Our teacher-researcher team used pedagogical translation to incorporate translanguaging pedagogy into K–12 sheltered multilingual classrooms and engage students in effective literacy practices across all subject areas.

Keywords: middle school, teacher education, multilingual pedagogy, translanguaging

Translanguaging is an emerging concept in K–12 multilingual classrooms, and professional development may encourage teachers to incorporate more multilingual pedagogy into their lessons. But sometimes, it is more complicated to imagine what that pedagogy actually looks like when you’re halfway through fifth period and trying to teach social studies with a class of middle schoolers. This article comes from a collaboration between a team of middle grade English language learner (ELL) teachers who teach sheltered content classes, one of whom co-authored this paper, and a team of language and literacy researchers. We used an existing multilingual literacy framework called TRANSLATE to collectively explore ways of bringing translanguaging theory into meaningful classroom pedagogy to honor all multilingual students’ languages while increasing metalinguistic awareness.

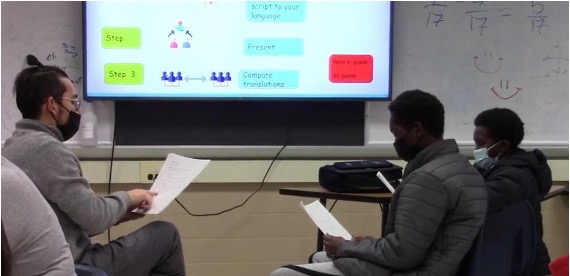

We understand translanguaging to describe both a theory of language and a pedagogical practice (García & Kleifgen, 2019). As a theory of language, translanguaging rejects the idea of languages as strictly separate systems in the mind of the multilingual individual. Rather, multilinguals are understood to have one, cohesive meaning-making system and draw strategically from their entire linguistic repertoire to communicate. As a pedagogy, translanguaging describes the practice of engaging students in fluid, student-centered multilingual interaction that leverages this unitary linguistic repertoire to improve student understanding, engagement, and learning (García & Kleifgen, 2019). This foundation helped us lay the groundwork to collaborate with a team of ELL teachers to adapt TRANSLATE in their sheltered math, social studies, English language arts (ELA), and science classes. Students worked in small groups or activity centers in both pull out and whole class activities. Universally, bringing all of students’ language practices into the classroom was a tremendous learning experience for students, teachers, and researchers. This article centers the instructional adaptations and material design of four of these teachers, and describes how their experience with pedagogical translation increased their awareness of students’ linguistic backgrounds and facilitated teacher curiosity, which in turn led to questions that supported critical thinking around metalinguistic awareness by students.

