An adult ESL teacher recounts her frustrating experience of returning to the language classroom in the role of a beginning level learner and outlines four teaching practices that can support struggling adult language learners.

Dear students,

I told you many, many times that I understood how difficult it was to learn a new language that was completely different from your first language. I told you that I understood what you were going through and how much you were struggling. I told you that I empathized with your frustration at learning a new alphabet and language system, and that I knew where you were coming from when you teared up during class or called yourself stupid or slow. And I meant every word. I really thought that I understood your experience. I was so very, very, wrong. I had no idea. This. Is. So. Hard.

Sincerely,

Teacher Andrea

(From my personal blog post, “An Open Apology to All My Former Learners” written on November 16, 2013)

In high school and my first year of college I had muddled my way through Spanish classes, emerging with the ability to discuss food, the weather, and my family in fairly rudimentary terms. I dreaded conjugating verbs and despised the subjunctive tense, and my grasp of syntax was appalling, to say the least. Yet despite my mediocre language learning skills, I somehow found myself in front of an adult ESL classroom in the role of a teacher, and fell completely in love with the work and the learners. Working with literacy-level adult immigrants and refugees was far and away my favorite class to teach. It was us against the English language, and I was sure that I understood their struggles.

I always joked that the fact that I was a poor language learner was what made me a strong teacher. When I would teach new skills or concepts, I would ask myself, “what would it take for me to learn this?” While this approach certainly served my learners well in some cases, I didn’t truly realize the depths of some of their struggles. In particular, I wasn’t able to relate to the challenges and frustrations faced by adult learners learning to read and write for the first time in their lives, or learning to read and write in a brand-new alphabet, while functioning in a high-stakes setting. It would take putting myself back into the role of a language student, sitting on the other side of the desk and feeling completely lost and overwhelmed, to cause me to reexamine my long held beliefs about effective classroom instruction for literacy level learners.

In 2013, I had the opportunity to join the English Language Fellow program, which is run by the US State Department and places ESL professionals in capacity-building English Education projects at language universities around the world. My husband and I packed up our lives and moved to our new home for the next two years: Phnom Penh, Cambodia. One of the first things that I did once we were settled into our new home was to sign us both up for a Khmer (the official language of Cambodia) as a Foreign Language class at the Institute of Foreign Languages, where I was serving my fellowship.

I looked forward to an exciting experience of learning to listen, speak, read, and write in Khmer, which has a writing system originally derived from Brahmi, an ancient Indian script. I anticipated that it would be a steep challenge, but that my past five years of working with literacy level adult learners would serve me well, and that I would be able to bring all of the strategies that I’d developed as a teacher into my new role as a learner. I was confident that I would emerge a stronger literacy-level teacher, and despite my previous poor learning experiences, I was sure that once I started learning a language that I was invested in learning while being immersed in the culture, I would pick it up quickly.

