Demonstratives (this, that, these, those) are pointing words: In conversation they typically point to people and things but in written expository text, they often point to ideas, events, and situations. ESL teachers need to help their students gain familiarity with the functions of demonstrative reference beyond simple pointing and contrast.

Keywords: demonstratives, reference, elementary, middle school, secondary, teacher education

Imagine you are working with your fourth grade English Learners (EL) as they read a science unit on the engineering process. You’ve worked with them on figuring out what noun phrases with articles refer to (the answer, the lesson) in written texts, and they’ve mastered demonstratives (this, that, these, those) for pointing to people and objects, but as you preview their textbook science lesson (see Figure 1), you see a need to bring these two topics together: How do demonstratives in written expository texts refer to entities?

The text in Figure 1 provides some helpful examples to start us on our way to answering that question.

This robot is riding a bicycle, just like a human, and not falling over. How is this possible?

In the first example, the demonstrative determiner this before the noun robot tells the reader to look nearby for a salient referent. Even if the word robot is not familiar to the reader, the white thing on the bicycle is a very obvious nearby choice for the referent since it is foregrounded in the image. In the second example, the demonstrative pronoun this also tells the reader to look nearby for a referent, but in this case its referent is less obvious. This refers to the whole previous sentence, the idea that a robot can ride a bicycle and not fall. Referring to ideas is a common function for demonstratives and one that they perform far more efficiently than noun phrases with articles. Imagine what the question How is this possible? would look like without the demonstrative (1).

(1) How is the robot riding a bicycle possible?

How is it possible for the robot to ride a bicycle?

How is the situation where the robot rides a bicycle possible?

Long phrases and complicated syntax can result from using a structure other than a demonstrative to refer to an idea. In contrast, demonstratives provide a concise and efficient way to refer to ideas, which is one reason they are important in the English system of reference. Clearly, ELs need to be able to figure out what demonstratives refer to as they read academic texts as well as being able to use them appropriately in their own writing. The purpose of this article is to provide English as a Second Language (ESL) teachers with information about how demonstratives are used in written academic texts in order to inform their teaching. Basic information about English demonstratives is presented first, followed by a review of typical ways that demonstratives are used in expository academic texts, drawing on examples from 4th and 5th grade science textbooks and a high school history textbook.

Basic info about demonstratives

The words that and this are considered part of a basic 2000-word English vocabulary, and they are, respectively, the tenth and thirty-fourth most frequent words in the Cambridge International Corpus of spoken and written English (O’Keefe et al., 2007). That occurs more frequently than this because it has additional functions such as introducing adjective clauses (the dog that ate a banana) and noun clauses (I think that Eric’s doughnut fell in the dishwasher). In this paper, only the demonstrative uses of this and that will be discussed. But the relative frequencies of that and this are not just due to the additional functions; in conversation, the pronoun that occurs far more frequently than this (more than 10,000 occurrences per million words while this is <2000; Conrad & Biber, 2009). Specifically, that is used to evaluate an idea or validate the correctness of a claim (that’s right, that sounds better). In academic writing, this has about double the use of that (more than 2,000 occurrences per million words for this compared to about 1,000 for that; Conrad & Biber, 2009). Similar to that in conversation, this in academic writing often refers to an idea that was just stated; the next section describes how this is done and the complications that arise.

The usage of demonstratives most commonly taught in ESL textbooks is the basic, common one of pointing to people and objects while speaking (Schiftner & Rankin, 2012). Typically, such textbooks focus on the near/far distinction of this and that (Cowan, 2008); some advanced textbooks (e.g., Larsen-Freeman, 2007) cover the reference usage of demonstratives in written text, but as the bicycle-riding robot text shows, ELs are likely to encounter demonstrative reference in writing well before they reach an advanced level, and teachers need to be prepared to teach this topic across a range of grade and proficiency levels.

