Learn how one district built the foundation for collaborative systems to support multilingual learners with individualized education program (IEPs) with examples from a teacher in the field.

Keywords: disabilities, collaboration, individualized education program, policy

When the authors Kate McNulty, then Director of Bilingual and English Learner (EL) Programming, and Laura Byard, then EL District Program Facilitator, worked in the Minneapolis Public Schools (MPS) Multilingual Department team from 2017–2023, they noticed a common issue that they had experienced in previous roles and as teachers: MPS multilingual learners with individual education programs (IEPs), or twice exceptional students, were often not receiving direct language development instruction. This was despite the framework stating all students who qualify should receive “instruction that is intentional and supportive of English Language Development in alignment with literacy instruction” (Multilingual Department, 2022). A common refrain was “special education [SpEd] services trumps multilingual language development services,” meaning that the framework only applied to most instead of all twice exceptional students. As district leaders, they decided to utilize federal policy to implement systematic changes to English language development (ELD) services for twice exceptional students.

In an attempt to best capture the shift from “SpEd trumps EL” (services for most) to “all means all” (services for all) the authors write this article from two perspectives. The first is the district level perspective of Kate and Laura, and their use of federal policy that initiated three programmatic shifts. The pronoun we will be used to refer to the first perspective. The second perspective is that of Mr. Seth Wester, an ESL teacher at Andersen Middle School, where Laura currently serves as the Multilingual Lead Instructional Coach. Mr. Wester and his practice is an exemplar of these changes. When referring to Mr. Wester’s perspective, we will utilize the pronoun he or refer to him by name. The importance in providing both perspectives illustrates critical coordination between policy at the district level and its implementation within practice at the school level.

Shift #1: Creating a service model

“Given your student’s language background, would you be interested in English Language Development services built into your son’s classroom time?” Seth Wester asked a student’s caregivers in Spanish at an initial evaluation meeting for a new student’s IEP. At Mr. Wester’s school, any multilingual learner who is entering the school with an IEP is discussed as a team in order to provide space in their schedule for direct and explicit language development services. As a result of this intake process, Mr. Wester will provide direct push-in service to the student for one hour each day, five days a week.

On the 40th anniversary year of Lau v. Nichols in 2015, the English Learners Dear Colleague Letter was published in a partnership between the Department of Justice and the Department of Education. Designed to be “guidance to assist [State Education Associates] SEAs, school districts, and all public schools in meeting their legal obligations to ensure that EL students can participate meaningfully and equally in educational programs and services, (U.S. Department of Education & U.S. Department of Justice, 2015 p. 2),” this lengthy document provides a clear path to “all means all” for twice exceptional students.

The Dear Colleague Letter is divided into multiple sections that address several areas in which school districts were non-compliant with their federal obligations to multilingual learners, and in doing so, provides guidance on how to meet those federal obligations. Section F: Evaluating EL Students for Special Education Services and Providing Special Education and English Language Services provided us with the primary compelling reason for redesigning our district-wide service model to include direct service for twice exceptional students. It reads:

School districts must provide EL students with disabilities with both the language assistance and disability-related services to which they are entitled under Federal law. Districts must also inform a parent of an EL student with an individualized education program (IEP) how the language instruction education program meets the objectives of the child’s IEP. (U.S. Department of Education & U.S. Department of Justice, 2015 p. 24-25)

The Dear Colleague Letter lays bare the reality that all qualifying twice exceptional students require both ELD and special education services because they are equally important. Some schools embraced this shift head on, adjusting their schedules and even their teacher allocations to reflect this change. At some high-density sites, this policy was used to justify an entire teacher’s full-time allocation being dedicated to working with twice exceptional students. A site like Mr. Wester’s school is one example: with over 400 multilingual learners and a variety of city-wide special education programs, the school decided it would hire one specific EL teacher to immerse themselves solely in the world of special education and language development.

