Angela Froemming & Emily Mattson

ESL teachers can leverage their expertise to bridge the Science of Reading and a genre-based approach to writing, supporting multilingual learners in developing language and literacy skills that empower them to read and write effectively across contexts.

Keywords: elementary, literacy, writing, science of reading

Introduction

This article explores the relationship between the Science of Reading (SoR) and genre-based writing instruction. Reading instruction, specifically the SoR, is the focus in many schools right now. As of September 2024, 40 states and the District of Columbia had passed laws or policies mandating evidence-based reading instruction grounded in the SoR (National Education Association, 2024). Given this current emphasis on the SoR, English as a second language (ESL) teachers may feel pressured or expected to align their work directly with reading instruction. Extant literature shows that ESL teachers have historically been pulled in many directions, often in the direction of being an additional reading teacher (Froemming, 2023; Harper et al., 2008; Liggett, 2010).

While we wholeheartedly acknowledge the value of reading instruction, we argue that ESL teachers should not be relegated to additional reading instruction roles. Instead, they can leverage their expertise in language to integrate SoR-aligned principles into writing instruction through a genre-based approach, ultimately supporting multilingual learners in developing both literacy skills and academic language proficiency. Our experience and research show that language instruction and the SoR complement each other. For example, many of the practices promoted within the SoR connect to language development and include concepts such as building oral language, teaching vocabulary, and maximizing student engagement (Moats & Tolman, 2019).

This article highlights three principles that are promoted in both the SoR and a genre-based approach to writing—using a systematic approach to literacy development, building background knowledge, and providing explicit instruction. We believe these are essential practices in which ESL teachers have expertise, positioning them to connect these two approaches to effectively support multilingual learners in developing strong literacy and language skills.

What is the science of reading?

The Science of Reading is an interdisciplinary body of research that examines how people learn to read and identifies the most effective instructional methods (Moats & Tolman, 2019). It emphasizes the importance of systematic, explicit instruction in essential word recognition components such as phonemic awareness, phonics, and sight word identification, while also recognizing the critical role of linguistic comprehension components of vocabulary, background knowledge, language structures, and verbal reasoning (Scarborough et al., 2001).

This connection of word recognition and language comprehension is known as The Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986) and is a foundational framework in this field. Their framework stresses the idea that proficient reading comprehension emerges from the integration of effective decoding skills and strong linguistic comprehension. Grounded in evidence from cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and education, the SoR approach demonstrates that a balanced focus on both decoding and language understanding is essential for reading success (Dehaene, 2013; Ehri, 2014; Gough, 1972; Seidenberg & McClelland, 1989). While the SoR provides a strong foundation for reading development, writing instruction requires additional scaffolds to help students produce different types of texts. This is where a genre-based approach can be particularly useful, providing a structured way to deliver explicit instruction in language and writing.

What is a genre-based approach to writing?

A genre-based approach to writing, also called genre-based pedagogy, is a structured and scaffolded approach to teaching writing. It focuses on helping students understand and produce specific text types (or genres) by analyzing their purpose, organizational structure, and language features. In the United States, common genres that students interact with in school include recounts, information reports, arguments, explanations, fictional narratives, and procedures (Brisk, 2015). The primary goal of a genre-based approach is to make the language of learning visible and accessible to all learners (Derewianka, 2015).

This type of instructional approach can be particularly helpful for multilingual learners because it helps students see how language is used differently in various genres (de Oliveira & Iddings, 2014). For example, in an information report unit, students might learn how to use expanded noun phrases to pack information, or technical vocabulary to describe a topic accurately. While in a narrative unit, students might focus on using a variety of verbs to sequence an event. This focus on language within different genres helps multilingual learners understand how language works in context and supports them in applying these features effectively in their own writing.

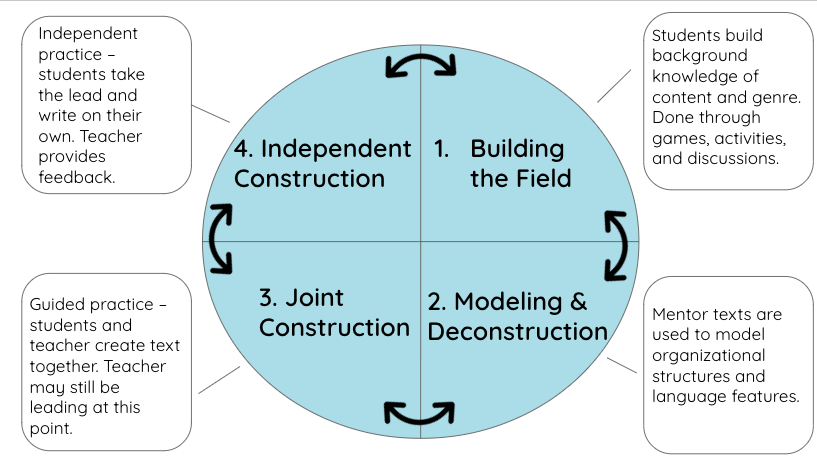

The way that a genre-based approach is implemented in the classroom is through a framework called the Teaching and Learning Cycle (TLC). While there are different models of the TLC, almost all of them share the following four phases: a building the field phase to build background knowledge, a modeling and deconstruction phase to analyze language within mentor texts, a joint construction phase where the teacher and students work together to create text, and finally an independent construction phase, in which students take the lead in and apply what they have learned (Brisk, 2022; Gibbons, 2009). These phases are meant to be used flexibly and revisited as needed to meet the needs of students, as is represented by the double-headed arrows shown in Figure 1.

