The Community English Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham provides free English classes to adult learners from the international community. Housed in the School of Education for the past decade, this program serves as a “lab” school with a standards-based language curriculum taught by MA-TESOL students. By reflecting on how this lab school developed, we identify strategies for ongoing improvement.

Keywords: adult learners, lab school, standards-based curriculum, strategies, ongoing improvement, international community, free English classes

Ten years ago, budget cuts and institutional restructuring threatened to eliminate English conversation classes, a free service provided for over two decades by the International House at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). We, as English as a Second Language (ESL) faculty in the School of Education (SOE), were shocked at this pending loss and immediately sought a solution. The SOE secured these English classes and housed them in the Education Building. We restructured these classes with the dual purpose of meeting the language learning needs of international adults from the university community and greater metropolitan area and of meeting the language teaching needs of graduate students from the adult track of a new ESL master’s degree.

Perceiving a need, preserving a service

By responding quickly to a perceived need, we, along with our SOE administrators, saved the English conversation classes. The ensuing Community English Program (CEP) has served as a laboratory school for two stakeholder groups: (1) students in the master’s in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (MA-TESOL) who become skilled in their chosen career by teaching English to adult learners, and (2) adult learners from over 50 countries who receive free, high-quality English language classes. These CEP learners represent diverse nationalities, languages, educational backgrounds, age, socioeconomic status, and motivation. They have included UAB employees such as medical researchers and visiting professors as well as employees’ spouses, parents, and other family members. For example, we vividly remember a retired chemistry professor and his wife from Syria who, though visiting their son—a UAB professor, were unable to return home due to an escalating war. CEP learners from the greater metropolitan area exemplify greater diversity such as a group of technology specialists from Colombia who were employed at an international bank’s regional headquarters. Young adults have also participated in CEP classes. We fondly remember the many au pairs from Europe, Brazil, Colombia, and Japan, as well as an Afghan woman who, with limited formal schooling, wanted to learn to read. Our CEP learners also include restaurant employees, construction workers, landscapers, and day laborers; among all these learners are recent arrivals and those who have lived in the United States for decades.

Now, at the 10-year anniversary of our lab school, we reflect on how the dual-purposed CEP supports both international adult English learners and MA-TESOL students learning to be teachers. From among criteria for successful language program administration (Stoller, 1997; TESOL, 2002), we have identified several strategies that have supported this dual purpose and offer insights for their application. These strategies include recognizing changes as they emerge, connecting needs of various stakeholders, linking practice to educational standards, innovating adjustments when faced by unusual circumstances, and planning strategically for the future.

Recognizing changes, developing opportunities in the learning landscape

UAB began offering TESOL methods courses in 1999. This led to an ESL certification program that included K-12 clinicals for teaching English learners. In 2005, some of our potential applicants wanted a path for learning to teach ESL to adult learners. To meet their need, we piloted an “adult option” in an existing master’s degree. For their adult clinicals, these graduate students taught weekly classes at UAB’s International House, the Literacy Council of Central Alabama, community colleges, ethnic centers, and/or faith-based entities (DeRocher et al., 2015). To determine their placements, we considered career goals and available settings (Spezzini et al., 2016). For instance, if graduate students wanted to prepare for teaching academic English, we would arrange their final clinical at UAB’s English Language Institute.

In 2011, two pivotal events opened new opportunities in this learning landscape. In March 2011, we received state approval to launch a master’s degree in ESL. This degree’s third track, called MA-TESOL, was for teaching ESL to adult learners and, as such, needed to align courses with clinicals in adult settings (Spezzini & Olmstead-Wang, 2013). In June 2011, we learned that the International House was charged with discontinuing its English conversation classes. To save these classes, both as a valuable campus legacy and as a clinical venue for teaching adults, we provided a new home for these classes. Literally overnight, we moved the English conversation classes to the SOE with summer classes starting the next day, as planned, but in a different place.

Linking and connecting needs of various stakeholders

A decade ago, we had the foresight to save UAB’s English conversation classes. Though not knowing what the future might bring, we imagined these classes as evolving into a more extensive effort in concert with Standards for Adult Education ESL Programs (TESOL, 2002) and Standards for ESL/EFL Teachers of Adult Learners (TESOL, 2008). Now named CEP, this evolving initiative has more thoroughly incorporated the learning needs of an existing constituency and served as a laboratory school to prepare future ESL teachers (Spezzini et al., 2015). Redesigning programs and clinical experiences: Bridging theory to practice. Paper presented at 49th annual International TESOL Convention. Toronto, ON, Canada). Our goal has always been to provide quality language classes to international adults from UAB’s greater community in a venue where MA-TESOL students could gain quality teaching experience, hone their teaching skills, expand their repertoires of teaching techniques, and benefit from regular, sequenced, professional feedback from SOE mentors.

