecture, illustrates the types of references. During the lecture, images (similar to Figure 12) were shown via an overhead projector, and the first word of the example text (3a) is an exophoric reference to an image.

3. This (a) is a frigate bird, and the male frigate bird has this (b) big red throat patch, which normally you can’t see very well at all. It’s just kind of tucked in, but this (c) picture shows him with it inflated out like this (d) because he’s trying to attract a female frigate bird. <2 omitted clauses> Since females have been choosing males with these (e) big red throat patches, the big red throat patched males have more offspring, and so those (f) with bigger and better red throat patches have more offspring, and so we get over generational time more and bigger throat patches on these (g) frigate birds. So the selective pressure has come from the females’ choice, the female is making the choice. The problem… So we first of all have usually, is female choice, and again we’ll talk about that (h) next week.

In the first two sentences3, this is used for exophoric reference three times (a, c, and d), referring to the image or possibly the lecturer’s gesture (out like this), and for endophoric reference once (b), introducing new information that the lecturer intends to continue talking about. As this section of the lecture proceeds, the lecturer moves from presenting specific birds in the first two sentences to discussing frigate birds generically in the third sentence, and finally to the abstraction female choice at the end. With the move to abstraction comes a shift in the way demonstratives are used; specifically, that (h) in the final sentence is an endophoric reference to the idea female choice (or perhaps, the problem…is female choice), which is expressed in the previous clause. It’s natural that the lecturer would introduce an idea and then, as she continues talking about it, refer to it with a demonstrative, but some potential problems arise for English learners: The referent of that is an idea, not something the students can see, and the referent is somewhat unclear. Lack of clarity is common with textual demonstrative pronoun references (Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad & Finegan, 1999), which has led any number of English instructors to forbid them or place substantial restrictions on their use (Crovitz & Devereaux, 2017). Despite such strictures, Examples 1 (a & b), 2 and 3 (h) show that such usage is still quite common in academic settings. Thus, ESL instructors need to be prepared to teach how demonstratives are used beyond simple pointing.

What demonstratives do in university-level academic lectures

Grammatical categories

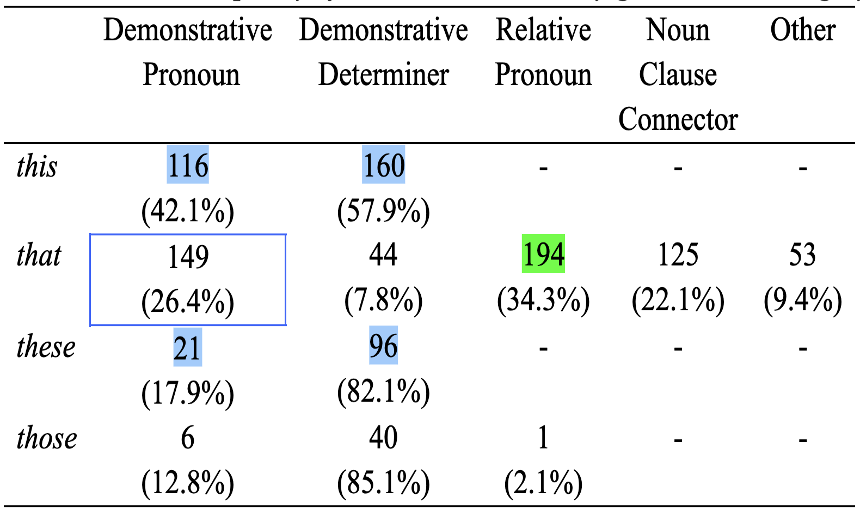

Before focusing specifically on demonstratives, this section provides a brief overview of the grammatical categories of this/that/these/those in the academic lectures that were analyzed. The highlighted cells in Table 1 show that this and these were used exclusively as demonstratives while that was used most frequently as a relative pronoun (as in the announcement that I made). Even when it was a demonstrative, the usage of that also differed from other demonstratives in the lectures: The boxed cell shows that that was most frequently a pronoun (that‘s a reminder) while all the other demonstratives were most frequently determiners (these frigate birds).

The variety of categories for that offer an initial hint at a teaching strategy: The demonstrative pronouns and determiners will be slightly stressed while clause connectors for relative clauses and noun clauses will be unstressed (Lane, 2010). Stress differences can also help distinguish the functions of demonstratives, which will be discussed in the next sections.

