“Be Your Dream” academic coaching is a research-based approach to helping students develop a growth mind-set, set and achieve personal and academic goals, and create an identity as confident, self-directed learners. This article presents a case study of academic coaching in a sixth-grade ESL setting.

Middle School ESL: What are the challenges?

During the 2014-2015 school year, I taught sixth grade ESL in an urban setting at a school that serves approximately 750 students from preschool – grade 8. Fifty-nine percent of the students were English Language Learners, mostly from East Africa; ninety-three percent of students received free or reduced-price lunch.

My students crossed multiple cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic borders every day. They were constantly navigating a complex set of challenges and thresholds. In addition, they were emerging adolescents in a country and culture that was unfamiliar to them to varying degrees. Students might have been more likely to struggle personally or socially if they also had a history of trauma (Halcón, Robertson, Savik, Johnson, Spring, Butcher, Westermeyer & Jaranson, 2004). And regardless of how recently they had immigrated, very few had a sufficient command of academic English to provide them with success at school.

Having previously worked with high school and college students, adapting my practice to serve emerging adolescents was a challenge. As recognized in a 2002 position paper on how to best support students in their transition to middle school, adopted by both the National Middle School Association and the National Association of Elementary School Principals, sixth grade in particular is a very challenging time academically for many students, as they enter secondary school and must meet more rigorous expectations with less support than in elementary school (Association for Middle Level Education [AMLE]). Many of my students found this transition to be very difficult, and I wasn’t sure how best to help them. They needed just the right balance of structure and routine, along with autonomy and opportunities to explore and develop their own identities as young people and as scholars, supported by positive relationships with peers and adults (Wentzel, 1998).

Digging Deeper: What’s going on here, and what can we do about it?

In an effort to learn more about my students’ feelings about school and their experiences, I administered a short survey to the sixth-graders in my co-taught science classes. The survey included questions similar to those on the Minnesota Student Survey (Minnesota Department of Education [MDE], Minnesota Department of Health, Minnesota Department of Human Services, and Minnesota Department of Public Safety, 2013) about relationships with adults and peers at school and students’ perceptions of safety.

One question asked which adults students felt they could approach with problems at school. I was saddened but not surprised to see that more than ten percent of sixth graders did not feel a strong connection to any adults at our school. That single fact told me a great deal about students’ experiences in school and their sense of belonging. It helped to explain why students might not feel connected to their classes or might struggle academically. If they don’t feel connected or supported by adults, their buy-in to an academic system may be negatively affected. These findings matched trends observed on the Minnesota Student Survey, which found that while increasing numbers students have reported feeling that their teachers care about them since 2001, in 2013 “less than half of the students felt that their teachers cared very much or quite a bit” (MDE, et al., 2013, p. 8).

In many one-to-one conversations with students, it became clear that along with an absence of supportive relationships, fear of “looking stupid” was at the root of many challenges that students faced. In our conversations, many young people expressed deep, underlying fear about their academic ability. I wondered how best to help students develop more confidence.

It was at this time that I learned about a program called Be Your Dream Academic Coaching. The program was developed and taught by Nancy Hellander Pung, CEO of Design From Within Coaching and adjunct faculty at Hamline University. Be Your Dream is a comprehensive approach to academic coaching based on the International Coach Federation’s Core Coaching Competencies (“Core Competencies,” n.d.), as well as current research in neuroscience and educational psychology.

It seemed like exactly the resource my students and I needed: a structure and framework for conversations that could help me build relationships with my students, provide them with a safe and supportive space, and encourage them to embrace their own potential and develop a greater sense of agency and capacity as young scholars. I signed up for the course immediately, eager to learn and build my own skills and thereby better serve the many students in my classroom.

Research Review: We’re not alone.

The struggles and concerns that my students and I identified in the classroom make a great deal of sense in the context of broader educational research. It is well established that a sense of belonging and connection is important for student academic motivation and achievement for middle school students, especially in sixth and seventh grade (Goodenow 1993, Wentzel 1998, AMLE 2002). This might be called a “belonging mindset” (Rattan, Savani, Chugh & Dweck 2015).

In addition to the importance of belonging to a community and positive relationships in supporting students’ academic success, it is also clear that students’ core beliefs about their own ability also have a great deal to do with their success in school and their ability to rebound from setbacks. As Carol Dweck (2010) has amply documented, students with a “growth mind-set” outperform students with a “fixed mind-set” (p. 26). Dweck’s research also demonstrates that a growth mind-set can be taught to students, and that changing their mind-sets can help to motivate them to succeed. This research is essential not just for individual students, but in order to ensure more equitable educational opportunities to all students: “Teaching a growth mind-set seems to decrease or even close achievement gaps” (2010, p. 28).