During these past 10 years, our MA-TESOL students have taught CEP classes weekly, starting in their first semester and ending in their fifth and final semester. We pair MA-TESOL students who have no previous teaching experience as co-teachers with other MA-TESOL students who have experience teaching CEP classes. The MA-TESOL students with previous experience in teaching ESL to adults often skip this co-teacher phase and immediately start teaching their own CEP class. Our expectation is for all MA-TESOL students to have taught at least four different levels of CEP classes before graduating.

After establishing the CEP in the SOE, we converted loosely structured conversation classes into tightly structured classes where adult learners could develop all language modalities, thus more closely meeting the standards of adult ESL programs (TESOL, 2002, 2008). Honoring the premise that language is a social tool, the CEP promotes Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) (Richards & Rodgers, 2014) as its overarching approach towards language teaching and learning. To that end, CEP teachers are expected to use authentic materials and to develop learner-centered activities that build meaning. For language learning goals, they aim to develop multiple competencies such as grammatical competence, sociolinguistic competence, strategic competence, and discourse competence (Canale & Swain, 1980). Through this CLT approach, our CEP teachers also implement Task-Based Language Teaching (Richards & Rodgers, 2014) by focusing on real-world situations. The theories, methods, and techniques used by these CEP teachers for teaching classes are formally linked with the MA-TESOL program through projects and other activities assigned in their second language acquisition and methods courses.

CEP’s development also included iterative steps for blending two cultures of learning—the culture of community language learners and the culture of novice English teachers. We established sequences for placing MA-TESOL students as CEP teachers, developed rubrics to professionalize the training of these CEP teachers, and then upgraded these rubrics to better assess teacher progress. Now, by the CEP’s 10th anniversary, we have an articulated mission statement, flexible class schedules, multiple locations to meet learner needs, and a teacher-learner ratio of about 1 to 6. We also have access to SOE facilities and resources, clear and confidential communication among stakeholders, and an enhanced record keeping system to track English learners’ progress through integrated levels.

Linking education standards and practice, scaffolding to meet demands of best practices

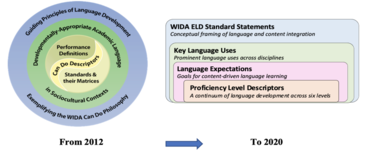

The CEP curriculum has evolved over time. Our most recent curriculum team, which was convened in Summer 2020, consisted of SOE faculty and MA-TESOL students. With the goal of updating our earlier CEP curriculum, this 2020 team based the newly emerging curriculum on the English Language Proficiency Standards for Adult Education (U.S. Department of Education, 2016). This curriculum team adapted language learning outcomes for each level, provided sample assessments to meet a variety of standards, and prepared learning rubrics to determine whether language learners had mastered sufficient skills for moving to the next of CEP’s five levels. After several iterations, inclusive of cyclical reflection and feedback, the current CEP curriculum reached full implementation in Fall 2021.

For implementing CEP’s current curriculum, MA-TESOL students design weekly lessons on articulated standards and on learner interests, levels, and needs. In their role as CEP teachers, they start each semester by aligning language goals with two or three learning outcomes at the corresponding language level (Prado et al., 2020). On the first day of each semester, all CEP teachers conduct a needs assessment questionnaire and identify content that interests their respective learners. They design their lessons with authentic materials and appropriate technology for engaging these adult learners in interactive learning techniques to develop all four language domains. They align content with learning outcomes so that their CEP class becomes a learning community with a “destination” for the semester (Prado et al., 2020).

By means of evidence-based standards, regular assessment ensures that programs meet benchmarks and conform to best practices. With goals of improving the teaching practice of MA-TESOL students and of supporting language learners, we—as faculty mentors—scaffold the teaching experience for all CEP teachers, but especially for novice teachers and those who are new to the program. Each semester, CEP teachers participate in an orientation session, a mid-semester check-in, and a final wrap-up meeting. These meetings are touch points for questions and concerns. During these meetings and, as needed, throughout the semester, these teachers receive guidance on topics ranging from recommended co-teaching practices (Cook & Friend, 1995; Dormer, 2012) to CEP administrative tasks. Co-teachers share in writing weekly lesson plans and in receiving feedback. In addition, the CEP coordinator observes teachers and provides feedback on the observed teaching episodes.