Introducing TRANSLATE

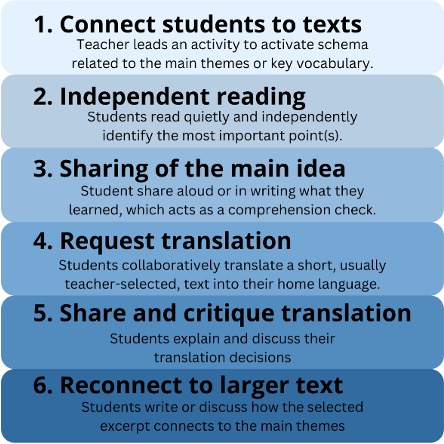

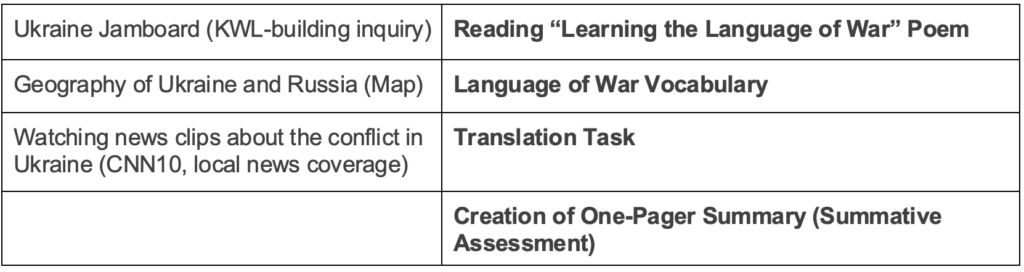

The TRANSLATE protocol was developed as a literacy intervention for multilingual students (Goodwin & Jiménez, 2015). It was adapted from guided reading instruction, which asks students to connect with a grade-level English language text, independently read, and share main ideas. Then, the TRANSLATE protocol prompts students to translate a focal line into their home language and then compare and discuss their translation choices with classmates (preferably those who share home languages). Finally, students consider how these specific sentences connect to the text’s theme (see Figure 1).

The final three steps of TRANSLATE encourage multilingual students’ engagement in the literacy practices of highly proficient readers. This includes negotiating for meaning, focusing closely on text structure, and increasing metalinguistic awareness. Metalinguistic awareness is broadly defined as the ability to consciously reflect on the nature of language (Malakoff & Hakuta, 1991), and in this case, how multiple languages relate to each other.

When students negotiate to create collaborative translations and articulate their translation choices, they tap into knowledge of all their languages and make visible the often tacit metalinguistic understandings about how their languages relate and communicate meaning. Additionally, the TRANSLATE protocol creates opportunities for teachers to learn more about their students’ language backgrounds and abilities.

TRANSLATE in sheltered content classrooms

The study took place at an urban middle school in the upper Midwest, where the ELL teacher team was very supportive of the idea of multilingualism as an asset. In practice, while teachers validated students’ linguistic knowledge and allowed them to code switch to facilitate communication and understanding, few instructional activities were explicitly designed to have students use their home languages to complete academic tasks.

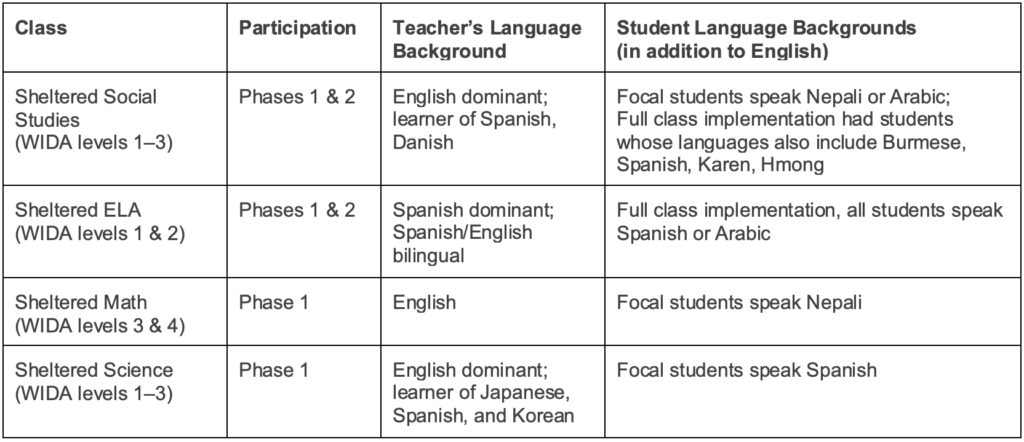

As shown in Table 1, the study included two phases: an initial phase in which the EL team participated in professional development and each teacher tried out the approach with small, homogeneous language groups in pull-out lessons; and a second phase in which two teachers incorporated the approach in content-focused units in their linguistically diverse classes. Data collection in phase 2 centered on focal student groups with homogeneous language backgrounds within each class. For this article, however, we focus primarily on teachers’ design ideas for adapting TRANSLATE into diverse content classrooms, and on what they learned from engaging in this work.

Starting in early October, the teachers began establishing multilingual norms in their classrooms and making space for students to publicly use all their language knowledge. They deliberately highlighted multilingualism by creating multilingual word walls, providing multilingual dictionaries, and facilitating multilingual collaborative dialogues, to name a few. Students’ reactions were positive, though some also were reluctant to engage, which teachers ascribed to students’ understanding of the implicit monolingual norms of the school. This norming process took place over several weeks. Then, teachers introduced TRANSLATE in coordination with their lesson objectives.