What demonstratives do in written academic expository texts

Just as demonstratives and their accompanying gestures in conversation tell the listener where to search for the referent in terms of distance, so too do demonstratives in academic texts. However, in writing, the distance becomes more abstract and the referent harder to find with no physical gesture and only a demonstrative pointing the way. This section starts with examples where the referents are easier to find and moves on to more abstract ones.

Referring to current context

In the sample texts reviewed for this article, the demonstrative determiner this is often used to refer to the context in which its sentence is embedded (2) and to help students organize their learning.

(2) As you read these two pages, underline…

Find the answer to the following questions in this lesson.

As you read about the rise of democratic ideas in this prologue, think about…

Examples as in (2) are relatively easy to spot since they a) are quite similar to oral “pointing,” b) always show nearness (this, these), and c) include vocabulary that names parts of the text (pages, lesson, prologue) and directions to the reader (underline, find, think). In addition to referring to their written ‘container’ (these two pages, this chapter), such demonstratives may also refer to their time ‘container’ (this week), although the latter usage is more common in speaking (Maes et al., 2022).

Similarly, this and these are frequently used to refer to a nearby image or part of it, as shown in Figures 2 and 3. In Figure 2, several visual and verbal clues make the referent of these round disks relatively obvious: The left-pointing arrow, the nearness of demonstrative and image, the adjective round, and the plural disks all work together to identify the referent.

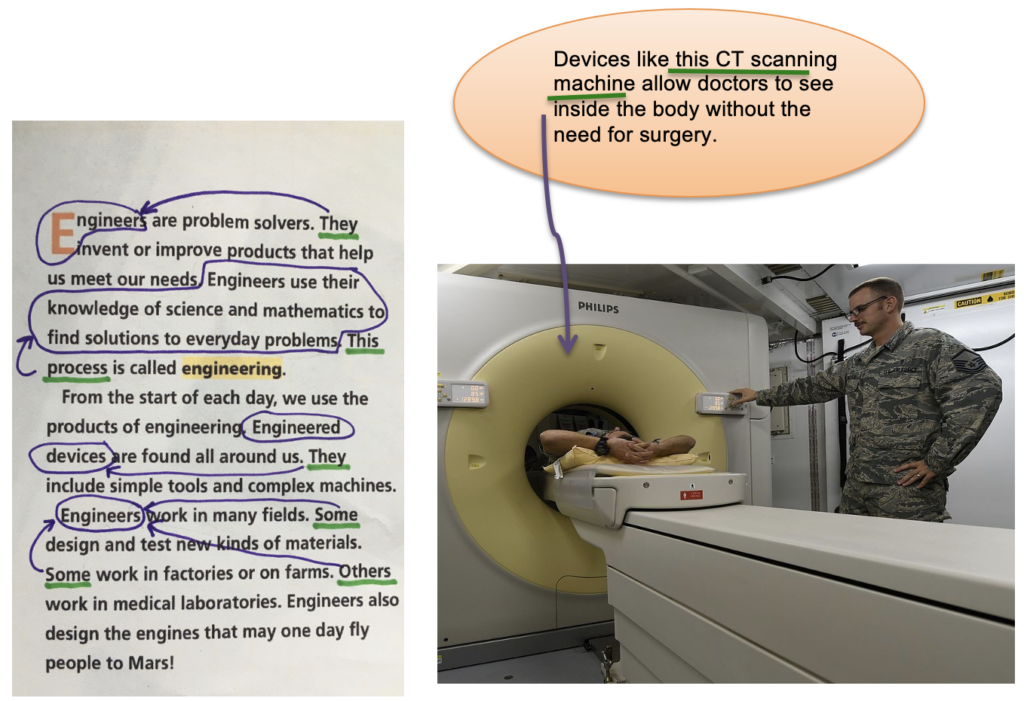

In contrast, the demonstrative this in Figure 3, which is adapted from a science textbook, has somewhat limited clues as to its referent. The proximity of the verbal and visual texts is again important, but the arrow points unhelpfully to the verbal text. Previous pages in the science textbook presented multiple examples of technology and the needs they meet, so the reader will need to recognize several types of technology in the image (helmet, watch, shoes, skateboard, etc.) and identify the one that is “a lot of fun.”