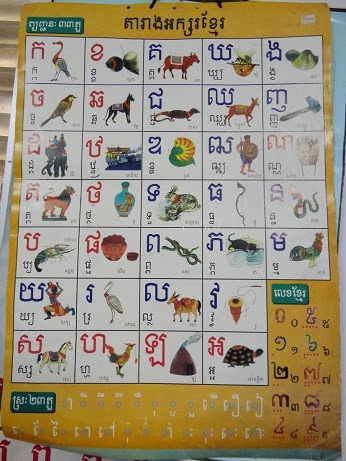

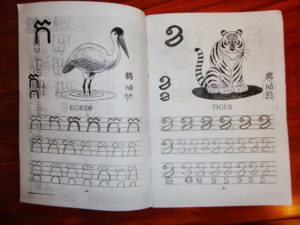

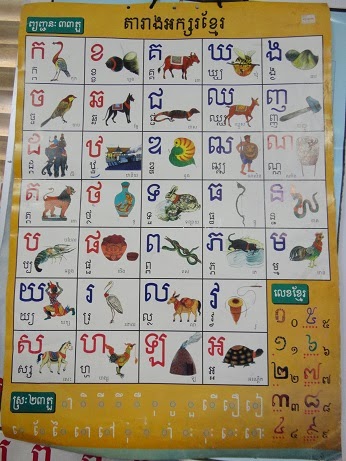

Ten minutes into the first day of class and all of my self-confidence had evaporated. The Khmer alphabet  appeared to be an indecipherable combination of circles and squiggles, and for the first time I could remember, I wasn’t literate. The class structure and expectations were completely foreign to me. Sitting in the class was like stepping back in time 50 years; the teacher, a sweet elderly man in his 70s, ran classes the same way every night. The teacher wrote on the board, we copied it down in our notebooks. He read aloud, we repeated after him. We would do an exercise in our workbooks, then one-by-one, every student would read the exercise aloud while the teacher sat in front of the room, prompting and correcting pronunciation. He always started with the student on the right-hand side of the front row, and then worked his way back. The first week my husband and I sat in the front row. By the second week I’d moved us back a row to give me more time to prepare before I was called upon to read. By the third week I was trying to get to class early so that we could get a seat in the coveted back row.

appeared to be an indecipherable combination of circles and squiggles, and for the first time I could remember, I wasn’t literate. The class structure and expectations were completely foreign to me. Sitting in the class was like stepping back in time 50 years; the teacher, a sweet elderly man in his 70s, ran classes the same way every night. The teacher wrote on the board, we copied it down in our notebooks. He read aloud, we repeated after him. We would do an exercise in our workbooks, then one-by-one, every student would read the exercise aloud while the teacher sat in front of the room, prompting and correcting pronunciation. He always started with the student on the right-hand side of the front row, and then worked his way back. The first week my husband and I sat in the front row. By the second week I’d moved us back a row to give me more time to prepare before I was called upon to read. By the third week I was trying to get to class early so that we could get a seat in the coveted back row.

Even after a couple months of class, copying letters and words of the Khmer alphabet felt as though I were drawing bizarre pictures, rather than writing. My hands would cramp up from how tightly I would hold the pencil and I would have to take breaks and shake them out. The letters blurred together; just when I thought that I had one consonant mastered, the font in the book would change and I’d be completely lost again. And don’t even get me started on the Khmer vowel system. A simple homework task took forever, and, because of my unfamiliarity with the alphabet, felt like pointless copying. Outside of the classroom, I struggled to identify individual letters on street signs and shop awnings. Sounding words out was a long, laborious process, and often once I’d sounded a word out, I’d realize that I had no idea what it meant due to my small vocabulary.

pencil and I would have to take breaks and shake them out. The letters blurred together; just when I thought that I had one consonant mastered, the font in the book would change and I’d be completely lost again. And don’t even get me started on the Khmer vowel system. A simple homework task took forever, and, because of my unfamiliarity with the alphabet, felt like pointless copying. Outside of the classroom, I struggled to identify individual letters on street signs and shop awnings. Sounding words out was a long, laborious process, and often once I’d sounded a word out, I’d realize that I had no idea what it meant due to my small vocabulary.

By three months into the class, my fellowship work was piling up and I decided that I couldn’t stand to subject myself to the stress of language classes anymore. After a full day of teaching and lesson planning, while negotiating a brand-new culture and academic system, all I wanted to do was go back to our apartment and collapse in the evenings. I quietly dropped the class and vowed to try and avoid my former teacher around campus at all costs. I found a tutor whom I met with at a coffee shop once a week, and we focused exclusively on spoken Khmer that I would be able to use in daily interactions.

When I returned to the United States and stepped back into a literacy-level classroom, I had ample opportunity to reflect on the lessons that could be gleaned from my frustrating language learning experience. Now that I’d had the opportunity to see the classroom from the point of view of a struggling learner, what teaching principles could I identify that might have helped me to be more successful in my language learning? What could I take away from my language learning experience that would help me to become a stronger and more responsive teacher? Some of my beliefs were challenged, and some were confirmed, but the experience certainly impacted how I approach teaching.