In November, the professional learning community (PLC) collaboratively planned and implemented small group TRANSLATE “try-outs” in science, ELA, math, and social studies lessons. This was the first time TRANSLATE had been adapted for STEM (i.e., science, technology, engineering, and math) subjects in any K–12 educational context, and it was particularly exciting to see how teachers leveraged the protocol in these areas. Below, we highlight how teachers adapted TRANSLATE in the science and math classrooms.

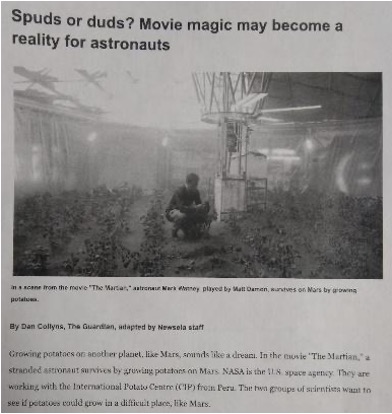

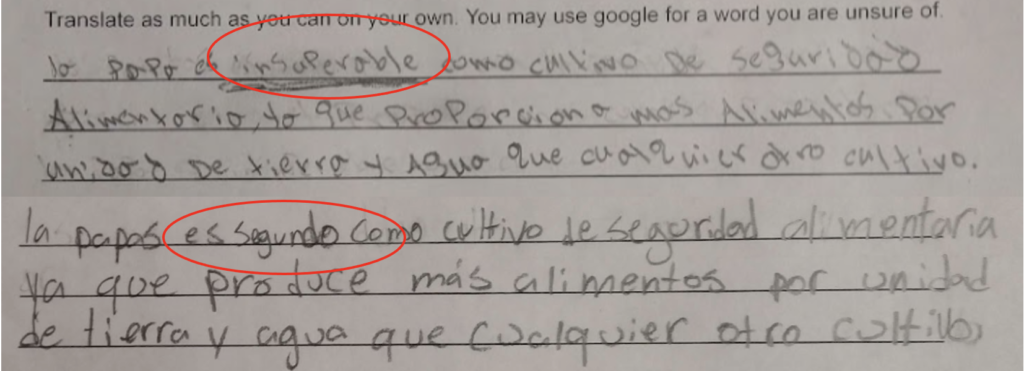

The science adaptation looked similar to how TRANSLATE has been used in literacy classrooms (see Figure 2). Four students participated in the TRANSLATE lesson, all of whom shared Spanish as a home language. After reading a content and level-appropriate text collectively, the teacher asked pairs of

students to translate a focal sentence and compare their translations.

Focal sentence: “The potato is second to none as a food security crop as it produces more food per unit of land and water than other crops.”

Student Translations:

In the translations, students interpreted “second to none” quite differently. One student said the potato is insuperable (‘unbeatable’) while the other translated the text as segundo (‘second’). These differing interpretations sparked conversation on word meaning and use.

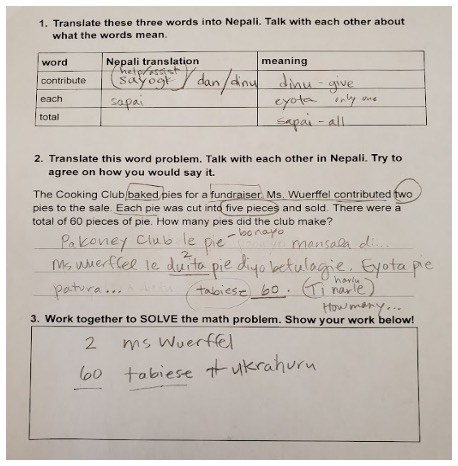

TRANSLATE in the math class used story problems as the focal language. This text was shorter and had a different reading objective – identifying relevant information to solve a math problem. However, there was still significant linguistic and cultural content for students to decode.