A teaching strategy for demonstratives referring to images could be implemented when teachers draw students’ attention to the visual features of a text as part of a during-reading activity. Specifically, teachers can help students identify the verbal and visual cues for referents, and connect this to a good reading strategy of using the surrounding context to make sure information is understood.

Implying contrast

Most of the demonstrative examples in the sources for this study are this/these, showing nearness, and when that/those are used, it is often (but not always) for an implied contrast. In the fourth grade science text in (3), those is used to contrast failing design features with good ones, without any use of these to make the contrast explicit.

(3) Redesign takes advantage of all work done before. Good design features are kept, and those that fail are discarded.

Similarly, in the history text (4), those, referring to reformers, implies a contrast to a group of people who did not want reform, but without even mentioning them.

(4) The Reformation was a religious reform movement that began in the 16th century. Those who wanted to reform the Catholic Church were called Protestants, because they protested against the power and abuses of the Church.

It’s also important to note that in both of these cases, the full noun phrase that those modifies is implied (those design features, those people), potentially causing some difficulty.

Teachers can connect these implicit contrasts with explicit ones that students are familiar with from classroom talk. It would also be helpful to model how implicit contrasts are used in conversation, for example, how those are yours may imply the existence of some others that are not yours.

Tracking and labeling

Like the definite article the, in the sample texts demonstratives are used to track referents, which means that a noun phrase is introduced, then the head noun is repeated with the or a demonstrative. In the history text in (5), a brilliant cultural movement is tracked with the phrase this movement, using this instead of the to add focus to the referent.

(5) In the 1300s, a brilliant cultural movement arose in Italy. Over the next 300 years, it spread to the rest of Europe, helped by the development of the printing press. This movement was called the Renaissance.

Instances of tracking are relatively easy to follow, given the noun repetition. Slightly harder to follow are cases in which an author uses a synonym or general noun with a demonstrative to refer to objects or people just mentioned (6).

(6) When coal burns, harmful ash and gases are produced. The potential harm these substances can cause leads to negative feedback.

The use of the demonstrative determiner these signals to the reader that the referent is nearby; using the substances would not signal nearness and may cause readers to wonder what substances the author means. In addition to movement and substances, other general nouns that were used for tracking in the science and history sources for this article include ideas, things, practice, act, groups, knowledge, devices, process, items, and tasks.

The cases that are hardest to follow are where demonstratives are used to label stretches of preceding text in order to discuss them further. Labeling is common in academic texts because it gives names to ideas and events that are presented (Francis, 2002), thus stressing their importance. Such a discourse label (using Francis’ terminology) also creates a link between the description of an idea or event (likely long and complex) and the surrounding discussion of it. For example, in (7), the discourse label this event names the action in the second clause of the preceding sentence and links it to a timeline of Judaism that the history text is developing.

(7) The Bible states that God gave the code to the Israelite leader, Moses, in the form of the Ten Commandments and other laws. This event is believed to have occurred sometime between 1300 and 1200 BC.

Understanding text with discourse labels is complicated. First, the reader needs to understand that the referent is not just one object or person named by a concrete noun, rather it is an abstraction. Second, the reader needs to find the stretch of text describing the abstraction. That text may be a sentence or part of it as in (7), or it may be more than one sentence as in (8).

(8) Cell phone technology changes fast, and some people switch to new models after just a few months. More resources are used up, and the old phones sometimes end up in a landfill. This risk is environmental.

Another possible difficulty is that the referent is not clearly stated in the text but has to be inferred (Cornish, 2018). An example of this is shown in (9), an excerpt from a fourth grade science textbook unit where students are being introduced to the design process for engineering.

(9) It has been said that necessity is the mother of invention. But once you find a need, how do you build your invention? That’s the design process.