Given the vast challenges that many students face simply because of their socioeconomic and linguistic backgrounds – in a society that often sees their backgrounds as deficits – creating a safe environment for risk-taking that includes building strong, supportive relationship and teaching a growth mind-set seems to be not just a positive idea but an imperative.

The Framework: What is “Be Your Dream” academic coaching?

In the Be Your Dream course, I learned about the UP coaching framework. UP is an acronym for Unlimited Potential; instructor Nancy Hellander Pung emphasizes the importance of beginning with the assumption that our students’ potential to learn and achieve is unlimited.

Beginning with the assumption of unlimited potential sets a positive, affirming tone for interactions with students. Challenging fixed mind-sets about ability and intelligence allows space to develop a growth mind-set, with belief in the potential and possibility inherent in every child. Communicating that belief and confidence in the possibility of growth and change is a key part of the academic coaching framework and it is one of the most important strategies I learned from this course.

Other strategies taught in the course included a coaching framework that begins with asking students to identify their big dreams and goals for their lives. Identifying dreams and goals opens space for a conversation about students’ underlying values, which is a powerful tool for building student confidence and reinforcing a positive and affirming sense of identity.

Once students identify their dreams, goals, and core values, the coaching framework helps students walk through the steps they’ll need to take to reach their goals, identifying specific and actionable steps, and brainstorming ways to overcome potential barriers. The framework is always focused on empowering students to create their own plans and build accountability systems, with support from the coach. The coach also helps students identify their thoughts and beliefs, which lead to actions and ultimately results. A powerful aspect of the coaching framework is helping students to find ways to consciously adjust their thoughts, beliefs, and actions in order to achieve the results they long to see in their lives (Hellander Pung 2014).

Framework To Practice: How does it work in real life?

I chose to formally practice academic coaching with one young person. A. was typical of many of my students. She arrived in late September 2014 with a WIDA score of 2.3. Within her first several weeks, she received a disciplinary referral for verbal fighting with other students. Her fall MAP reading score was 174, far below a passing score of 203, which would indicate grade-level proficiency in reading. Her first semester GPA was 2.5, with a D- in math.