In this lesson, the students were Nepali speakers from Bhutan, but like many refugee background students, they were not confident writing in Nepali. To have a written translation to review and discuss, the math teacher wrote an approximation of students’ language using English phonology (see Figure 4).

This group made vocabulary and register connections in English and Nepali, and they demonstrated high multi-cultural awareness when discussing translations for ‘pie’, which they did

not feel had a simple translation and needed to be culturally decoded. While this group of students did have rich language-focused conversations, they also ran out of time to solve the math equations, which led the math teacher to adjust the activity to include more culturally relevant prompts in her next lesson and ask students to only translate the last line of the problem to focus more explicitly on the math learning objectives. We see this as an excellent example of how translation can create an opportunity for students to use their multilingual repertoires to explore the language of mathematics including the kinds of culturally specific references that might appear on a standardized test. However, this example also makes clear that teachers must carefully design lessons to balance this important work with other math objectives.

Collaborative learning

After all the teachers tried TRANSLATE, the team debriefed together. Several learnings stand out as particularly important for other teachers interested in this activity.

- Start with content AND language objectives in mind. Translation with a focus on building teacher and student language awareness is a powerful opportunity to work toward content and language goals simultaneously. We found that being clear on both objectives helped us make effective decisions for text choice and how to allocate class time.

- Text choice makes a huge difference, but it is not easy to find an appropriate text! Productive texts for translation are relevant to students, connect clearly to content objectives, and create the “right” amount of struggle for students (typically with figurative language or complex structures that require collaboration and problem solving to translate).

- Translation takes time. After the first tryouts, it became clear that students needed more time to dig into this activity. Students were developing rich language awareness, but it takes time to go deep. It also takes some trial and error to adapt this activity into instruction in ways that are responsive to specific student groups. For example, teachers found that pre-teaching the text or allowing students to produce translation orally worked better with students with emergent literacy in their home language, whereas the written translation worked well for students with extensive formal schooling in their home language.

TRANSLATE as a unit focal activity

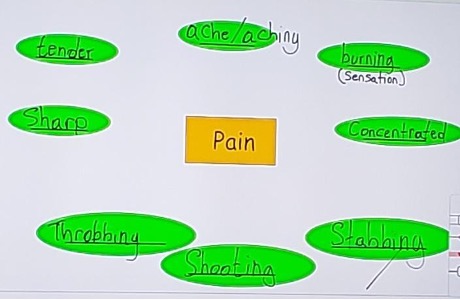

After the initial tryout, two teachers taught units using pedagogical translation as a focal activity. Their objectives and implementation differed, but both units leveraged students’ complex languaging practices to teach content and highlight students’ multilingual skills. The ELA instructor used personal and professional experiences to teach vocabulary for medical visits.

English language development class: Navigating medical visits

With a background as a medical interpreter and as a language broker for his family, the ELA teacher wanted to ensure that students could confidently navigate medical visits. For this unit, he identified vocabulary describing symptoms and types of pain. Based on his objectives, the research team created dialogues to be focal texts (see Figure 5).

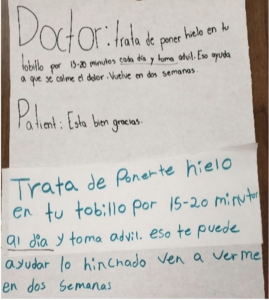

The ELA teacher invested in the idea of comparing translations while emphasizing that there are multiple correct ways to translate meaning. He created two groups of Spanish-speaking students who compared their translations. Because there were only two Arabic-speaking students in his class, the ELA teacher requested individual translations before asking them to compare notes. After reading several doctor-patient scripts, students translated (see Figure 6):

Doctor: Try putting ice on your ankle for 15 to 20 minutes a day and take Advil. They may help your swelling go down. Come back to see me in two weeks.

Patient: Ok, thank you.

Once the Arabic-speaking students translated, they compared work and noticed differences and similarities. For the Spanish groups, the ELA teacher displayed both Spanish translations for the class and elicited noticings from students.

Finally, the ELA teacher incorporated speaking and listening skills into an authentic context and asked students to role play a doctor-patient-interpreter interaction using their TRANSLATE scripts (see Figure 7).