Functional categories

This paper discusses three functional categories for demonstratives in academic lectures.4 Demonstratives often function to refer to something visible or audible in the current context or to introduce something into that context; these are exophoric references and this function is called situational (Himmelmann, 1996). The tracking function of demonstratives (Himmelmann, 1996) is used to continue referring to something already mentioned; this is a type of endophoric reference. The discourse deixis function, also endophoric, occurs when a speaker refers to events or propositions rather than people and physical objects.5

Function: Situational

In the academic lectures analyzed in this study, the demonstrative pronoun this was often used to refer to something visible in the context of the lecture, typically a slide (see Example 4a) or part of a slide (Example 4b).

4a. This is just showing the application of serotonin itself.

4b. The red things are supposed to represent serotonin receptors, so this would be a serotonin autoreceptor.

Demonstrative pronoun that, on the other hand, rarely referred to something visible in the lecture context and when it was used that way, it referred to something just recently visible. Example 5 occurred when the lecturer was showing a series of animals with low genetic variability and seemed to have quickly passed by a slide with a panda.

5. That was a panda obviously just before this is um, a Florida panther and its cub, and I think that there’s less than a hundred of these left, and the cheetah, of course.

When referring to something in the current context, demonstrative determiner this tended to be used in two different ways by the two lecturers. In the Drugs of Abuse lecture, demonstrative this was usually used to refer to all or part of a slide image. In contrast, in the Introduction to Evolution lecture, it was more often used as an indefinite this (see Example 6), perhaps because the lecturer was telling a relatively informal narrative of Darwin’s early life, introducing and describing new characters and entities.

6a. Then he got outta college and he got this really great job offer.

6b. Alfred Russel Wallace was this really poor uneducated guy.

ESL students may encounter indefinite this in informal contexts, but it is rarely presented in ESL textbooks, so helpful teaching strategies would include pointing out instances of indefinite this as well as directing students’ attention to the verbal and visual cues that distinguish uses of this referring to something identifiable in the current context versus indefinite this, introducing something into that context. Specifically, instructors can help students listen for stress on the determiner (pointing) versus stress on the noun (indefinite this) and watch for pointing gestures versus no pointing gesture (indefinite) (Gernsbacher & Shroyer, 1989).

Function: Tracking

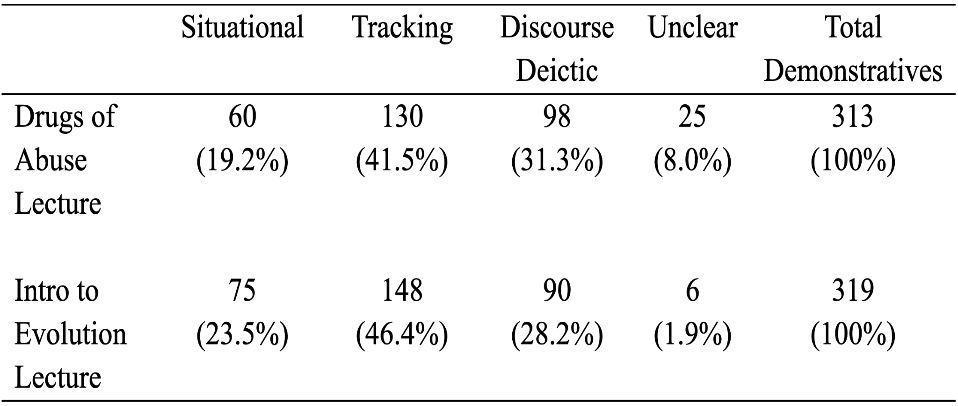

Tracking, which occurs when a demonstrative refers to people and entities already established in the discourse, was the most frequent function of demonstratives in the analyzed academic lectures (see Table 2).

The simplest kind of tracking is shown in Example 7(a), where the head noun, essence, in the referent is repeated with a demonstrative determiner in the next two clauses. A second, relatively obvious, kind of tracking also occurs with demonstrative determiners and is shown in 7(b). Here the speaker used the class of the noun evolution to refer to it as this idea and then used a synonym, concept, to refer to it a second time. The reference chain in 7(a) involves simple repetition while the chain in 7(b) requires deeper semantic knowledge.

7a. So we each had our own individual essence, and as thinking beings we’re supposed to try to understand this essence, and therefore variation from this pure essence is uninteresting.

7b. Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution, one famous biologist said. Because without this idea of how things change over time and how everything is descended from an original organism, essentially, without that concept you can’t possibly begin to figure out how all this diversity came about.

