Five years have passed since Minnesota’s adoption of WiDA, yet teachers are still adjusting to its instructional and collaborative shifts when in working with their students and colleagues. In one school district, WiDA’s constructivist nature has promoted powerful partnerships between classroom and EL teachers, by coupling the structure of Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) and language assessments.

“What grade level team should I sit with?” I asked my principal.

It was week two into the new school year and PLC grade level teams were analyzing the fall’s Developmental Reading Assessment (DRA) scores.

“Well, which grade will you be spending the most time with?”

“… Grade 2? I think I will sit with the grade 2 team.”

I was the only English Learner (EL) teacher in my elementary building with six grades to support. Being the sole EL instructor in the school presented some obvious challenges, but none was more acute than becoming a meaningful part of a grade level Professional Learning Community (PLC) team. Reading and Math data were continually scrutinized, leaving conversations about language growth a footnote at best. Besides the yearly state language assessment and student proficiency levels, the data I offered paled in comparison to Developmental Reading Assessment (DRA), Measures of Academic Progress (MAP), and Minnesota Comprehensive Assessment (MCA) scores. When the conversation steered to language acquisition, it was always coupled with reading: “How does that affect their reading? What are some ways you can support their reading?” I politely replied that once students gained better facility in their oral language, then they would be able to improve their literacy skills. “Okay, but will you also work on this digraph with your kids this week in addition to whatever you are working on? Because technically, you are their second scoop of literacy instruction.” Second scoop. No longer were these words associated with the sweet taste of Ben and Jerry’s ice cream but with the misperception of my role as a language educator.

Shifts in the Field

In the years since my underwhelming PLC experience, three major shifts have prompted important changes in our district’s approach to collaboration, instruction, and assessment. The WiDA and Common Core (English Language Arts) adoptions promoted new understandings about academic language acquisition and its effect on content learning. Working in tandem, these two adoptions prompted an urgency to teach academic English in conjunction with content curriculum (Zwiers, O’Hara & Pritchard, 2013). The second shift was a creation of language assessments to measure academic language growth during the school year (Zwiers et. al, 2013). These performance-based language assessments demonstrated how students can access content learning within their current language level (Gottlieb, 2012). The third and final shift called for utilizing language assessments as a student-focused collaboration tool between content and EL teachers (Gottlieb, 2012).

These shifts perpetuated change in instruction, collaboration, assessment, and prompted a more equitable role for the EL teacher within the PLC grade level team. While this article describes specific changes our district made to accommodate the three shifts, it can also serve as a pathway for other schools and/or districts to facilitate meaningful collaboration around English Learners.

Shift #1: English Language Development in Partnership with Academic Achievement

The WIDA (2012) and Common Core State Standards in ELA, both adopted by Minnesota in 2010, were the first of three shifts that emphasized the role of language acquisition in student learning. The WIDA adoption specifically called for assessment, instruction, and collaboration focused on language acquisition in partnership with, not in the shadow of, academic achievement. WiDA’s framework demanded the need to analyze and specify varying linguistic structures within different subject areas and heightened the frequency that focused language teaching, appropriate scaffolds, and practice should occur throughout the school day.

As a result of WiDA, EL instruction has undergone a reimaging process. EL is no longer a “second scoop” of guided reading nor is it a language intervention. Language learning is continuous, ongoing and requires the support of both English learner and classroom teachers. While the new standards increased opportunities for language instruction, it also presented challenges, specifically for schools without preset collaborative structures between classroom and EL teachers (Hingsfeld & Dove, 2015). As the only EL teacher in the building, I wondered how I could foster language development throughout all content areas. How could I meaningfully collaborate with my classroom colleagues, encourage them to incorporate opportunities for language support and practice within everyday instruction when I did not have a place at the PLC table?

Shift #2: Language Assessments Drive Instruction and Collaboration

In Accountability in Action: A Blueprint for Learning Organizations, Reeves (2000) compares summative assessments to an autopsy. Reeves states, “summative assessments, like an autopsy, can provide useful information that explains why the patient has failed, but the information comes too late[…]” (paraphrased in Dufour, Dufour, Eaker & Many, 2010, p. 75). My annual language proficiency assessment, then Test for Emerging Academic English (TEAE)/Student Oral Language Observation Matrix (SOLOM), and now Assessing Comprehension and Communication in English State-to-State for English Language Learners (ACCESS), was a corpse. It was an odorous, overused cadaver of language acquisition data I carried into my September PLC meeting that I assumed my colleagues would view as current and useful.