What does the science of reading say about writing?

While the SoR provides numerous insights into writing—far more than we can cover here—we will focus on the key aspects most relevant to this discussion. LETRS (Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling) is a widely used professional learning program being implemented in schools nationwide (Schwartz, 2022). Grounded in the SoR, LETRS acknowledges that writing is a complex and challenging process, and students must receive explicit instruction to learn to write for a variety of purposes, or genres.

LETRS emphasizes that when learning to write, students must learn both foundational skills, which include letter formation, spelling, punctuation, and spacing between words, as well as composition, which encompasses higher-level skills such as word choice, sentence formation, grammar, organization, and genre awareness (Moats & Tolman, 2019). ESL teachers are trained and experienced in teaching the skills that students need to be skilled writers, particularly within the realm of composition. Overall, the SoR emphasizes that writing instruction should be systematic, explicit, and scaffolded, ensuring that students develop both the foundational and compositional skills necessary to become effective writers.

Making Connections between the science of reading and a genre-based approach

Many of the principles supported within the SoR approach align with the work ESL teachers are uniquely qualified to do. While the SoR encompasses both word recognition and linguistic comprehension, a genre-based approach connects to the latter, as it emphasizes background knowledge, vocabulary, and language structures (Scarborough et al., 2001). ESL teachers, who are experts in teaching language beyond the word level, are well-equipped to integrate SoR-aligned principles while maintaining a focus on developing students’ language and writing abilities. In this section, we will discuss three principles aligned with both the SoR and a genre-based approach—a systematic approach to literacy development, background knowledge, and explicit instruction.

Using a systematic approach to literacy development

Both the SoR and genre-based pedagogy emphasize a systematic approach to instruction. The SoR, for example, advocates for structured, sequential instruction in teaching reading skills (Ehri, 2020). Similarly, a genre-based approach supports writing instruction through the TLC, which provides a scaffolded framework. This structured approach ensures that students are not left to figure out writing through trial and error, but instead receive explicit instruction and support along the way (Brisk, 2015). Both approaches emphasize the importance of a scaffolded and structured progression to facilitate student learning.

Building background knowledge

Background knowledge is an essential component of literacy. Within the SoR, it is recognized as essential for reading comprehension, as students with greater background knowledge on a topic are more likely to understand and engage with a text. A genre-based approach also emphasizes the importance of background knowledge. For example, the TLC includes a Building the Field phase which is intentionally designed to provide students with the necessary background knowledge to deepen their understanding of both the content and the genre they are studying. By integrating background knowledge into instruction, both approaches ensure that students are better prepared to access and produce a variety of texts.

Providing explicit instruction

Explicit instruction is a structured approach to teaching that emphasizes clarity and direct teaching to support learning (Ashman, 2021). The SoR advocates for explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension, while genre-based pedagogy applies it to language and writing. Both approaches underscore the value of scaffolded learning experiences and the gradual release of responsibility. Additionally, both approaches recognize the importance of making the implicit explicit for students to understand and apply literacy knowledge and skills.

What does this look like in the classroom?

This section highlights how one ESL teacher, Ms. Graves, integrated the systematic principles of the SoR with the scaffolded framework of the TLC in a first-grade classroom during a writing unit on animal information reports.

Building the field

To introduce first-grade multilingual learners to the genre of information reports, Ms. Graves had students compare fictional narrative texts with informational texts. Students observed how these two types of texts looked and sounded different. For example, they discussed the differences between a storytelling voice and a teaching voice.

Additionally, students participated in interactive activities to learn about facts versus opinions. Ms. Graves also read multiple information report texts to her students, pointing out how the authors used a teaching voice to tell true information. She also introduced animal-related vocabulary that students would encounter throughout the unit.

The primary objective of this phase was to build background knowledge—both knowledge about the genre of information reports and content knowledge about animals. Ms. Graves knew that this foundation was essential to students’ reading and writing throughout this unit, and would set them up for success as they moved forward.

Modeling and deconstruction

During this phase, Ms. Graves carefully selected a small number of mentor texts to exemplify various organizational structures and language features she wanted her students to apply in their own information report writing. For example, she selected one text that demonstrated how writers can use headings to break one large topic into multiple smaller topics, and another to illustrate how writers add labels to pictures to provide additional information. Ms. Graves guided students in analyzing the language of these texts. She pointed out key language features and facilitated discussions about why authors made specific linguistic choices. Overall, this phase enhanced multilingual learners’ understanding of the language used in information reports. This fostered deeper comprehension when reading informational texts, and also helped them incorporate relevant language features into their own writing.