However, the Dear Colleague Letter alone did not change teacher actions around providing direct services. Common barriers to change were scheduling constraints, a knowledge gap, and simple fear of the unknown (e.g. “How do I teach oracy skills to a student who is nonverbal?”). In fact, we noticed how often students with IEPs were listed as being under teachers’ EL caseloads, but were never actually scheduled for services. Or, the student would have the vague word consult written as their ELD service type. “What can I possibly add?” was often the EL teacher’s response when we pressed for the student to receive direct service. Our starting advice to teachers in this situation: join the classroom community, start to observe learning, and build relationships with the students.

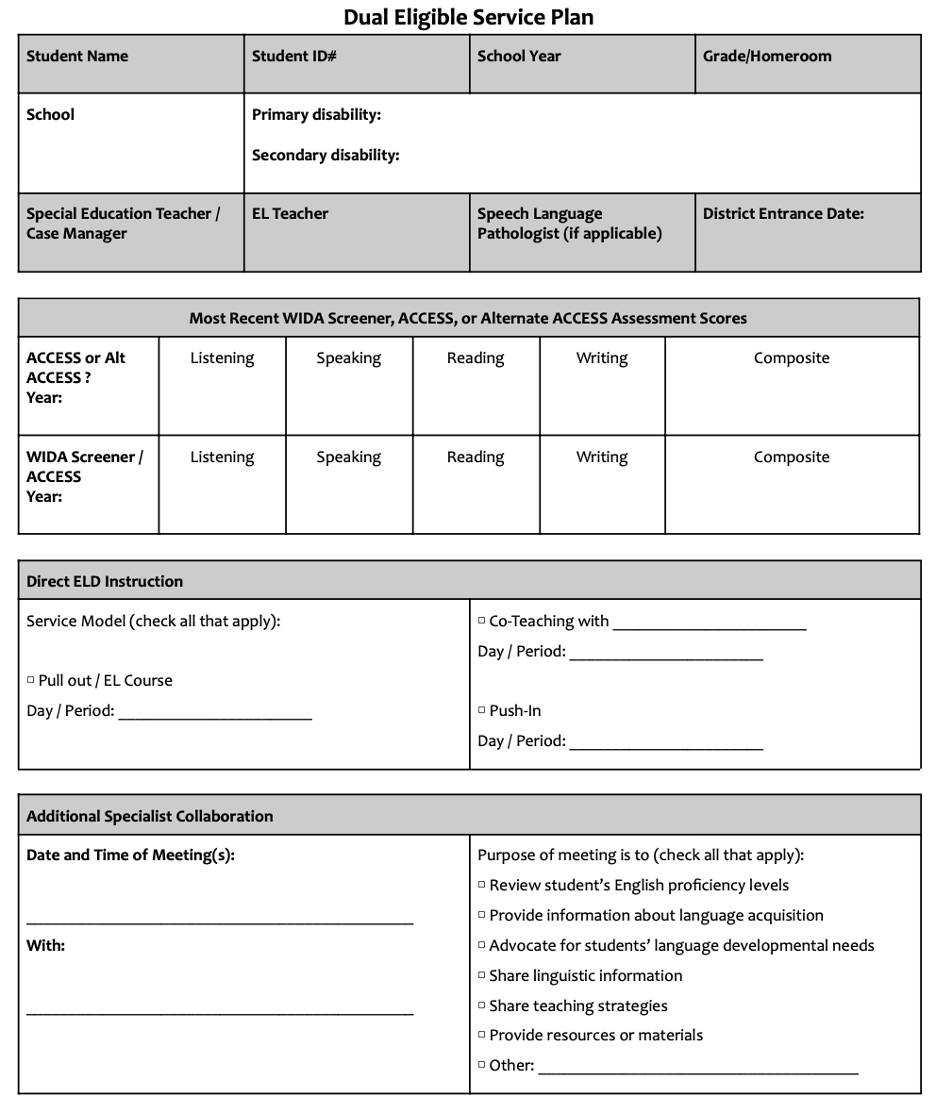

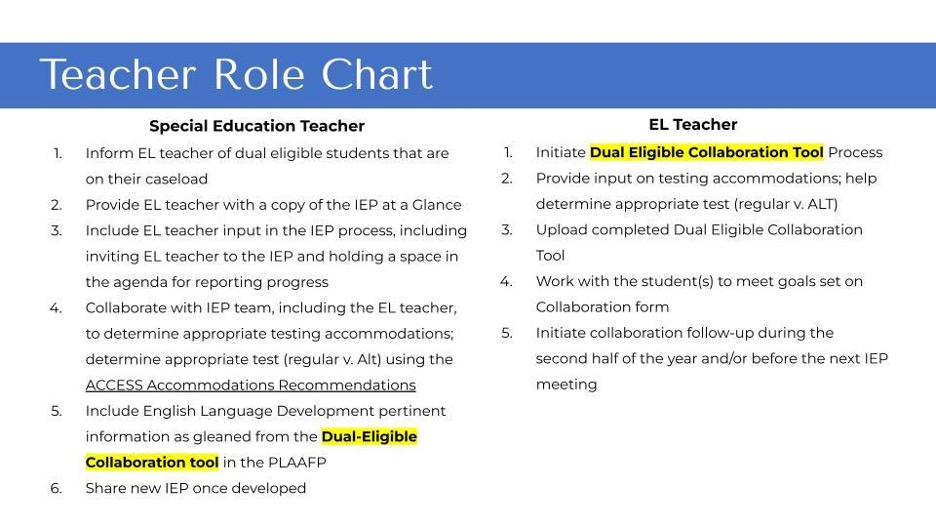

To support teachers in their conversations to determine the scope of ELD services, we created two tools. The first is a service plan (see Figure 1) that documents ELD service foci, teacher collaboration, and their alignment to the IEP plan. The purpose is to document when the student would receive direct instruction, in what format, and to identify other collaborators. The second is a simple teacher role chart to clarify expectations (see Figure 2).

With these two tools, teachers have clearly defined roles of how they can support the student in a way that connects learning and delineates services. Now, at Andersen Middle School for example, when a new student with an IEP enrolls who also receives ELD service, the response is not “SpEd trumps EL” but “When will Mr. Wester work with this student?”

Shift 2: Strengthening teacher collaboration

Early in the school year, Mr. Wester met with the special education case managers of all students who also qualified for EL services. He is the EL teacher for students who do not have English language arts in the general education setting or are in special programs like ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) and DCD (Developmental Cognitive Disability). Mr. Wester had a stack of IEPs that were highlighted anywhere he saw potential crossover with his work as a language