“Here is my really old data from last March,” is what I should have said. Looking back, I couldn’t blame my colleagues for quickly moving through five-month old ACCESS scores to fresh, days old DRA data to accurately plan for the coming weeks ahead. I needed an assessment administered within those first two weeks of school to contribute meaningfully the PLC conversation. To earn a place at the table, I needed a current language assessment.

Reeves (2000) does not leave the autopsy analogy without resolution. The relationship between a summative assessment and autopsy is parallel to the relationship between formative assessment and a physical exam. Summative assessments provide useful information when the patient has failed, whereas formative assessments inform both physician and patient (or teacher and student) of current data to aid important next steps and decision-making. Though ACCESS scores successfully determined important program decisions and provided student proficiency profiles, the scores were not current enough to prescribe necessary next steps—too many months had passed. My summative scores needed a common language assessment partner.

In Common Language Assessment for English Learners, Gottlieb (2012) characterizes formative assessment as a critical piece of instruction: “common language assessment allows English learners to demonstrate the extent to which they have the language requisite for accessing grade-level content” (p. 6). When utilized in partnership with content teachers, either embedded within the unit itself or as an analytical piece, formative language assessments allow classroom teachers to better understand the complexities of academic language and how language may hinder access to core curriculum. When implemented within a classroom, school, or district, language assessments can:

- Inform language instruction

- Help teachers better understand the relationship between language and academic achievement

- Provide reliable, valid, and timely language data for low-stakes decision making

- Allow for greater equity in classrooms with English learners (Gottlieb, 2012).

To engage in meaningful, collaborative conversations regarding the role of language acquisition and its impact on academic achievement, conversations must stay student-centered. Language assessments maintain focus on students’ academic language growth while offering insight into content area comprehension. Teachers analyze student language data and converse on best practices or strategies to scaffold for language support or even incorporate language development opportunities within core instruction. In Gottlieb’s (2012) words,

by having information available across classrooms, teachers can have substantive conversations on the effectiveness of their instructional approaches and their impact on students; in essence, they can better analyze what they teach, how they teach, and how well they teach” (p. 8).

Using Language Functions to Identify Language Demands In Content

During the creation of these language assessments, the curriculum writing team had to take many factors into consideration. First, to make these assessments useful for both EL and classroom teachers, our curriculum writing team had to deeply analyze the language demands of the Minnesota academic content standards. Upon our examination, we discovered that content standards use language for functionality. Most standards began with a language function word or phrase: express content knowledge, communicate, analyze and interpret and so on. WiDA drew upon the work of Derewianka (1990) to build the theoretical foundation underlying its standards framework. Derewianka’s functional view of language and its communicative purpose is paraphrased as: “The advantage of a functional approach is that language is not taught for its own sake; rather, it demonstrates how language operates in all areas of the curriculum (WiDA Standards Framework and its Theoretical Foundations, p. 2).”

Functions organize and specify required language to access academic content. When language functions are purposely used within objectives, instruction, and assessment, students not only can execute the academic task, but they also can grow in their English Academic Language Development. Utilizing language functions as the organizational feature in common language assessments creates clear pathways to provide language development and support academic achievement. For example, our first grade assessments focus on the language of retell. To help students give a sophisticated (yet developmentally appropriate) retell, students are instructed in a variety sequential language structures, descriptive words and phrases, and sentences that show emerging complexity. When this is done in conjunction with the ELA content objective, students are able to better demonstrate their understanding of the text, complete the academic task, and grow in their academic English.

The research and guidance of Gottlieb and Derewianka provided a structure for district language assessments. Our curriculum writing team wanted our assessments to act as dipstick and provide a snapshot of language growth in schools across our district. There were many aspects to take into consideration but our conversations kept circulating back to writing. As a modality it is often the most challenging for students to master and was the weakest in ACCESS results. For our first stab at common language assessments, writing would be our focus.