Described below are four teaching practices that, based on my personal experiences, will now always be central tenets of my classroom instruction. While these four practices have been proven through research to be effective in meeting the instructional and classroom needs of literacy-level adult learners, they could also, as my experience proved, benefit adult learners who are highly literate in their native language, yet struggling in their second language classroom.

Teacher, my brain is no good!

Lowering the affective filter is critical. Many teachers, myself included, who have worked with low-literacy adult classes have often heard their learners disparage their own learning abilities. It’s also not uncommon to have learners tear up during activities, become so overwhelmed that they stop even trying to participate, or exhibit signs of extreme frustration with themselves in the language classroom. This negative perception of personal capability, in particular when it comes to learning a new language, is not unique to learners who have had limited educational experiences, who have suffered trauma, or who have a specific set of personality characteristics.

In Cambodia, I was initially confident in my ability to learn and highly motivated, but my positive attitude quickly morphed into feelings of failure and questioning my own intelligence when I didn’t have any opportunities to experience success. The class moved too quickly for me; the teacher introduced between 5-10 alphabet symbols a night, with very little opportunities for repetition. After a month the workbook had moved into phrases and sentences while I was still struggling to identify the letters. Reading out loud in front of the class was particularly painful; the teacher would correct every little pronunciation mistake that I made until I wanted to sink through the floor with embarrassment. I was taken aback at how frustrated I would become at myself when I struggled in my Khmer class, and how quickly I began to have physical symptoms of anxiety during class, sometimes even before it would begin.

Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA) is a documented and researched phenomenon. It’s described as starting as a negative affective response to some experience in language class that, with repeated experiences, develops into an anxiety reliably associated with the language class (Dewaele, Petrides, & Furnham, 2008). A learner who is extroverted, confident and highly motivated may become introverted, anxious, and unmotivated. There is a clear path between FLA and motivation; while high levels of motivation can suppress anxiety, high levels of anxiety can suppress motivation (Gardner & MacIntyre, 1993). It is of the utmost importance that teachers provide their learners with opportunities to experience success with the target language; simply telling them that they are doing a good job is not sufficient. According to MacIntyre, “aptitude can influence anxiety, anxiety can influence performance, and performance can influence anxiety” (1995, p. 95).

Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA) is a documented and researched phenomenon. It’s described as starting as a negative affective response to some experience in language class that, with repeated experiences, develops into an anxiety reliably associated with the language class (Dewaele, Petrides, & Furnham, 2008). A learner who is extroverted, confident and highly motivated may become introverted, anxious, and unmotivated. There is a clear path between FLA and motivation; while high levels of motivation can suppress anxiety, high levels of anxiety can suppress motivation (Gardner & MacIntyre, 1993). It is of the utmost importance that teachers provide their learners with opportunities to experience success with the target language; simply telling them that they are doing a good job is not sufficient. According to MacIntyre, “aptitude can influence anxiety, anxiety can influence performance, and performance can influence anxiety” (1995, p. 95).

While this in no way means that teachers must ensure that learners never have a negative experience in their English class, adhering to best practices such as scaffolding language activities, repetition of content and language, and providing opportunities for preparation and rehearsal can alleviate anxiety as well as promote confidence and motivation. Additionally, teachers can help to improve their learners’ self-perception of proficiency through focusing on learners’ successes and positive experiences with the language (Chen & Chang, 2004). Often learners have difficulty recognizing their own growth; they get caught up in their daily struggles and fixated on their mistakes. Teachers can help their learners to remain motivated through providing them with concrete examples of the progress that they are making.

What does this have to do with me?