development specialist. He asked questions to clarify IEP goals and about the students’ preferred tools for communication. He asked targeted questions like, “How does disability impact the ability to acquire academic and/or functional language?” He asked about the classroom structure, and when and how they worked on different domains of language. He formulated a deeper understanding of how to support individual students, and how to create a sustainable schedule to ensure that all of the students on his caseload would continue to receive attention.

While teacher collaboration is important for all students, it is an especially critical practice for multilingual learners who are twice exceptional. A clear starting point for teacher collaboration is the IEP process (Shyyan et al., 2018). In July of 2014, the U.S. Department of Education authored a Question & Answer guidance document that described expectations around the role of the EL teacher within a student’s IEP process:

It is important that IEP Teams for ELs with disabilities include persons with expertise in second language acquisition and other professionals, such as speech-language pathologists, who understand how to differentiate between limited English proficiency and a disability. The participation of these individuals on the IEP Team is essential in order to develop appropriate academic and functional goals for the child and provide specially designed instruction and the necessary related services to meet these goals. (U.S. Department of Education et al., 2014, p. 6)

Specific to the consideration of language development and its implication in writing an IEP, it adds:

Under the IDEA [Individuals with Disabilities Education Act], the IEP Team must consider a number of special factors in developing, reviewing, or revising a child’s IEP. Under 34 CFR §300.324(a)(2)(ii), the IEP Team must ‘[i]n the case of a child with limited English proficiency, consider the language needs of the child as those needs relate to the child’s IEP.’ Therefore, to implement this requirement, the IEP Team should include participants who have the requisite expertise about the student’s language needs. (U.S. Department of Education et al., 2014, p. 7)