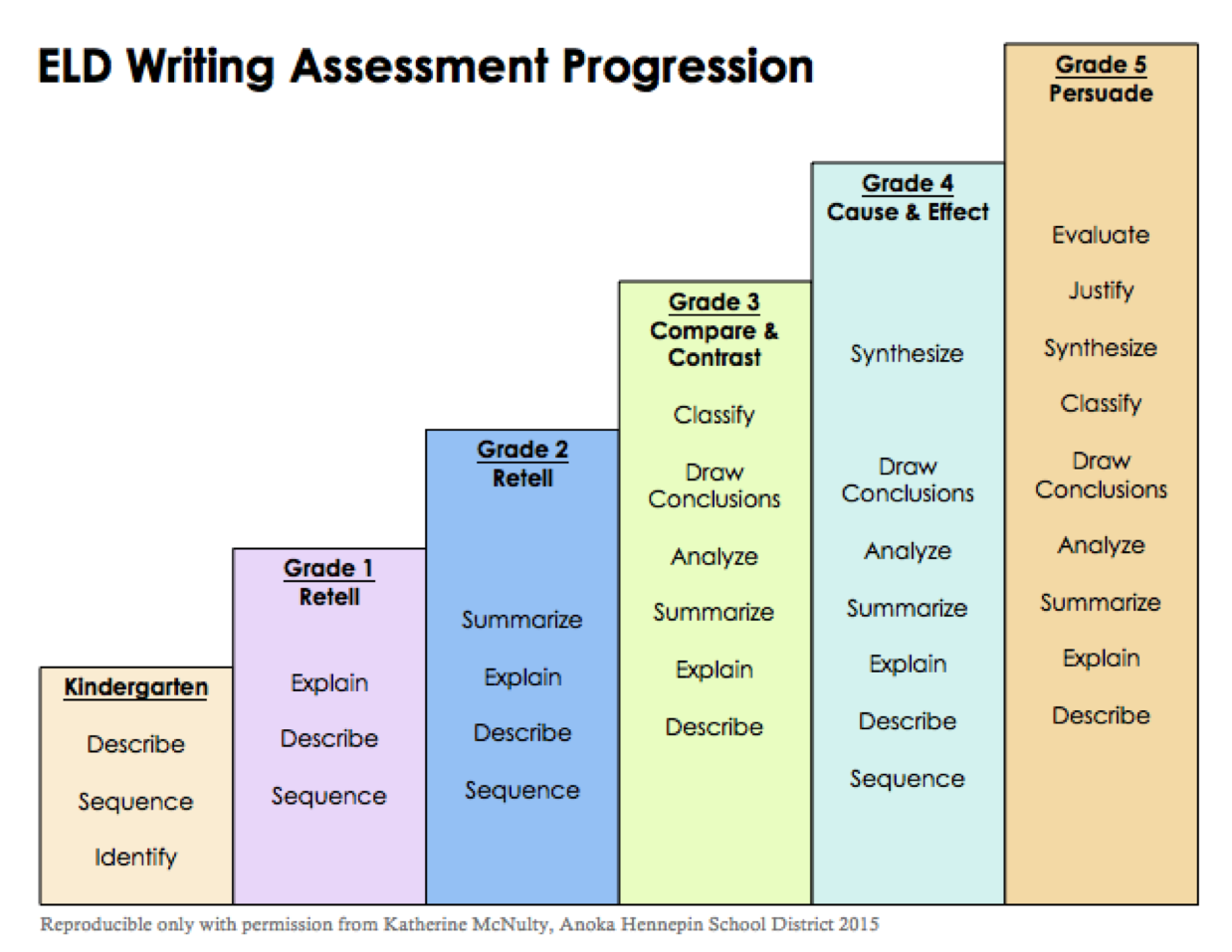

A challenging aspect of our school district is its heterogeneous English Learner populations in both languages spoken and population. Some sites have as many as six teachers while many only have one. Our team had to find a way to create common assessments that would measure language growth and provide a connection to academic content. Our conversations led to a language analysis of academic content standards and district curriculum. Language functions organized most academic content standards, district curriculum and thus specified the language students would need to engage meaningfully within their academic classrooms. Moreover, we discovered that certain language functions occur often in grade levels across subject areas. Primary grades placed a greater emphasis on describing, sharing, and retelling information or stories. Intermediate grades focused on more advanced uses of language, such as analysis, argumentation and synthesis.

After a lot of conversation, language function sorting, and standard reviewing, we organized our written assessments as seen in Figure 1. With the exception of Kindergarten, one language function remains the focus throughout the year, but within that focus is an inclusion of other supportive functions. In order to provide a solid retell, first graders must explain, describe and sequence, but as second graders, summarization becomes more commonplace, thus increasing the rigor of the assessment.