Language proficiency standards (U.S. Department of Education, 2016) have guided CEP teachers in providing essential scaffolding and other support for CEP learners who, as adults, need language skills for many different environments. Our new CEP curriculum meets Standards for Instruction (U.S. Department of Education, 2016) and, as such, includes instructional activities that adhere to principles of adult language learning and approaches for learners from diverse educational and cultural backgrounds. Activities encourage participatory learning and the acquisition of communication skills through interactive group tasks.

The CEP also meets the standard related to learner recruitment, intake, and orientation (U.S. Department of Education, 2016). Intake procedures accurately assess learner levels, needs, and goals. The CEP also meets standards of retention and transition, assessment and learner gains, support services, and professional development. Because the CEP is a lab school, the standard on teaching evaluation is one of its major cornerstones. However, also because it is a lab school, the CEP’s organizational structure does not directly relate to the standard on employment conditions. Nonetheless, to prepare MA-TESOL students for real-world contexts following graduation, we attempt to replicate an employment setting as closely as possible, especially regarding work ethic and performance expectations.

Innovating in emerging circumstances, planning strategically for future contingencies

Flexibility and adaptability are necessary skills for dealing with new circumstances. As ESL faculty, we were flexible in 2011 when inheriting the English conversation classes and converting them into the CEP. We were again flexible in 2019 when incorporating graduate students from the SOE’s new Educational Specialist (EdS) degree in TESOL. As a post-MA degree, the EdS-TESOL attracts experienced ESL professionals, who, as such, bring well-honed teaching skills. By further adapting our existing CEP structure, we included a lead teacher role and incorporated these EdS-TESOL students as lead teachers. By doing so, we provided these TESOL professionals with a coaching experience through which they could demonstrate a competency required in their advanced degree program. As EdS-TESOL students, these professionals provide weekly coaching to novice CEP teachers. This is yet another example of how the CEP’s flexibility and adaptability have benefitted multiple stakeholders of the past, present, and future.

CEP exhibited a different type of flexibility when adapting to the challenges and disruptive factors stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic. Across the world, this pandemic required an immediate transition from face-to-face (F2F) environments to virtual environments. For the CEP classes, this adaptation involved three stakeholder groups: the SOE’s ESL faculty, the CEP teachers (i.e., MA-TESOL and EdS-TESOL students), and the adult language learners. At UAB, all three groups were relatively new to the online teaching and learning of languages. Fortunately, we—the ESL faculty—had begun transitioning our graduate courses to online in 2019. Based on these experiences, we shared our new skills acquired from creating fully online graduate courses with CEP teachers as they transitioned to teaching English online.

When UAB’s campus closed F2F teaching, we needed to strengthen our graduate students’ knowledge and skills in the online teaching of language. Garrison et al.’s (2000) seminal theory, Community of Inquiry (COI), led CEP to reimagine an online learning community with overlapping COI facets: social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence (Prado et al., 2020). According to Garrison et al. (2000), building a social presence consists of both the teacher and the learners authentically interacting and presenting multiple facets of themselves. Likewise, cognitive presence is based on critical thinking but also depends on building meaning through authentic, consistent interactions. The teaching presence is two-fold. As the course designer and learning organizer, the teacher is responsible for presenting an engaging, authentic learning experience. The second component, course facilitation, is shared with learners. In building COI as a community for reciprocal teaching and learning, both the teacher and the learners discuss, question, and problem-solve.

To contextualize COI (Garrison et al., 2000) for language teaching, we integrated principles from second language acquisition. For teaching English learners online, Li (2013) recommends that teachers maintain comprehensible input, relate student learning to the real world, promote social interaction, and facilitate a welcoming learning environment, all of which broadly overlap with COI. These concepts guided our CEP discussions in summer 2020 when MA-TESOL students earned their clinical credit by locating resources for online language teaching and helping design an online curriculum for the CEP classes (Prado et al., 2020). These efforts culminated in an online handbook for CEP teachers, available on our CEP website at https://www.uab.edu/education/esl/community-english-classes.

In adherence with UAB mandates, we and the CEP will continue adapting to new challenges for a safe reopening of F2F classes while maintaining strong links to standards, technology improvement, and record-keeping software. Moreover, after we return to physical classrooms, the CEP will continue to provide online classes to language learners who request the convenience and safety of virtual instruction. Having surfaced from a pandemic-induced opportunity, these online classes are now included among the CEP’s regular class offerings.