The demonstrative pronoun that refers to the as-yet-undescribed steps for building an invention to meet a need, as implied in the question.

In addition, a discourse label can also tell the reader how to interpret the referent, like (8) does, where this risk guides the reader to view the situation stated in the previous two sentences as a problem. Example (8) also illustrates another complication with discourse labels: They are often used in text where the author is building an argument (Francis, 2002), meaning that the reader has to determine how the event or situation fits into the bigger picture.

The circumstances where teachers refer to facts, ideas, etc., with demonstratives in oral classroom language can be a jumping-off point for explicitly teaching how demonstratives in written academic language are used to track and label referents. Teachers should compare that in speaking with this in writing and explicitly point out that demonstratives often refer to ideas stated in clauses, sentences, or even more than one sentence rather than to something represented by a noun alone. They should also point out clues in demonstrative + general noun phrases (these substances, this process) that help identify the referent. In post-reading activities, when students are highlighting pronouns and then drawing chains of reference, as in Figure 4, they should be working with the visual and verbal texts together and including demonstratives to create a more complete picture of reference.

Although demonstratives are not used nearly as often as articles for referring, they occupy a unique spot in the English reference system because they so frequently refer to ideas, events, and situations––a topic that is not covered by teaching demonstratives for contrast in oral language. Teachers should also recognize that while the pointing function of demonstratives is the same in oral and written texts, the choice of demonstrative is related to the text genre, such as expository or narrative (Maes et al., 2022), so that teaching demonstrative usage with a variety of text types, both oral and written, is vital for ELs’ understanding.

Acknowledgments

I thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and Steve Wicht for his thought-provoking questions.

Notes

- This image, which was originally posted to Flickr, was uploaded to Commons using Flickr upload bot on 27 August 2009, 12:42 by Dorieo. The image and licensing information are available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Athenian_Secret_Ballot.jpg

- Public domain image downloaded from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Skateboard_facility_at_Guantanamo.jpg

- Public domain image downloaded from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:New_CT_scanner_bolsters_medical_capabilities_in_theater_161121-F-NN480-0002.jpg

References

Beck, R., Black, L., Krieger, L., Naylor, P., & Shabaka, D. (2012). Modern world history: Patterns of interaction. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrievable from https://my.hrw.com/SocialStudies/ss_2010/downloads/htmlfiles/content/Modern_World_History_Unit_1.pdf

Conrad, S., & Biber, D. (2009). Real grammar: A corpus-based approach to English. Pearson Education.

Cornish, F. (2018). Anadeixis and the signalling of discourse structure. Qua-derns de Filologia: Estudis Lingüistics, XXIII, 33-57. https://doi.org/10.7203/qf.23.13519

Cowan, R. (2008). The teacher’s grammar of English: A course book and reference guide. Cambridge University Press.

DiSpezio, M., Frank, M., Heithaus, M., & Ogle, D. (2017a). Science fusion: Fifth grade student edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

DiSpezio, M., Frank, M., Heithaus, M., & Ogle, D. (2017b). Science fusion: Fourth grade student edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Francis, G. (2002). Labelling discourse: An aspect of nominal-group lexical cohesion. In M. Coulthard (Ed.), Advances in written text analysis (pp. 83-101). Routledge.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2007). Grammar dimensions 4: Form, meaning and use (4th ed.). Thomson Heinle.

Maes, A., Krahmer, E., & Peeters, D. (2022). Explaining variance in writers’ use of demonstratives: A corpus study demonstrating the importance of discourse genre. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 7(1), 1-36. https://doi.org/10.16995/glossa.5826

O’Keefe, A., McCarthy, M., & Carter, R. (2007). From corpus to classroom: Language use and language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Schiftner, B. & Rankin, T. (2012). The use of demonstrative reference in English texts by Austrian school-age learners. In Y. Tono, Y. Kawaguchi, & M. Minegishi (Eds.), Developmental and crosslinguistic perspectives in learner corpus research (pp. 63-82). John Benjamins.