Connecting instruction to learners’ lives. In the English classes that I taught, I generally attempted to connect the content of the instruction with the lives of my learners. My learners and I wrote stories about immigrant families dealing with unresponsive landlords, we read notices from their children’s schools, and had conversations about their lives and experiences outside of the classroom. But like most teachers, I would sometimes find myself working with lists of word families that were filled with unfamiliar vocabulary, or would run short of prep time and use a picture story about a penguin wearing a backpack and walking to the market to buy fish.

While a busy teacher who used pre-prepared curriculum is by no means a bad teacher, it’s important to realize how frustrating it can be to be asked to learn words and vocabulary that you cannot use outside of the classroom. I very clearly remember sitting in Khmer class and staring down at a page in my class workbook that had us copying out the words for “playing cards” and “bowtie”, which both started with the same Khmer consonant. I did not want to learn those words. I did not need these words. I did not want these words taking up space in my head. I needed that space for important words like “help” and “how much” and “please speak slowly”.

In their 2006 article entitled ““What works” for adult literacy students of English as a second language”, Condelli and Wrigley discuss the importance of “bringing in the outside,” or in other words, connecting the content of the class to issues that the learners care about in their lives outside of the classroom. Vinogradov and Bigelow (2010) also emphasize the value of connecting instruction to learners’ lives when working with low-literate adult learners, and offer several recommendations for developing learner-generated texts, such as the Language Experience Approach (LEA) where learners share a common experience and then tell their story while the teacher transcribes what is said, or writing about a picture or a drawing, using dialogue journals, or writing down cultural stories or jokes. Whichever method is used, the power of this approach lies in the fact that the learners will have a personal stake in the language being taught in class, and will have a much greater chance of being invested in learning. As an added benefit, learners will also have a much greater likelihood of using the language being taught in class outside in the community, which will increase their perception of the value of their English class.

Different strokes for different folks.

Multi-level instruction and variety in modalities and activities. Most ESL teachers will agree that there is no such thing as a homogeneous classroom. In my years of teaching ESL, I never once have taught a class that didn’t contain a wide range of language abilities and learning styles. It was not uncommon for my classroom to have learners who had attended post-secondary education sitting next to learners who were learning to read for the first time in their lives. Also, even when learners enter the class at the same language level and with similar educational backgrounds, there are a number of factors such as aptitude, learning style preferences, and investment in learning that can cause wide deviations in developing their target language proficiency.

In Cambodia, my husband and I had completely opposite language learning experiences. While I agonized and struggled in Khmer class, my husband excelled. He has a natural ability to mimic accents and sounds, an excellent aural memory, and he found learning the Khmer alphabet to be just like the code-breaking games he loved as a child. Not surprisingly, this sharp discrepancy between our abilities was an endless source of frustration for me. I would have gladly welcomed the opportunity to work on activities at my level that matched my kinesthetic-tactile learning preferences, since attempting to keep up with the class’s rapid speed and lecture teaching style was simply not working. Additionally, having the chance to interact and practice with other Khmer-language learners who were also struggling with the language would have curbed my continuous comparisons between my husband’s progress and my own.

One of the key tenets to successful multi-level instruction, particularly at the literacy level, is providing varied practice and language interaction opportunities to ensure that all learners are able to practice and learn in a way that is accessible to them (Condelli & Wrigley, 2006; Vinogradov & Bigelow, 2010). A similar classroom approach is multisensory structured language instruction, which is recommended for at-risk foreign language learners (learners with difficulties or anxiety). This type of explicit and systematic learning of the language includes instruction through all of the modalities (visual, auditory, and kinesthetic-tactile). The resulting slowed down pace of the class and use of scaffolding, varied practice opportunities, and repetition is suited to literacy level learners, and reduces learning anxiety (Chen & Chang, 2004).

While it can be tempting for us teachers to keep the class moving ahead at the speed of the fastest and brightest learners, we have a responsibility to provide achievable tasks and targeted instruction for the lowest learners as well. Multi-leveled activities that incorporate the three modalities are essential. In classroom instruction, this may include small group work with appropriately leveled objectives, learning stations, volunteer-led pull-out sessions, and, above all, practice and repetition.