In the lectures, tracking also occurred with demonstrative pronouns (see Example 8a & b). In these examples, the referent is in the immediately preceding clause, making their referents relatively easy to find.

8a. The first one is called uniformitarianism, and that means that there are uniform processes that occurred a long time ago and are still occurring and will continue to occur.

8b. This is sort of a standard way to look at these kind of things and I’ve showed you examples of this in other systems.

However, as shown in Examples 9 & 10, the referent of a tracking demonstrative can be further away. Demonstratives can be used to signal the focus on a higher-level topic (Cornish, 2018), which can be more difficult for listeners to process since the topic may not have been mentioned in the immediately preceding clause. In fact, Example 9 from the Intro to Evolution lecture shows that the higher-level topic, diversity of life, was not mentioned for more than ten clauses.

9. I just started out with some pictures here, to just remind you, of the incredible diversity of life on this planet and the diversity of life that has since disappeared, all the things that have gone extinct. <10 omitted clauses with no use of the term ‘diversity’> because without this idea of how things change over time and how everything is descended from an original organism essentially, without that concept you can’t possibly begin to figure out how all this diversity came about.

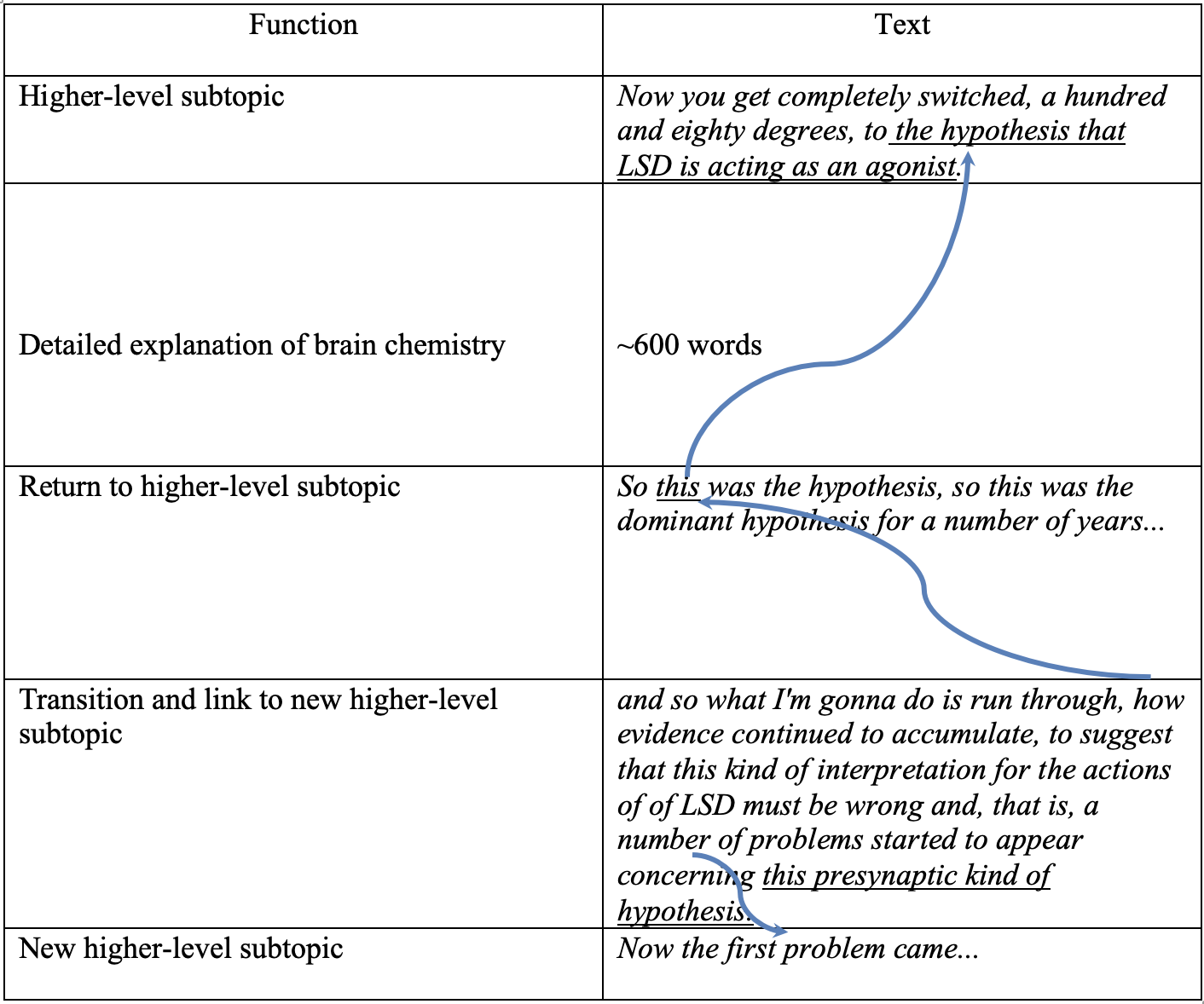

Example 10 comes from the Drugs of Abuse lecture, in which the lecturer was explaining how hallucinogens work in the brain. In the lecture, he works his way through several hypotheses, which are higher-level subtopics of the lecture. But just prior to the quote in Example 10, he had used ~600 words explaining the details of how LSD supposedly works in the brain and had not mentioned any hypothesis.

10. So this was the hypothesis, so this was the dominant hypothesis for a number of years, but people then continued to work on this, and what you’re going to see, in the the next few um examples of how, it very quickly became, well, it actually not all that quickly but over a number of years many years, it became apparent that this can’t be true. This presynaptic hypothesis has gotta be wrong.

The distance from the demonstrative to its referent is noteworthy, but of more interest is how the lecturer used this to indicate the structure of the subtopics in the lecture. Using this to refer back to the most recent hypothesis serves two related functions. First, this indicates that listeners should give more attention to the referent (Strauss, 2002); that is, it is more important than other details mentioned in the 600 words. Second, as shown by the arrows in Figure 2, the text section with multiple uses of this serves to link both backward to the earlier mention of the current subtopic and forward to the next subtopic.

Examples such as these illustrate the importance of ESL instructors using extended authentic text to teach cohesion and coherence as well as including demonstratives when having students construct reference chains.