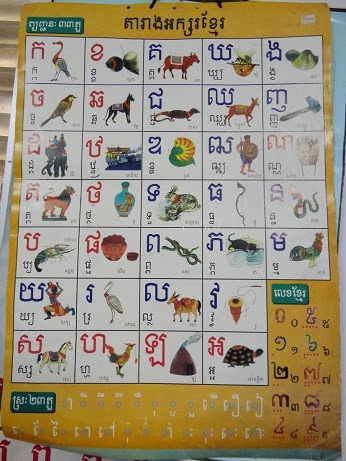

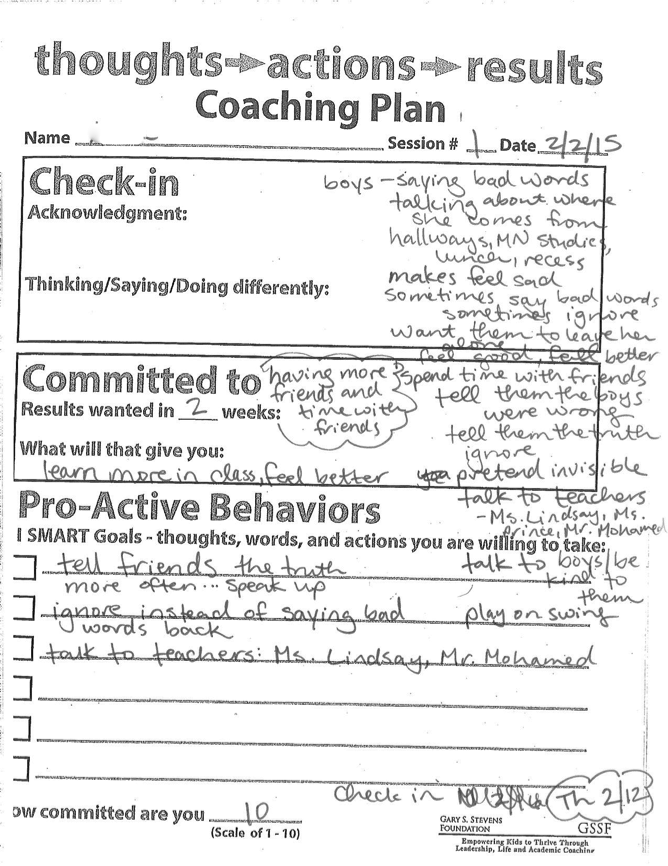

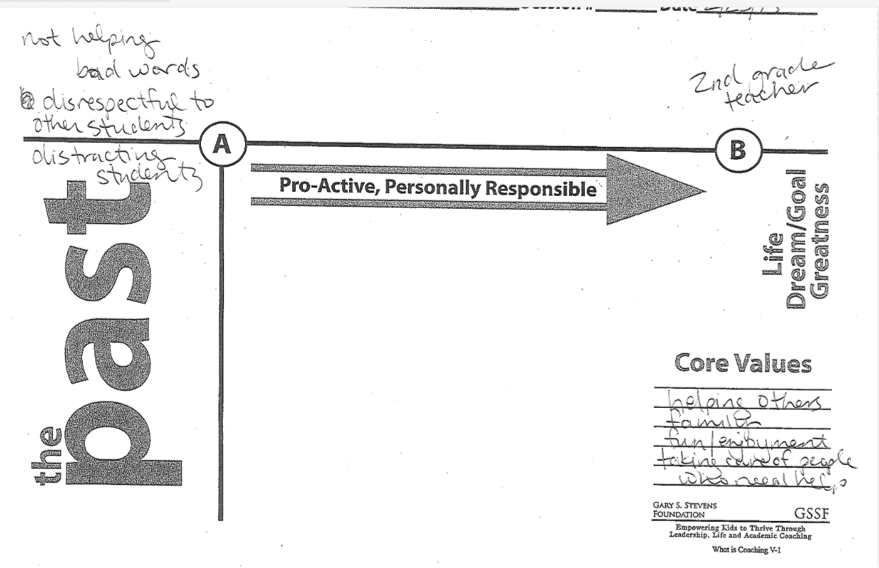

In our first coaching session, I began by introducing the coaching process and goals, and asked for A.’s permission to coach her. We talked about her goals and dreams for herself, and identified obstacles and challenges to meeting those goals. She then created a set of action steps she could take to begin to meet her goals. I used coaching forms created by Nancy Hellander Pung to guide and document our conversations, shown here in Figure 1, used with permission.

In this first session, it is clear that A. was most concerned about her social interactions with other students. She was struggling to form friendships with other students, and several students were bullying her. She said this made her feel sad, and sometimes she said bad words back to them, which made her feel worse. Her only other strategy was to “pretend to be invisible,” which also made her feel sad and lonely.

The goal that A. created in this first session was to have more friends and more time with her friends. Her motivation for meeting this goal was to feel better and to learn more in class, rather than being distracted by bullying. The steps to reach this goal that she identified included telling teachers when bullying was happening, speaking up and being honest with the girls who were her friends rather than pretending to be invisible, and working hard to ignore mean comments rather than responding aggressively herself. On a scale from one to ten, she rated her commitment to this plan at a ten, and we agreed to check in about a week and a half later.

Making Progress: Opening Up to the Big Picture

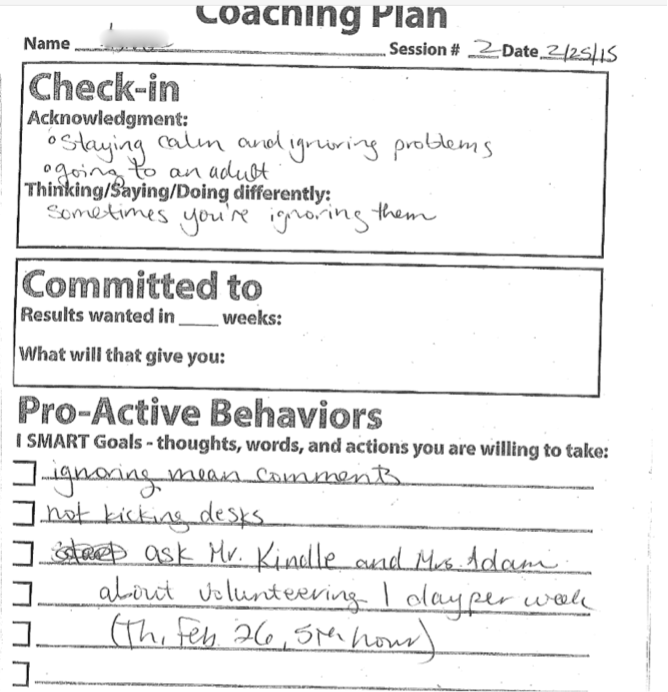

In our second session, which is documented in Figure 2, I began by acknowledging the progress that A. had made toward her goal.(Click on the image to make it bigger.) She was focusing on ignoring negative comments and going to an adult rather than taking matters into her own hands when she had conflicts with students. Using those strategies was helping her to stay calm and have fewer negative interactions with others. In reflecting on how her own thoughts and actions had changed, A. recognized that although it continued to be challenging, sometimes she was successfully ignoring students who bothered her.