Reflecting back, looking ahead

During the past decade, we responded to challenges facing our CEP lab school with flexibility, adaptability, and a forward-looking perspective. At strategic historic moments, we transitioned English conversation classes into the CEP, welcomed EdS-TESOL students to serve as lead CEP teachers, and converted classes to online instruction. Originally based on Standards for Adult Education Programs (TESOL, 2002) and on Standards for ESL/EFL Teachers of Adults (TESOL, 2008) and with a curriculum aligned to English Language Proficiency Standards for Adult Education (U.S. Department of Education, 2016), the CEP now also aligns with The 6 Principles for Exemplary Teaching of English Learners: Adult Education and Workplace Development (Hellman et al., 2019). Together, these standards and principles provide benchmarks for assessing CEP strengths and overcoming challenges. Guided by these benchmarks, the CEP will continue meeting the dual purpose of (1) providing clinical placements for MA-TESOL students to teach adult learners and (2) offering free, high quality English classes to international members of the extended UAB community.

Upon reaching our lab school’s 10-year milestone, we have identified key strategies of language program administration (Stoller, 1997; TESOL, 2002) used to make transitions, initiate improvements, and build for the future. These strategies include identifying opportunities, pivoting directions, reorganizing program components, linking the needs of constituencies to best practices and learning standards, and converting challenges into innovations. By continuing to use these same strategies and adjusting as needed, we look ahead to ushering the CEP into its second decade.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Julia S. Austin for her contribution to the CEP and for her help with this article.

References

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretically bases of communicative approaches for language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1-47. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/I.1.1

Cook, L., & Friend, M. (1995). Co-teaching: Guidelines for creating effective practices. Focus on Exceptional Children, 28(3), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.17161/foec.v28i3.6852

DeRocher, L., Spezzini, S., & Prado, J. (2015, March). Adult learners in community-based ESL classes: Keep ‘em comin’. Paper presented at 49th annual International TESOL Convention, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Dormer, J. E. (2012). Shared competence: Native and nonnative English speaking teachers’ collaboration that benefits all. In A. Honigsfeld, & M. G. Dove (Eds.), Co-teaching and other collaborative practices in the EFL/ESL classroom (pp. 241-250). Information Age Publishing.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Hellman, A. B., Wilbur, A., & Harris, A. (2019). The 6 principles for exemplary teaching of English learners: Adult education and workplace development. TESOL Press.

Li, N. (2013). Seeking best practices and meeting the needs of the English language learners: Using second language theories and integrating technology in teaching. Journal of International Education Research, 9(3), 217-222. https://doi.org/10.19030/jier.v9i3.7878

Prado, J., Spezzini, S., Harrison, M., Fraser Thompson, S., Ponder, J., & Merritt, P. (2020, June). Teacher educator and preservice teacher construct virtual internship through online writing class for post-secondary English learners. In R.E. Ferdig, E. Baumgartner, R. Hartshorne, R.Kaplan-Rakowski, & C. Mouza. (Eds.), Teaching, technology, and teacher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: Stories from the field (pp. 323-327). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://www.learntechlib.org/p/216903

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2014). Approaches and methods in language teaching (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Spezzini, S., & Olmstead-Wang, S. (2013, November). Developing a new track within an existing ESL master’s program. Paper presented at the annual SETESOL conference. Myrtle Beach, SC.

Spezzini, S., Prado, J., & DeRocher, L. (2016, April). Collaborative initiative by three institutions: Preparing ELLs for community college. Paper presented at the 50th annual International TESOL Convention. Baltimore, MD.

Spezzini, S., Seay, S., & Prado, J. (2015, March). Redesigning programs and clinical experiences: Bridging theory to practice. Paper presented at 49th annual International TESOL Convention. Toronto, ON, Canada.

Stoller, F. L. (1997). The catalyst for change and innovation. In M. A. Christison, & F. L. Stoller (Eds.), A handbook for language program administrators (pp. 33-48). Alta Book Center Publishers.

TESOL. (2002). Standards for adult education ESL programs. TESOL Press.

TESOL. (2008). Standards for ESL/EFL teachers of adults. TESOL Press.

U.S. Department of Education. (2016). English language proficiency standards for adult education. Office of Career, Technical and Adult Education. Retrievable from: http://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/elp-standards-adult-ed.pdf