Function: Discourse deixis

Demonstratives referring to events and propositions, called discourse deixis, is the situation where they make a distinct contribution to the English reference system because such references are made precisely and succinctly with demonstratives. In Example 11, the lecturer states the basic proposition of Plato’s theory of essentialism and then immediately names it, referring to it with a demonstrative. The demonstrative this is key here because this tells the listener to give more attention to the referent (Strauss, 2002) and indicates that the referent is likely to be something more complex than a person or object (Wittenberg, Momma, & Kaiser, 2021). Notice that if the utterance were ‘it was called essentialism’, the referent of it would seem to be essence or thing.

11. If you see things that are a little bit different in nature, just ignore it. It’s the essence of the thing that matters. This was called essentialism.

With discourse deixis, the referent is typically expressed in the previous clause or sentence (Himmelmann, 1996), as shown in Examples 11 and 12, where that refers to the proposition stated in the immediately preceding clause. This is unlike the tracking function, where the referent is often some distance away (Webber, 1991).

12. Now, most of the research on the mechanisms of action of the hallucinogens has focused on serotonin systems, and that of course is because of their structural similarity to the neurotransmitter’s serotonin.

Teaching demonstratives should include noticing activities for their use in multi-paragraph texts such as sections of a textbook or transcripts of conversation (Conrad & Biber, 2009). Noticing demonstratives can be promoted by enhancing (e.g., bolding, highlighting) them in the text, especially because they are not salient forms (Ellis, 2016). The enhanced demonstratives should include judiciously chosen examples of references that are potentially unclear or difficult to process. After a noticing activity, instructors can help students identify the functions of demonstratives by modeling thinking aloud as they try to identify their referents, focusing in particular on tracking demonstratives that contribute to the structure of the text and discourse deictic demonstratives, referring to propositions and events. Texts used for such activities should be authentic and lengthy enough to include a variety of examples. The free corpora listed in the Resources section of this paper are a good place to start exploring texts.

Conclusion

Demonstratives are a form that an instructor of advanced English learners may feel the learners know since the basic use of demonstratives is typically taught in low-intermediate courses. An advanced-level course can usefully build on that basic knowledge to cover the more sophisticated functions of demonstratives described in this article, using examples drawn from language corpora. Exploring these functions also shifts emphasis away from abstract, mostly boring, grammar rules into the more useful and exciting realm of real-world language patterns, thus leaving students better prepared to comprehend academic lectures.