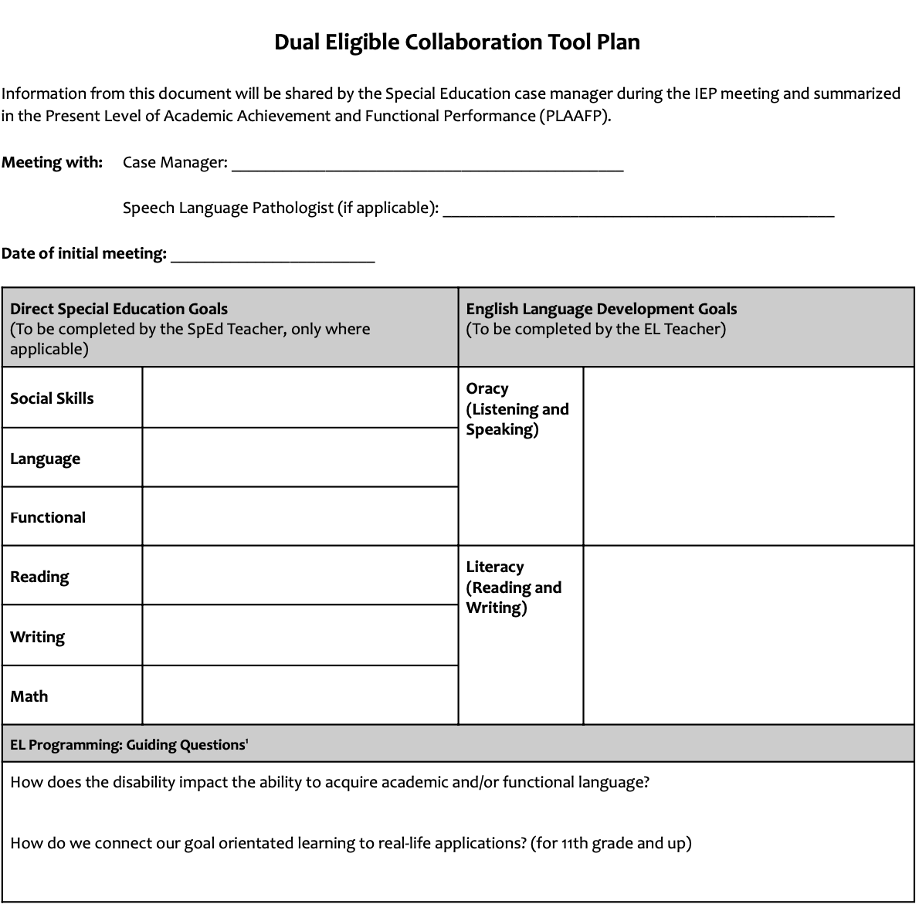

We heard misconceptions such as “I can’t teach language to a student who is nonverbal,” from EL teachers, SpEd teachers, and administration (Huff & Christensen, 2018). There was fear of the unknown regarding different areas of expertise, strategies, acronyms, and legal language. Creating clear roles for each teacher helped to assuage some of this unease; but it was guidance on how to collaborate effectively proved most useful. Critical to this work was the Dual Eligible Collaboration tool (see Figure 3), created in collaboration with other metro districts and the special education and multilingual departments of Minneapolis Public Schools. This graphic organizer supported special education teachers sharing relevant goals with EL teachers who then connected which language features and functions would be useful to develop and support. Paramount is the ongoing discussion of “How does disability impact the ability to acquire academic and/or functional language?” When EL teachers attend IEP meetings and work directly with students, they can give more context to this answer. Each teacher can see the assets they bring via the lens in which they approach their work (Parker & Christensen 2018).

To support EL teachers in creating language learning goals in conjunction with IEP goals, we collaborated with our special education department. Together, we created and facilitated professional development for EL teachers to help them demystify and understand IEP goals. From there, they understood how to use student language strengths and areas of growth to create language learning targets that were in alignment with IEP goals. The activities teachers engaged in were:

- scavenger hunt activities to help teachers familiarize themselves with the IEP;

- collaboratively focusing in on sample IEP goals in order to generate connected language goals; and

- brainstorming activities teachers could use with the students based on these goals.