Is that even a word?

Developing vocabulary and oral skills. Thanks to standardized assessment requirements in ABE, a vast majority of which measure only reading and writing skills, there is always a great deal of pressure for teachers to focus a majority of their classroom lessons on print literacy. While the importance of print literacy cannot be overstated, the modalities of speaking and listening should not take a back seat, especially in a literacy-level classroom. Decoding words in my Khmer class often felt like a pointless and unproductive exercise since I was very rarely familiar with the vocabulary in the workbook. There was no opportunity for me to self-assess or receive the immediate feedback that occurs when a familiar word is successfully sounded out. What I was desperately in need of when I first moved to Cambodia were oral conversation skills so that I could shop for food in the markets, secure transportation around the city, start to make connections with people in my new community, and advocate for myself as a newcomer to the country.

The research tells us that for literacy-level ESL learners, emphasizing oral communication skills and vocabulary development helps them to develop a personal resource that they are able to draw on as they become literate. This can have a strong positive impact on the progression of literacy skills (Condelli & Wrigley, 2006; Kurvers, 2007; Vinogradov & Bigelow, 2010). The consequences of attempting to delve into literacy without first strengthening oral skills is stated perfectly by Kurvers (2007), who says “[without] vocabulary development in the second language, reading is like sounding out nonsense words” (p. 41). Teachers must give prominence to the development of a vocabulary bank and spoken language, to prepare learners to have success with learning the decoding techniques required in order to read. Literacy level classrooms should be places where learners aren’t afraid to open their mouths and make noise as they find their voices and begin to negotiate meaning and make sense of English.

Final reflections

Going back into the language classroom and experiencing language learning from the other side of the desk was an eye-opening experience. Particularly as a teacher, it was humbling to struggle at something that I wanted to excel at, and disheartening to feel that I was making no headway in my language skills. And most powerful of all, it was staggering to realize just how little I’d actually been able to grasp the discomfiture that many of my learners faced every day in their English classes. I had the luxury of being able to choose to leave my Khmer class and find a learning situation better fitted to my needs; my learners have to keep coming back, every day, no matter how frustrated they feel. I will try my upmost to apply the lessons that I learned to my classroom practice as I move forward as a teacher and a trainer. I will do my best to always remember: This. Is. So. Hard.

References

Chen, T., & Chang, G. (2004). The relationship between foreign language anxiety and learning difficulties. Foreign Language Annals 37(2), 279-289.

Condelli, L., & Wrigley, H. S. (2006). Instruction, language, and literacy: What works study for adult ESL literacy students. In I. van de Craats, J. Kurvers, & M. Young-Scholten (Eds.), Low-educated adult second language and literacy acquisition: Proceedings of the inaugural symposium (pp. 111-133). Utrecht, The Netherlands: LOT.

Dewaele, Jean-Marc and Petrides, K.V. and Furnham, A. (2008). The effects of trait emotional intelligence and sociobiographical variables on communicative anxiety and foreign language anxiety among adult multilinguals: A review and empirical investigation. Language Learning 58(4), 911-960.

Gardner, R. C., & MacIntyre (1993). On the measurement of affective variables in second language learning. Language Learning, 43, 157-194.

Kurvers, J. (2007). Development of word recognition skills of adult L2 beginning readers. In N. R. Faux (Ed.), Low-educated adult second language and literacy acquisition proceedings of symposium (pp. 23-44). Richmond, VA: Literacy Institute at Virginia Commonwealth University.

MacIntyre, P. D. (1995). How does anxiety affect second language learning? A reply to Sparks and Ganschow. The Modern Language Journal, 79, 90-99.

Vinogradov, P., & Bigelow, M. (2010). Using oral language skills to build on the emerging literacy of adult English learners. Retrieved February 19, 2012 from http://www.cal.org/caelanetwork/resources/using-oral-language-skills.html