Shift #3: Using Language Assessment to Eradicate Instructional Silos

Many types of collaborative educational partnerships may feel like arranged marriages (TESOL, 2013). Grade level teams are assembled, professional development is delivered, and student improvement goals are written, all during teacher workshop week. During this time, EL teachers do a delicate dance of making schedules, groups, and deciding when, where, and how ELD instruction is going to take place. Creating a meaningful partnership between teachers requires communication, student-focused instruction, and an assumption of positive intent (Honingsfield & Dove, 2015). These facets promote a compatible arranged marriage of teacher collaboration and demote silos (Zwiers et. al, 2013).

Beyond the basic aspects of teacher collaboration, MN ELD standards prompted a new role for EL teachers—instructional coach (TESOL, 2013). If we expect classroom teachers to include language development within their teaching and without an EL teacher present, this type of job-embedded professional development is key. In their interactions with classroom teachers, the EL coach has an opportunity to observe, question, and reflect on student progress in a way that promotes cognitive shifts about how language and content learning intertwine. The PLC structure, partnered with formative assessments and its focus on student achievement enables these intentional conversations to happen.

Dufour, Dufour, Eaker & Many (2010) write extensively regarding the need for formative assessment to drive instruction and improve student performance within the context of a PLC.

One of the most powerful, high-leverage strategies for improving student learning available to schools is the creation of frequent, high-quality, common formative assessments by teachers who are working collaboratively to help a group of students to acquire agreed-upon knowledge and skills…They [Assessments] can provide helpful information regarding the strengths and weaknesses of curricula and programs in a district, school, or department, and they often serve as a means of promoting institutional accountability. (p. 75)

With the writing assessment in hand, EL teachers can use powerful language acquisition data to enrich PLC conversations and promote changes in instruction.

Conclusion

Looking back at my experience with the second grade PLC team, I realize how helpful a language assessment would have been. Many of our students plateaued in their DRA levels because they lacked the necessary language to give a detailed, sequenced, and descriptive retell. While this was a discussion between my colleagues and myself, if I had my formative writing assessments, together we could have analyzed what students wrote in conjunction with the language demands of that particular DRA level. From there, we would have made an instructional plan in both content and ELD instruction to support their language learning. Perhaps, now they’d take my feedback about working on sequential signal words, complex sentence structure or descriptive vocabulary. Without the data in hand, however, my knowledge was viewed as an opinion and observation, not as hard evidence.

Now an official EL instructional coach for my district, I have seen the writing assessments utilized as a strong data point in teacher collaboration. PLC conversations are focused on student learning and have created shifts in core instruction. The acquisition of academic English is becoming a shared responsibility beginning with dedicated teachers and their powerful partnerships with one another. Although it has almost been five years since the WiDA adoption, its ripple effects are eradicating instructional silos and streamlining instruction through strong teacher collaboration focused on dual language growth and academic achievement data.

Of course, there is still work to do—many partnerships struggle to grow in the day-to-day organized chaos that is teaching. Many PLC conversations still focus on reading and math with little room for the role of language acquisition in student learning. However, language assessments provide an alternative answer to the essential PLC question: How will we respond when students don’t learn? Language assessments prescribe better solutions. They provide a solid groundwork for productive, focused, collaborative conversations and instructional steps for the ones that matter most—our learners.

References

Dufour, R., Dufour, R., Eaker, R., & Many, T. (2010). Learning by doing: A handbook for professional learning communities at work. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Gottlieb, M. (2012). Common language assessment for English learners. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Honigsfield, A. & Dove, M.G. (2010). Collaboration and co-teaching: Strategies for English learners. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Honigsfield, A. & Dove M. G. (2015). Collaboration and co-teaching for English learners: a leader’s guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Reeves, D. B. (2000). Accountability in action: a blueprint for learning organizations. Denver, CO: Advanced Learning Press.

Implementing the Common Core State Standards for English Learners: the changing role of the ESL teacher. (2013). TESOL International Association. Retrieved from www.tesol.org.

2012 amplification of the English language development standards, kindergarten-grade 12. (2012). WIDA Consortium. Madison, WI: Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System.

The WIDA standards framework and its theoretical foundations. (2014). WIDA Consortium. Retrieved from www.wida.us.

Zwiers, J., O’Hara, S., & Pritchard, R. (2013). Eight essential shifts for teaching Common Core Standards to academic English learners. Retrieved from www.aldnetwork.org.