We then talked about A.’s “big dream” for her life, using the template shown in figure 3. (Click on the image to make it bigger.) It was in this conversation that I learned about A.’s dream of becoming a second-grade teacher. She talked about playing school and teaching her younger siblings at home, and how much she enjoyed working with children and helping them learn. This moment felt like a break-through. We opened up beyond the immediate issues facing her in sixth grade, and started to find ways to identify her core values and connect her daily actions to the bigger dream she had for her own life.

This was a powerful conversation because it helped both A. and me to understand more about her underlying values and goals, and helped both of us to find more connections between her day-to-day life at school and her own big dream for her future. This allowed her to have a different perspective on her social and academic experiences. Our initial conversation had been very narrow in scope: She was upset about bullying and felt that she had very few strategies to address it. When she had a few immediate strategies to address it in the moment – talking to an adult and doing her best to ignore rather than retaliate – she was able to take a step back and find more long-term strategies that were connected to more of her whole self, grounded in her own values and dreams.

Noticing the Change: How do we recognize growth?

In our third formal session, A. and I had a completely different conversation than the first time we talked. It had been about eight weeks, and in contrast to our first talk about bullying, wanting friends, and pretending to be invisible, during this coaching session A. focused on her volunteering in a fifth-grade classroom, how she felt she was building skills that would help her be a teacher one day, and how she was becoming more responsible and serving as a role model for others. When she set her goals, she focused on paying attention in class, completing work, and checking her grades. This shift toward an academic focus indicated to me that many of the steps she was taking were helping her to find her place and sense of belonging, which then allowed her to focus more on learning and scholarship in the classroom. This positive shift continued throughout the spring.

There were several other indicators of the ways her engagement with school changed. Her Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) reading score increased eight points from 174 to 182, still below grade level but indicating growth. Her WIDA English proficiency score increased from 2.3 to 3.8, a huge amount of growth in her academic language skills. She had no more disciplinary referrals, and her grade point average increased from 2.5 to 2.875, with a B- in math.

Practice into Praxis: What has changed for me?

It was inspiring and affirming to confirm the improvement in A.’s grades and test scores, as well as to see the ways that her self-confidence and belief in her own self-efficacy changed throughout the coaching process. As an educator, my goal is always to ensure that my instruction is relevant, engaging, and meaningful to students. There were many ways in which I was already working to meet that goal, and the UP coaching framework has given me more tools to do that.

Based on what I learned throughout this experience, I will strive to always be conscious of the dreams and goals that students have for themselves. I will look for the deeper intention behind students’ goals and desires and listen for their core values. I will focus check-in conversations on concrete, actionable steps that help students get measurably closer to their goals, check their level of commitment, and help them to build networks of support and accountability.

Finally, I’m reminded that our students are brilliant young people who are the experts on their own experience and who very often know exactly what they need. They have dreams and goals; they need adults to support and nurture them, but they don’t need adults to define them. My goal as a teacher and coach is to create spaces where students can “step into their big dreams,” in the words of Nancy Hellander Pung (2014), and to “hear students into speech,” in the words of Parker Palmer (2007). The insights I’ve gleaned from this course have further strengthened my belief in the capacity and unlimited potential of all young adults, and deepened my appreciation for the opportunities I have to share the journey with them however I can.

References

Association for Middle Level Education. (2002). Supporting students in their transition to middle school. Retrieved from http://www.nppsd.org/vimages/shared/vnews/stories/-525d81ba96ee9/Tr%20%20Supporting%20Students%20in%20Their%20Transition%20to%20Middle%20School.pdf.

Core competencies. (n.d.) In International Coaching Federation. Retrieved from https://www.coachfederation.org/credential/landing.cfmItemNumber=2206&navItemNumber=576.

Cummins, J. (2001). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: California Association for Bilingual Education.

Dweck, C. (2010). Mind-sets and equitable education. Principal Leadership, 10(5), 26-29.

Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79-90.

Halcón, L., Robertson, C., Savik, K., Johnson, D., Spring, M., Butcher, J., Westermeyer, J., & Jaranson, J. (2004). Trauma and coping in Somali and Oromo refugee youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(1), 17-25.

Hellander Pung, N. (2014). Be your dream: leadership and academic coaching skills (presentation slides). Presented in MPS ProPay Course #90691, Winter 2014.

Minnesota Department of Education, Minnesota Department of Health, Minnesota Department of Human Services, and Minnesota Department of Public Safety. (2013). Minnesota student survey 1992-2013 trends.

Palmer, P. J. (2007). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Rattan, A., Savani, K., Chugh, D., and Dweck. C. (2015). Leveraging mindsets to promote academic achievement: Policy recommendations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(6), 721-726.

Snyder, C. R. (Ed); Lopez, Shane J. (Ed), (2002). Handbook of positive psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Wentzel, K. (1998). Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(2), 202-209.