Sheltered social studies: Learning the language of war

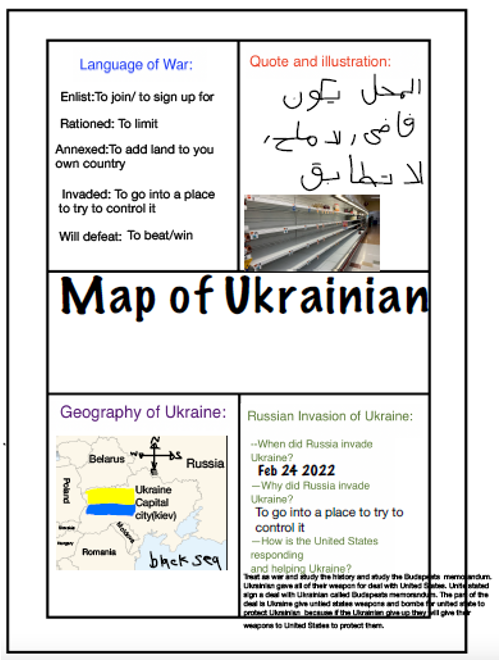

In contrast to the ELA teacher’s doctor-patient role play, Kelly Grucelski, the PLC Lead Teacher and a co-author on this article, used “The Language of War” as her social studies theme to connect with the war in Ukraine. Kelly wanted students to be able to share details about the Russian invasion of Ukraine while using unit vocabulary to highlight information they found particularly meaningful. The 11-day unit included contextualizing activities followed by specific language-building exercises.

NB: Activities in bold directly connect with pedagogical translation

Kelly used a multilingual poem from Ukrainian American educator and activist Ruslana Westerlund titled, Learning the Language of War. After reading this poem, students defined several words from their context in the poem. They also brainstormed their own words of war as a class, including vocabulary in any language.

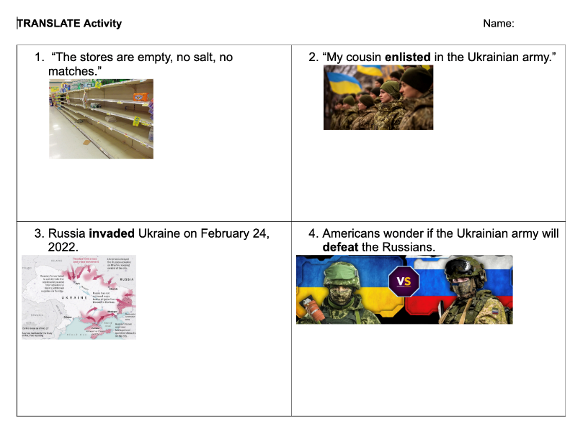

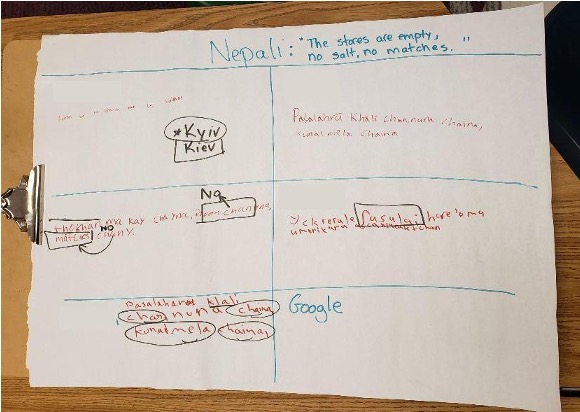

Next, while sitting in like-language groups, students translated focal sentences and compared meaning with peers (see Figure 8). Many of the same Nepali-speaking students from the math class were also in Kelly’s social studies class. They were again working in a small group of their Nepali-speaking peers, but this time, building confidence from their initial tryout, they decided to write their own translations.

After the Nepali-speaking students discussed and negotiated meaning, Kelly spent 10 minutes

learning about their language decision making. Most of the students who speak Nepali had chosen to translate the sentence: “The stores are empty, no salt, no matches.” (See Figure 9.)