This process helped to build teacher confidence and inform their instructional planning. Teachers had the steps to create language targets that were now connected to students’ IEPs. We also now had the easy to duplicate to onboarding new teachers.

Shift 3: Quality instruction for ALL

“Ask me as many questions as you can about this picture,” Mr. Wester prompted a student in his co-taught reading class. His professional learning community was focusing on the language of questioning and he was assessing his students utilizing a picture connected to their reading curriculum. When the team chose the focus and reviewed a language trajectory (Multilingual Department, 2022), Mr. Wester immediately started to think of the range of his students and where he would start with each based on their IEP goals. He would prompt a group for WH- questions. In the DCD classroom, he would start by asking questions, testing students on what questions they could respond to using words, signs, or their communication board. He then could utilize this process again and again to assess students on their questioning techniques with new vocabulary and topics, helping to solidify the skill.

In Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning, John Hattie (2012) provides compelling research and useful tools for improving teacher impact on learning. His thesis that learning should be visible is dependent not only on teacher moves but also on the systems created by the school or district to support teacher professional growth and development. In section three of his Visible Learning checklist (Hattie, 2012, p. 28), he notes that the school’s professional development program should:

- enhance teachers’ deeper understandings of their subject(s);

- support learning through analyses of the teachers’ classroom interactions with students;

- help teachers to know how to provide effective feedback;

- attend to students’ affective attributes; and

- develop the teacher’s ability to influence students’ surface and deep learning.

The importance of quality instruction for ALL cannot be emphasized enough when it comes to students who participate in special education, English language development, or in this case, both. Unfortunately, many students do not get to experience the high-impact instruction as demonstrated by Mr. Wester in the vignette above or as stipulated in the Visible Learning checklist.

On July 9, 2002, the President’s Commission on Excellence in Special Education published its report, A New Era: Revitalizing Special Education for Children and their Families, and their findings unfortunately still paint today’s reality. Interviewing and working with a series of diverse focus groups, the commission uncovered nine findings that undermined the intent behind special education services. Most pertinent to our third shift is number 7, which reads: “Children with disabilities require highly qualified, better prepared teachers” (President’s Commission on Special Education, 2002, p. 7). Our teachers also felt unprepared to meet the needs of twice exceptional students.