Joint construction

This point in the TLC allowed Ms. Graves and her students to collaboratively construct a text. At one point in the unit, Ms. Graves’ instructional focus was on breaking a large topic into smaller subtopics. With this in mind, students were divided into three groups for a jigsaw activity. Each group was assigned a specific subtopic for an animal report, focusing on habitat, diet, or appearance. During this phase, Ms. Graves provided ample support to the groups and was still in the lead for much of the writing. Once each group’s subtopic was complete, Ms. Graves put them together and read the final product aloud. This phase of the TLC prepared students to take ownership of their writing in the next phase.

Independent construction

This phase is where the students took the lead on their writing. Each student chose an animal to write about. Ms. Graves reminded students of the mentor texts and their collaboratively written report, then guided them in structuring their own information reports using three familiar subtopics: habitat, diet, and appearance. As students created their reports, Ms. Graves conferred with students to give students feedback and gather formative assessment data, which she used to guide future instruction and provide targeted support based on students’ needs. Upon completion of their reports, students recorded themselves reading their finished work, allowing them to share their finished product with their families.

The TLC provided Ms. Graves with a framework to systematically address students’ language and writing development. Additionally, each phase of the TLC provided Ms. Graves with opportunities for explicit language instruction. For example, Ms. Graves explicitly taught vocabulary, embedded oral language practice, and included modeling and practice with various language structures relevant to information reports. This structured, genre-based approach aligned with SoR principles, empowering Ms. Graves’ students to build confidence and succeed in language and literacy.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while the SoR and a genre-based approach to writing have distinct focuses, they share foundational principles that can be leveraged to support multilingual learners. Both approaches emphasize a systematic approach to literacy development, building background knowledge, and providing explicit instruction. ESL teachers, with their specialized expertise in language instruction, are uniquely positioned to bridge these approaches—ensuring that students not only develop strong reading and writing skills but also gain a deep understanding of how language functions across content areas for various purposes. By integrating these two approaches, ESL teachers can assert their expertise as language educators, providing multilingual learners with the knowledge and skills they need to thrive as readers and writers, preparing them to succeed in the classroom and beyond.

References

Ashman, G. (2021). The power of explicit teaching and direct instruction. Corwin.

Brisk, M. E. (2015). Engaging students in academic literacies: Genre-based pedagogies for K-5 classrooms. Routledge.

Brisk, M. E. (2022). Engaging students in academic literacies: SFL genre pedagogy for K-8 classrooms (2nd ed.). Routledge.

de Oliveira, L.C., & Iddings, J.G. (2014). Genre pedagogy across the curriculum in U.S. classrooms and contexts. In L.C. de Oliveira & J. Iddings (Eds.), Genre pedagogy across the curriculum: Theory and application in U.S. classrooms and contexts. (pp. 1-7). Equinox.

Dehaene, S. (2013, May). Inside the letterbox: how literacy transforms the human brain. In Cerebrum: the Dana forum on brain science (Vol. 2013). Dana Foundation.

Derewianka, B. (2015). The contribution of genre theory to literacy education in Australia. Faculty of Social Sciences – Papers. 1621. https://ro.uow.edu.au/articles/chapter/The_contribution_of_genre_theory_to_literacy_education_in_Australia/27690756

Ehri, L. C. (2014). Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning. Scientific studies of reading, 18(1), 5-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2013.819356

Ehri, L. C. (2020). The science of learning to read words: A case for systematic phonics instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1), S45-S60. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.334

Froemming, A. (2023). Exploring how elementary ESL teachers experience learning and change related to a genre-based approach to language instruction. School of Education and Leadership Student Capstone Theses and Dissertations, Hamline University. Digital Commons. https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/hse_all/4588/

Gibbons, P. (2009). English learners academic literacy and thinking. Heinemann.

Gough, P. B. (1972). One second of reading. Language by ear and by eye. MIT Press.

Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258600700104

Harper, C., de Jong, E., & Platt, E.. (2008). Marginalizing English as a second language teacher expertise: The exclusionary consequence of No Child Left Behind. Language Policy, 7(3), 267-284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-008-9102-y

Liggett, T. (2010). “A little bit marginalized”: The structural marginalization of English language teachers in urban and rural public schools. Teaching Education, 21(3), 217-232. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476211003695514

Moats, L. C., & Tolman, C. A. (2019). LETRS: Language essentials for teachers of reading and spelling (3rd ed.). Voyager Sopris Learning.

National Education Association. (2024, September). The science of reading: Laws and policies across the states. NEA Today. https://www.nea.org/nea-today/all-news-articles/science-of-reading

Scarborough, H. S., Neuman, S. B., & Dickinson, D. K. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. Handbook of early literacy Research, 1, 97-110.

Schwartz, S. (2022, July 20). What is LETRS? Why one training is dominating ‘Science of Reading’ efforts. Education Week. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/letrs-program-teacher-training

Seidenberg, M. S., & McClelland, J. L. (1989). A distributed, developmental model of word recognition and naming. Psychological Review, 96(4), 523-568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.523