The repetition of “no” in this sentence helped Kelly notice negation structure in Nepali. Unlike in English, the Nepali word to express negation, chaina, was placed after the words ‘salt’ and ‘matches’. Kelly was then able to highlight this difference and prompt students to articulate the grammar rule in Nepali (see Figure 10).

This was an ’aha’ moment for several students. The close comparison between what they knew about English and what they knew about Nepali enabled students to articulate connections about a specific language feature – negation – between two languages and build their metalinguistic awareness. This event shows how an attentive teacher can use simple questioning strategies to facilitate students’ developing language awareness.

After each student group spent time discussing their translations, they were invited to share their translations on the board. This further made visible the varied patterns of negation in students’ many languages. The summative assessment for this unit was a multilingual, summary one-pager (see Figure 11) where students showed the geography, vocabulary, and knowledge of world events that they had learned.

Creating ‘aha’ moments

For Kelly and the ELA teacher, building to the ‘aha’ moments was the result of many deliberate instructional and material choices. Long before they introduced their units of study, they went out of their way to elevate multilingualism and its benefits in their classrooms.

When planning their units, Kelly and the ELA teacher articulated learning outcomes based on upcoming content and chose or created level-appropriate texts with linguistic elements that would challenge students to think critically while using their full linguistic repertoires. For the ELA teacher, the texts featured key vocabulary for navigating medical visits. For Kelly, the text contextualized events in Ukraine, and the lines for translation included the repetition of a specific linguistic feature – “no salt, no matches.”

Beyond carefully setting up their classrooms as multilingual spaces, the ‘aha’ moments for the teachers also emerged from their sharp ability to notice language negotiation in action and ask critical questions of students. Kelly found herself relying on skills developed in her teacher training program when they were asked to notice things about languages such as morphemes or word order. She prioritized asking questions from a position of curiosity and playfulness. For example, when looking at student work in a language that she did not share, Kelly asked herself: What are some patterns that I am noticing? What stands out to me? What am I curious about that I have not seen before?

Kelly centered students by adopting the attitude of a learner and elevating students as experts. At times, students also went back to their parents or peers for answers, which underscored the deep cultural expertise of community members. At every stage, bringing this multilingual pedagogy to life as a teacher meant being willing to be in the process of learning and inquiry.

Multilingualism moving forward

TRANSLATE is just one of many ways to emphasize multilingualism as an asset in K–12 classrooms. Starting with small activities helped normalize classrooms as places that welcome all of students’ linguistic knowledge and practices. Then, asking students to draw on all their linguistic knowledge to make strategic choices about form and meaning helped increase awareness and make students’ metalinguistic processes clearer to themselves and others. By sharing our experience using pedagogical translation, we hope that other teachers will be similarly interested and inspired to share their current multilingual practices and try new ones.

Acknowledgement

This research was made possible in part by generous grants from the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs’ (CURA) Faculty Interactive Research Program and the Spencer Foundation (#201900075). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CURA or the Spencer Foundation.

References

García, O., & Kleifgen, J.A. (2019). Translanguaging and literacies. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(4), 553–571. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.286

Goodwin, A. & Jiménez, R. (2015). TRANSLATE: New strategic approaches for English learners. The Reading Teacher, 69(6), 621–625. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1400

Malakoff, M., & Hakuta, K. (1991). Translation skill and metalinguistic awareness in bilinguals. In E. Bialystok (Ed.), Language processing in bilingual children (pp.141–166). Cambridge University Press.

Appendix: Additional resources for teachers

- Translatetoread.com | Website for a reading curriculum designed around the TRANSLATE approach.

- Teaching Bilinguals (Even if you’re not one!) | Video series from CUNY.

- Global Story Books | Multilingual stories available online

- Tian, Z., & Shepard-Carey, L. (2020). (Re)imagining the future of translanguaging pedagogies in TESOL through teacher–researcher collaboration. TESOL Journal, 54(4), 1131–1143. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.614