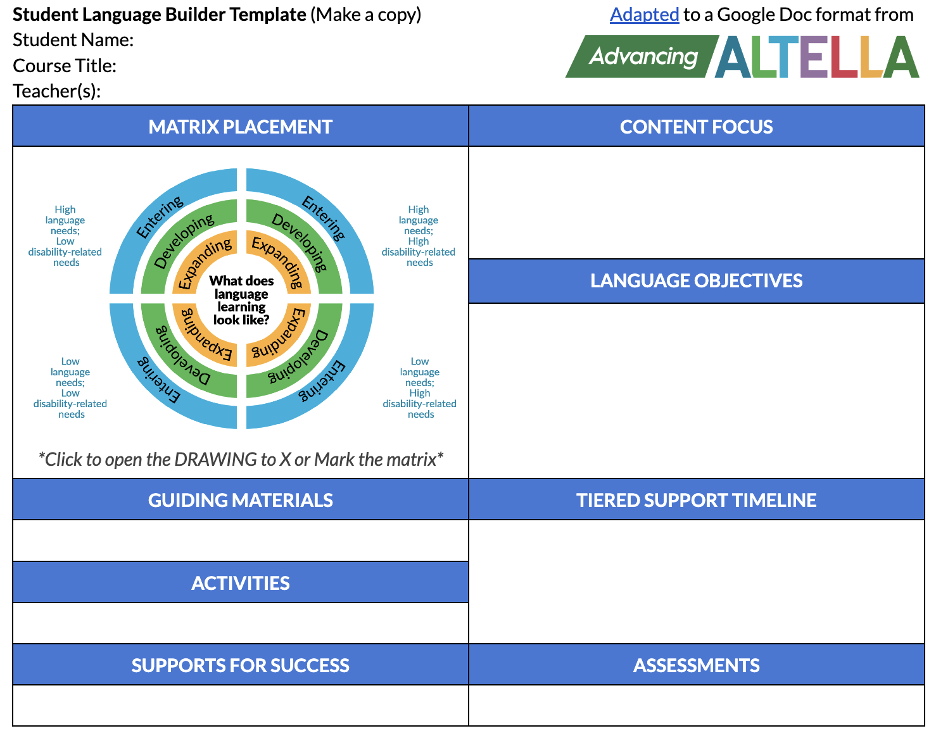

The tide is starting to slowly change. ALTELLA (Alternate English Language Learning Assessment) has been transforming their research and briefs into new resources with their Toolkit (Leech et al., 2022). Grateful for the concrete tool, we worked to create an interactive approach to engaging with the toolkit that embodies qualities of Hattie’s (2012) Visible Learning checklist. By turning the tools into editable Google docs and images, such as the Student Language Builder template (see Figure 4), we created an asynchronous walk-through via a personalized slidedeck that takes EL teachers through the training with a focus on their students. This training has been a successful starting point for teachers like Mr. Wester who serve students with significant cognitive disabilities. With these tools and opportunities for teacher learning, all students can then benefit from high quality instruction.

Conclusion

We share our story in hopes that it will change service models and collaborative practices and improve the quality of instruction for the benefit of twice exceptional students. Our path was five years long and there is much left to do; however, Mr. Wester’s story with his twice exceptional students is federal policy and change in action. Even more important, it is a great example of what is possible to give our students what they deserve.

We close this article with a final vignette:

Returning to the original student from the introduction, Mr. Wester is leading a literacy review lesson identifying common objects and matching text to pictures. Including the new student who is blind and nonverbal, he provides realia, like a ball, and uses both Spanish and English while helping the student manipulate the tool, supporting sign language in English. This is just a typical Friday.

For further reading/resources: https://altella.wceruw.org/resources.html

References

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing the impact on learning. Routledge.

Huff, L., & Christensen, L. (2018). The role of language and communication in the education of English learners with significant cognitive disabilities (ALTELLA Brief No. 7). Retrieved from University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin Center for Education Research, Alternative English Language Learning Assessment project. Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin. https://altella.wceruw.org/pubs/ALTELLA_Brief-07_Language-and-Communication.pdf

Leech, A. M., Shyyan V., & Christensen, L. (2022). Advancing ALTELLA toolkit no. 1: Applying the framework (Advancing ALTELLA Brief No. 2). Retrieved from University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin Center for Education Research, Alternative English Language Learning Assessment project. Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin. https://advancingaltella.org/resource/advancing-altella-toolkit-no-1-applying-the-framework/

Multilingual Department. (2021a). Dual eligible collaboration tool. Minneapolis Public Schools.

Multilingual Department. (2021b). Teacher role chart. Minneapolis Public Schools.

Multilingual Department (2022). ELD instruction and assessment framework. Minneapolis Public Schools.

Parker, C., & Christensen L. (2018). Individualized education programs for English learners with significant cognitive disabilities (ALTELLA Brief No. 4). Retrieved from University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin Center for Education Research, Alternative English Language Learning Assessment project. Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin. https://altella.wceruw.org/pubs/ALTELLA_Brief-04_IEPs.pdf.

President’s Commission on Excellence in Special Education, (2002, July), A new era: revitalizing special education for children and their families. Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Washington, DC.

Shyyan V., Gholson, M., & Christensen, L. (2018). Considerations for educators serving English learners with significant cognitive disabilities (ALTELLA Brief No. 2). Retrieved from University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin Center for Education Research, Alternative English Language Learning Assessment project. Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin. https://altella.wceruw.org/pubs/ALTELLA_Brief%2002_Considerations.pdf.

U.S. Department of Education. (2014, July). Questions and answers regarding inclusion of English learners with disabilities in English language proficiency assessments and Title III annual measurable achievement objectives. https://sites.ed.gov/idea/idea-files/qa-regarding-inclusion-of-english-learners-with-disabilities-in-english-language-proficiency-assessments-and-title-iii-annual-measurable-achievement-objectives/

U.S. Department of Education & U.S. Department of Justice. (2015, January). Dear colleague letter: English learner students and limited English proficient parents. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-el-201501.pdf