Resources

Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/

Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English (MICASE) https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/c/corpus/corpus?page=home;c=micase;cc=micase

Notes

1. Pericles is also a potential referent although demonstrative pronouns typically refer to animate entities only in restricted circumstances such as introductions, e.g., I’d like you to meet my friends. This is Pericles, and that is Achilles.

2. Public domain image downloaded from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frigate_(46887068965).jpg

3. The example text is a transcript of an audio recording: Intro to Evolution Lecture, Transcript ID LEL175JU154 downloaded from the Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English.

4. More functional categories for demonstratives exist, but are not relevant to the current discussion. See Himmelmann (1996) for a complete account.

5. Discourse deixis has also been called text reference (Fillmore, 1982). Himmelmann’s term covers both text reference and extended reference, as defined by Halliday and Hasan (1976).

References

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., & Finegan, E. (1999). Longman grammar of spoken and written English. Longman.

Conrad, S. & Biber, D. (2009). Real grammar: A corpus-based approach to English. Pearson Education.

Cornish, F. (2018). Anadeixis and the signalling of discourse structure. Quaderns de Filologia: Estudis Lingüistics, 23, 33-57. https://doi.org/10.7203/qf.23.13519

Crovitz, D., & Devereaux, M. (2017). Grammar to get things done. Routledge & National Council of Teachers of English.

Dang, T. & Webb, S. (2014). The lexical profile of academic spoken English. English for Specific Purposes, 33, 66-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2013.08.001

Ellis, R. (2016). Grammar teaching as consciousness raising. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Teaching English grammar to speakers of other languages (pp. 128-150). Routledge.

Field, J. (2008). Bricks or mortar: Which parts of the input does a second language listener rely on? TESOL Quarterly, 42(3), 411-432. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00139.x

Fillmore, C. (1982). Towards a descriptive framework for spatial deixis. In Jarvella, R. & Klein, W. (Eds.), Speech, place and action (pp. 31-59). John Wiley.

Gernsbacher, M., & Shroyer, S. (1989). The cataphoric use of the indefinite this in spoken narratives. Memory & Cognition, 17(5), 536-540. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03197076

Halliday, M. & Hasan, R. (1976). Cohesion in English. Longman.

Himmelmann, N. (1996). Demonstratives in narrative discourse. In B. Fox (Ed.), Studies in anaphora (pp. 205-254). John Benjamins.

Hyland, K. (2009). Academic discourse: English in a global context. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Lane, L. (2010). Tips for teaching pronunciation: A practical approach. Pearson Education.

Lawson, A. (2001). Topic management and demonstratives in spoken English and French: A corpus-based approach [unpublished Ph.D. dissertation]. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

McCarthy, M., McCarten, J., & Sandiford, H. (2014). Touchstone: Teacher’s edition level 3 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Peeters, D., Krahmer, E., & Maes, A. (2020). A conceptual framework for the study of demonstrative reference. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 28(2), 409-433. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-020-01822-8

Schiftner, B. & Rankin, T. (2012). The use of demonstrative reference in English texts by Austrian school-age learners. In Y. Tono, Y. Kawaguchi & M. Minegishi (Eds.), Developmental and crosslinguistic perspectives in learner corpus research (pp. 63-82). John Benjamins.

Strauss, S. (2002). This, that and it in spoken American English. Language Sciences, 24, 131-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0388-0001(01)00012-2

Webber, B. (1991). Structure and ostension in the interpretation of discourse deixis. Language and Cognitive Process, 6(2), 107-135. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.cmp-lg/9708003

Wittenberg, E., Momma, S., & Kaiser, E. (2021). Demonstratives as bundlers of conceptual structure. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 6(1), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.917

Appendix: Data sources

Beck, R., Black, L., Krieger, L., Naylor, P., & Shabaka, D. (2012) Modern world history: Patterns of interaction. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved from https://my.hrw.com/SocialStudies/ss_2010/downloads/htmlfiles/content/Modern_World_History_Unit_1.pdf

Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English, English Language Institute, University of Michigan (2001). Intro to Evolution Lecture [data file]. Retrieved from https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/c/corpus/corpus?c=micase;cc=micase;view=transcript;id=LEL175JU154

Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English, English Language Institute, University of Michigan (2001). Drugs of Abuse Lecture [data file]. Retrieved from https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/c/corpus/corpus?c=micase;cc=micase;view=transcript;id=LEL500SU088